A Cry of Defiance: Eight Essential Works By Yiddish Women Writers

David Mazower Recommends Miriam Karpilove, Chava Rosenfarb, Fradl Shtok and More

As a teenager in Austro-Hungarian Galicia, Yiddish writer Malka Lee confided in her poetry notebooks, keeping them hidden from her Hasidic father who viewed her scribbling as a sign his daughter was possessed by demons. Then, early one morning:

“…my mother rises to heat the stove, sets a match to the kindling, but it does not burn. She reaches into the oven door and far, far back, the flue is blocked with paper…my poems! My mother screams…I jump out of bed barefoot…I scream so hard that a clot of blood comes from my hoarse throat. I want to die…without my poems I no longer want to live. They lie torn, desecrated, and who has done this? My own father.”

Right there, Lee made the decision to leave home, “to go far, far away into the wide world.” It’s far from an isolated anecdote. Yiddish women’s writing as a body of modern literature emerged in the early twentieth century as a cry of defiance—against communal and family expectations, and in the face of a culture that prized men’s learning above that of women. Most Yiddish-language poems, stories, and novels by women are the hard-won fruit of such struggles. No surprise, then, that so much of their work is fearlessly modern, whether outspoken and rebellious or confessional and erotic.

Bringing this marginalized body of work to light has been a long labor of love. Most Yiddish literature, and especially that by women, was published in now-scarce journals, or on barely decipherable newsprint. Today, however, thanks to the work of scholar-translators like Frieda Forman, Jessica Kirzane, Irena Klepfisz, Goldie Morgentaler, Anita Norich, and Sheva Zucker, it is more accessible to English readers than ever. What follows is a forshpayz, an appetizer, to this rich and diverse body of work.

*

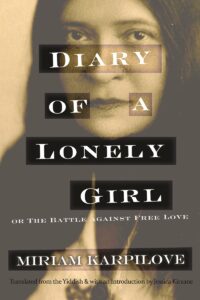

Miriam Karpilove, Diary of a Lonely Girl, or The Battle against Free Love

“A. came to my home yesterday. As he held me in his arms I felt small and lonesome. He didn’t come to bring me happiness; he only came to take some of it from me. No, that’s not quite right. He calculated carefully how much love he should give so that he wouldn’t owe me anything.”

Serialized in the New York Yiddish press in the 1910s, Karpilove’s knowing, fast-talking diary novel is a wry commentary on the courtship scene of New York’s Jewish immigrant milieu. Her narrator, an independent, single, sexually liberated woman, is alternately lovestruck and disillusioned. Against a backdrop of debates about free love, birth control, and radical politics, a parade of predatory and shallow men demand she submit to their advances. A romantic farce with a serious purpose, Karpilove’s freewheeling novel will feel instantly familiar to fans of Sex and the City and Bridget Jones’s Diary.

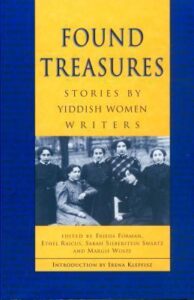

Found Treasures: Stories by Yiddish Women Writers, edited by Frieda Forman, Ethel Raicus, Sarah Silberstein Swartz

This pioneering anthology changed the direction of Yiddish studies, bringing to light previously untranslated short fiction and memoirs by eighteen Yiddish women writers. First published in 1994, it put down a marker for later translators: the authors featured are now significantly more widely available, and their multi-sided literary careers better understood. Most were immigrants from poor backgrounds, born in the Russian Empire between 1870 and 1910 and flung across the Atlantic as children or adolescents. Portrayals of girls and women in conditions of acute hardship or distress are a common theme of the collection. Rokhel Brokhes’s story The Zogerin (The Woman Prayer Sayer) is a miniature masterpiece of psychological disintegration. Gnesye, an aging grandmother, has spent her life at the gates of the shtetl cemetery. From the pennies given her by wealthy women to say prayers on their behalf, she scrapes a living for herself and her orphaned grandson. Tormented by thoughts of her poverty and her clients’ riches and finery, she finally snaps. In future, she screams to her terrified grandson, she will pray only for their misery and downfall.

The Mother of Yiddish Theater: Memoirs of Ester-Rokhl Kaminska (ed. and trans. Mikhl Yashinsky)

The modern Yiddish theater was conjured into being in barns and beer halls by Avrom Goldfaden, a yeshiva student turned impresario, in 1870s Romania. Orthodox Jews viewed the pop-up novelty with its mixed troupes as an abomination, but young female actors and singers embraced the emancipatory promise of the stage. If Goldfaden was the Yiddish theater’s self-described father, the Polish Jewish actress Ester-Rokhl Kaminska was acclaimed as di mame—the mother. A luminous presence on stage and off, she transcended a poor shtetl upbringing to define the early Yiddish art theater era. Available for the first time in English, her newly translated memoir charts her life from tsarist Russian childhood to full-blown global celebrity. It’s full of wonderful anecdotes, including the “orchestra” consisting of a woman French horn player who is also breastfeeding her baby, and the troupe that must muck out stables before admitting their audience.

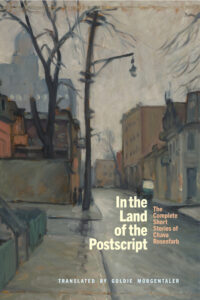

Chava Rosenfarb, In the Land of the Postscript: The Complete Short Stories of Chava Rosenfarb

Yiddish writers who survived the Holocaust and the murder of entire Yiddish-speaking populations had to deal with their own demons while confronting another set of tormenting questions: Who is there left to write for? Will anyone read my work? Should I try and write in another language? This burden weighed on Chava Rosenfarb, a young survivor of the Lodz Ghetto, Auschwitz and Bergen Belsen, yet she rose triumphantly above it. Settling in Montreal in her twenties, Rosenfarb wrote ceaselessly for her dwindling readership and is now recognized as one of Canada’s greatest writers. An established author of poems, novels and essays, she turned to the short story in her sixties and seventies, crafting these ten psychological portraits of Holocaust survivors building new lives in Canada and the United States. The longest story, and the best known, is “Edgia’s Revenge”—a searing tale in which two women survivors, united by a shared secret, meet unexpectedly in postwar Montreal.

Irena Klepfisz, Her Birth and Later Years: New and Collected Poems, 1971-2021

New Yiddish poetry is being written and published today in the US and UK, Israel, Russia, Poland, Canada, Austria, Germany, France, and elsewhere. Spoken word poetry rooted in traditions of oral entertainment is also alive and well in Hasidic communities, performed by Yiddish rhymesters of all ages. Within this contemporary Yiddish poetic landscape, Irena Klepfisz occupies a unique niche. A child survivor of the Holocaust and a trailblazing lesbian writer and American feminist, she writes at the intersection of Yiddish and English, the languages of her childhood and adult years. Her work in this comprehensive anthology braids politics, gender, history and memory into confiding and powerful lyrics. Reverberations and intimations are everywhere: cup your ear to Klepfisz’s ground and you hear echoes of the many overlooked Yiddish women writers and activists she has championed over the decades.

Fradl Shtok, From the Jewish Provinces

For decades Shtok was known as the great disappearing act of Yiddish literature—a modernist story writer who blazed bright in the 1920s before vanishing from the literary scene and, it was assumed, dying young. With this wonderful volume, translators Jordan Finkin and Allison Schachter have performed a double service. They have found poignant traces of Shtok’s final decades, a long silent coda ending in a New York psychiatric hospital. More importantly, they have recovered her sophisticated voice as a prose miniaturist. Whether set in Jewish eastern Europe or New York’s Lower East Side, Shtok’s range is on full display, from gossipy melodramas and elegiac reveries to coming of age portraits of shtetl adolescents and immigrant hustlers.

Puah Rakovsky, My Life as a Radical Jewish Woman

Written in Israel and first published in 1954 in Buenos Aires, this impassioned memoir describes Rakovsky’s self-made life as a radical activist, educator and leader in late-nineteenth and early-twentieth-century Poland. At the heart of her story is the revolutionary decade of the 1900s—an era of rising anti-Tsarist sentiment, which swept up a generation of Polish Jews, including Rakovsky, her children, and numerous friends. Among her vivid character sketches from that period is another Warsaw family, the Shapiros—father a school principal, mother “a village girl, a strong character and revolutionary spirit” and their four children. The whole family is deeply involved in the revolutionary movement: the oldest son disappears into Siberia, never to be seen or heard of again, while the youngest, eighteen, is jailed together with his father, and executed after his cell is exposed by an informer. The youngest daughter, Madzhe, is Rakovsky’s student. These few pages, earmarked in my copy, speak powerfully to me a century and more later. Why? Because Madzhe Shapiro is my great-grandmother and Rakovsky’s moving tribute is one of the earliest and most vivid family stories we possess.

Anna Margolin, Lower East Suicide

Yiddish literature is rich in great women poets including Celia Dropkin, Rokhl Korn, and Kadia Molodowsky, yet comprehensive collections of their work in translation are few and far between. Anna Margolin, a consummate modernist whose poems slide fluidly between genders, epochs, and literary traditions, has fared better than most. And yet, new facets of her work are still emerging. Most recently, Mildred Faintly has brought her own crystalline wordsmithing to the challenge of translating Margolin’s 1929 collection, her one published volume before she withdrew into self-willed silence. A transgender translator, Faintly is sharply attuned to Margolin’s gender ambiguity, asserting that “her lesbianism, unambiguously expressed in her poetry, has been primly and consistently overlooked.” No longer. In Faintly’s hands, Margolin’s hallucinatory lyrics emerge as sleek, chiseled and lyrical as a Brancusi sculpture. Lower East Suicide makes a compelling case for Anna Margolin to be considered a kindred spirit to Sylvia Plath, Marina Tsvetaeva, and Anne Sexton.

__________________________________

Yiddish: A Global Culture: Bold Lives, Boundless Creativity by David Mazower is available from White Goat Press.

David Mazower

David Mazower is the author most recently of Yiddish: A Global Culture: Bold Lives, Boundless Creativity (White Goat Press, 2025), a companion volume to the permanent exhibition of the same name at the Yiddish Book Center in Amherst, Massachusetts. The Center’s chief curator and editorial director, he is the author of Yiddish Theatre in London and has written widely on Jewish culture and the work of his great-grandfather, bestselling Yiddish writer Sholem Asch.