A Compendium of Literary Ravens

Angus Hyland and Caroline Roberts Catalogue the Corvids of Aesop, Dickens, and More

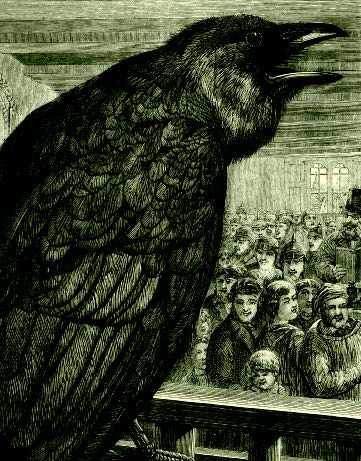

A Raven Called Grip

Charles Dickens’s beloved black bird

June Hunter, Raven Thought, Odin’s Advisor, 2016

June Hunter, Raven Thought, Odin’s Advisor, 2016

The Dickens household was quite the menagerie, with many dogs, cats and birds in residence, but the writer’s favorite companions were undoubtedly his pet ravens. Over the years, three ravens (all of whom were named Grip) lived at 1 Devonshire Terrace in Marylebone, London. The various Grips ruled the roost, pecking Dickens’s children, terrorizing the various dogs and stealing their food.

Dickens was devoted to his corvid companions and featured a raven called Grip in his fifth novel, Barnaby Rudge. The real and fictional Grips bore several similar traits, including their cheeky greetings and blatant disregard for manners. According to the young Eleanor Smithson, who was visiting at the time, Grip “greeted me with ‘Halloa, old girl!’, made some alarming pecks at my ankles and altogether was unpleasantly familiar.” In Barnaby Rudge, our hero is described as a simpleton and Grip is his constant companion, accompanying him when he’s thrown into Newgate prison.

Not everyone took such a dislike to Grip, however. In 1842 the real Grip accompanied Dickens on a trip to the United States and, while in Philadelphia, they met the American writer Edgar Allan Poe, who was rather taken with Dickens’s chatty corvid companion—so much so that it is widely thought he was the inspiration for Poe’s famous poem The Raven. When Grip III passed away, Dickens had him stuffed and kept him above his desk. After Dickens died, thanks to various collectors, Grip travelled to the United States several more times, and he now proudly resides in the Free Library of Philadelphia.

*

Fairytale Endings

The ravens of the Brothers Grimm

Like the best fairytales, The Seven Ravens has all the right ingredients: intrigue, long-lost family, a dwarf, a bit of grisliness and of course the obligatory happy ending. Tale number 25 (of a total of 211 written by the prolific Brothers Grimm) is type 451 in the Aarne–Thompson folklore classification (which lists all the tales that involve sets of brothers turning into birds).

The story begins with an old couple who have seven sons. They almost give up hope of having a daughter, but she finally arrives, albeit rather frail and sickly. The couple decided to baptize her, and her father sends her seven brothers to a well to fetch water. In all the excitement, they drop the water jug into the well, and when they haven’t returned for some considerable time, the father curses them and wishes they were turned into ravens. This duly happens, and to cut a long fairytale short, the girl grows up, hears about her brothers and goes off in search of them. The journey involves a meeting with a dwarf, a glass mountain and the girl chopping off part of her own finger, but it ends happily with the brothers regaining their human form and everyone being reunited (if a little lacking in the digit department).

The moral of this tale? Be careful what you wish for, because you might just get it. Jugs can be slippery when wet. Oh, and self-amputation is best left for fairytales…

*

Crow-haunted & Death-involved

Hughes and Baskin’s shared obsession

First published by Faber and Faber in 1970, Crow: From the Life and Songs of the Crow is considered to be one of Ted Hughes’s most important and controversial works. Described by the poet as his “masterpiece,” the book was written in the years following the death of his wife, Sylvia Plath. It was not considered by Hughes to be finished work when it was first published, and he added further poems to two later editions (in 1972 and 1973). It was for Hughes a very creative period that both started and ended in tragedy—six years after Plath committed suicide, his mistress Assia Wevill did the same, also killing their child Shura.

The poem was described by Hughes at the time as using “supersimple, super-ugly language.” It explores themes of sex, religion and death, and the protagonist is based on the Trickster—a disruptive and often elusive character who appears in many primitive mythologies. Hughes was inspired by his friend Leonard Baskin’s drawings of crows, and the cover of the first edition featured one of his works. Hughes insisted that compared to Baskin’s striking illustrations, “my poor text wilts.” The pair had struck up a firm friendship, and Baskin even moved his family from his native United States to Devon to be nearer to Hughes. Despite coming from very different backgrounds, Baskin eloquently (and probably accurately) described the pair as being “crow-haunted and death-involved.”

*

Curiouser & Curiouser

Mad Hatter: ‘Why is a raven like a writing-desk?’

‘Have you guessed the riddle yet?’ the Hatter said, turning to

Alice again. ‘No, I give it up,’ Alice replied: ‘What’s the answer?’

‘I haven’t the slightest idea,’ said the Hatter.

–Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

Kathryn LeMieux, Flora’s Ravens, 2011

Kathryn LeMieux, Flora’s Ravens, 2011

In Lewis Carroll’s novel, the seven-year-old Alice is introduced at a tea party to a character who has come to be known as the Mad Hatter. Carroll never actually referred to the Hatter as “Mad,” but the top-hat-wearing character’s penchant for cutting remarks, nonsensical poetry and rhymes that were impossible to answer probably contributed to this name sticking.

One of the conundrums the Hatter put to Alice was: “Why is a raven like a writing desk?”, but when prompted, he couldn’t provide the answer. After being badgered by readers over the years to reveal the answer, Carroll included a response in the preface of a later edition: “Because it can produce a few notes, tho they are very flat; and it is never put with the wrong end in front!”

Like a good deal of the Hatter’s own ramblings, Carroll’s explanation didn’t make an awful lot of sense. In 1991 The Spectator held a competition to solve the mystery, and winning entries included “because a writing desk is a rest for pens and a raven is a pest for wrens”; but this was not what Carroll had intended. Unfortunately, just before the book went to press, the well-meaning proofreader had changed the word “nevar” (which is raven spelled backwards) in Carroll’s preface to the word “never,” thus completely killing what wasn’t a very funny joke in the first place.

*

Telling Tales

Aesop’s fables

The Greek storyteller Aesop lived from 620 to 564 BC, and although none of his fables was written down at the time, his much-loved tales have been passed on by word of mouth to the present day. There are 725 fables attributed to Aesop, and many feature animals with human traits. The Fox and the Crow is fable number 124, a cautionary tale that involves a piece of cheese and the perils of listening to flattery.

It’s a simple story in which a crow finds a piece of cheese and hops up on to a branch to eat it. The fox decides that he’d quite like the cheese, so he flatters the crow, telling him how beautiful he is and wondering whether his voice is just as sweet. The crow starts to sing, and drops the cheese, which is promptly devoured by the fox.The moral? Don’t fall prey to flattery, especially if it comes from the mouth of a cunning fox. The Fox and the Crow was hugely popular in France, and was the first featured in Jean de La Fontaine’s classic collection of fables, which were published between 1668 and 1694. Since then, many generations of French children have learned it by heart.The fable has been interpreted in many forms including music, dance and sculpture (a fox and a crow feature in La Fontaine’s statue in Paris). It’s even depicted three times in the Bayeux Tapestry, as well as further afield on Paul Manship’s Osborn Gates in Central Park, New York.

*

Enter Stage Left

The Upstart Crow’s favorite corvids

Yes, trust them not, for there is an upstart crow, beautified with our feathers, that, with his Tygers heart wrapt in a Players hide, supposes he is as well able to bumbast out a blanke verse as the bestof you; and being an absolute Johannes Factotum, is in his owne conceit the onely Shake-scene in a countrie.

In what was clearly a bad case of professional jealousy mixed with a dose of good old-fashioned snobbery, the playwright and Oxbridge literary scholar Robert Greene certainly had the knives out for William Shakespeare. Not content with badmouthing him to all and sundry, he went to the trouble of printing a leaflet in which he called into question the Bard’s credentials asa writer and accused him of being an ‘upstart crow’ with ideas above his station. Shakespeare went on to use the symbolism of both crows and ravens as harbingers of doom to great effect in many of his plays.

In Macbeth, Lady Macbeth tells us how the raven predicts the king’s murder:

The raven himself is hoarse

That croaks the fatal entrance of Duncan

Under my battlements.

During the play scene in Hamlet, ravens are used to symbolize the Prince’s desire for revenge on his stepfather:

Begin, murderer. Pox, leave thy damnable faces, and begin!

Come, the croaking raven doth bellow for revenge.

There is a theory that Shakespeare exacted his revenge on Greene by modeling one of his most notorious comic characters on him. Appearing on stage in Henry IV Part One and Part Two, and in Henry V, Sir John Falstaff is described as being a not-very-charming combination of overweight, boastful, lazy, corrupt, thieving, manipulative and lecherous.

______________________________________________________________

Excerpted from The Book of the Raven: Corvids in Art and Legend by Angus Hyland and Caroline Roberts. Copyright © 2021 by Angus Hyland and Caroline Roberts. Excerpted by permission of Laurence King Publishing Ltd.. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Angus Hyland and Caroline Roberts

Angus Hyland is a graduate of the Royal College of Art and a partner at Pentagram Design London. His previous books include Hand to Eye, The Picture Book, Symbol and The Purple Book. Caroline Roberts is a journalist and author who writes mainly about the graphic arts, and she was the founder of Grafik magazine.