A Cross-Genre Trek: How Translation Improved My Debut Novel

Laura Venita Green Explores How Learning Italian Has Made Her English Writing Better

When I was thirty-eight years old, in late 2017, it began to feel inexcusable that I was living out my entire life in the typical American fashion: speaking a single language. After all, I spent six of my first eight years of life in Germany (on army bases). My father worked as a military linguist with a specialty in Mandarin Chinese and Russian. I’m a curious person who enjoys traveling and learning new things. When I made the decision to learn a new language, I chose Italian for a few reasons: I love visiting the country, my mom’s dad is Italian, and it’s a relatively easy language for English speakers to learn and pronounce.

Two years later, when I began an MFA at Columbia, I learned that if I took fifteen (of sixty) credit hours in translation classes, I could graduate with an MFA in both fiction and translation. Though I hadn’t progressed very far in teaching myself Italian, I’m motivated by deadlines and professor expectations, so I thought this would be a great move. I was not wrong. My original goal in translating was that I thought it would force me to learn Italian, but what really came of it was that it made me a much better fiction writer.

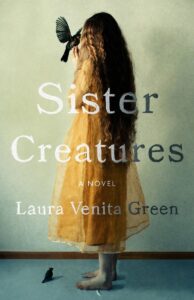

Without studying translation, my debut novel, Sister Creatures, either wouldn’t exist or would exist in a significantly less dynamic version. Here are four of the ways that my translation trek has improved my fiction writing:

There are countless approaches to choose from when telling a story.

This is delightfully illustrated in Raymond Queneau’s Exercises In Style, which tells the same short and simple story ninety-nine different ways. On the line level, there are countless word choice combinations to convey the same meaning (check out Reading Rilke by William Gass). I’m the type of fiction writer who gets caught up in my characters and their lives and actions. It wasn’t until I spent a significant amount of time translating, obsessing over every single word and sentence choice, trying out dozens before I settled on one, that I learned how to bring this level of precision to the use of language in my own fiction.

My protagonist feels similarly sheepish about her inability to master another language.

Here’s where I admit that, eight years later, I still can’t speak Italian. Though I can read (very slowly) and translate (very carefully), and though as of this writing I’m on a 1,879-day Duolingo streak (ha!), I’m far from fluent. I freeze like a deer in headlights if anyone actually tries to speak to me in Italian, my brain too slow, always lagging several words behind.

By reading other cultures widely, we can start to see that there truly are countless ways to tell a story.

My protagonist in Sister Creatures, Tess, who grew up in rural Louisiana just like me, is a self-destructive college dropout with an alcohol problem and a horror obsession. She meets a girl in the first chapter who ends up writing her a note in German. This kicks off in Tess a lifelong interest in the language. We see her attempting to learn German; we see her never quite getting there. She doesn’t admit it out loud, but I know her well, and I can tell that this inability embarrasses her. Though I suspect that, like me, Tess gets more out of the winding pursuit of a goal than she would out of the achievement itself.

Experiments in translation made it into my book.

Midway through Sister Creatures, Tess finally translates the German note she received in the first chapter. In order to make her first attempt sound sufficiently unpolished, I ended up writing the letter in English, translating it very clunkily into German, and then, after some time, re-translating it back to English. It ended up being the only way I could make it sound convincingly foreign. This wasn’t a very efficient method, but sometimes the least efficient method makes for the best art.

Additionally, later in the book, Tess moves with her family onto an army base in Garmisch, and she’s actively trying to learn, listening to German-language lessons on tape. In a late revision of this chapter, I added a bilingual element. Written in a close third-person point of view, it made sense that Tess was replacing English words with German. Plus, the addition makes the chapter more fun to read.

I read a lot of literature in translation now, and it has helped me move past U.S. norms and expectations.

Sister Creatures is a unique book, and that’s largely because of the increasing influence world literature has on my own writing. By U.S. standards, some of the translated books I love most could be seen as too messy, or too quiet. Too melodramatic or too dream-like. Lacking in resolution or over-explained. By reading other cultures widely, we can start to see that there truly are countless ways to tell a story. By studying structural and artistic choices of authors from various cultures, the potential for what is possible in fiction suddenly seems boundless.

__________________________________

Sister Creatures by Laura Venita Green is available via Unnamed Press.

Laura Venita Green

Laura Venita Green is a writer and translator with an MFA from Columbia University, where she was an undergraduate teaching fellow. Her fiction won the Story Foundation Prize, received two Pushcart Prize Special Mentions, was a finalist for the Missouri Review Jeffrey E. Smith Editors’ Prize and the Tennessee Williams & New Orleans Literary Festival Fiction Contest, and appears in Story, Joyland, The Missouri Review, and Fatal Flaw. Her translations appear in Asymptote, World Literature Today, Spazinclusi, and The Apple Valley Review. Raised in rural Louisiana, Laura now lives with her husband in New York City. Sister Creatures is her first novel.