A Close Reading of the Best Short Story Ever Written

From Your Resident Donald Barthelme Stan

I was introduced to Donald Barthelme in college, in a writing workshop with the novelist Robert Cohen. We read “City of Churches” and “The School,” and for a week or so afterwards, I walked around in alternating states of elation and depression. On the one hand, after what seemed (at the time) like a long lifetime full of reading, I had suddenly found something I had never seen before. These stories seemed like magic; they tugged on the throat and stomach, while also being funny, while also arching a brow, by which I mean to say they were (and are) my perfect emotional cocktail. On the other hand, I despaired, because obviously I was never going to be a writer, because obviously I could never do what Barthleme had done, holy shit, how had he done this, I had better throw in the towel now!

While I would eventually read most of Barthelme’s stories, “City of Churches” and “The School” are still my favorites. And also “Rebecca,” which I would find later. “Rebecca” is incredible. You need “Rebecca” in your life. Go now, to “Rebecca.” I say all of this up front as a way of admitting something you and I both know anyway: that literary taste is subjective, and related to one’s experiences, particular proclivities, and personal interests, and that no one short story can actually be deemed by any reliable metric to be objectively the Best. I understand this fully. Still: this story is the best short story. I say this because I know it to be true. You may have your own best short story. But here is why “The School” is mine.

“The School” was originally published in The New Yorker on June 17, 1974. It is very brief, just over 1,200 words, which is rare for a story this affecting, but not particularly rare for Barthelme. The format is instantly recognizable: it’s an escalation story. If you’ve been in an introductory workshop (certainly one taught by me) you’ve heard of those. Something bad happens; something worse happens; something even worse than that happens next. This is also the format of many jokes. In his essay “Rise, Baby, Rise!“, George Saunders places it “roughly in a lineage of ‘pattern stories,'” including Chekhov’s “The Darling,” Gogol’s “Dead Souls,” and “A Christmas Carol.” In this case the thing that happens—the pattern—is that things at the narrator’s school die.

The story begins like this:

Well, we had all these children out planting trees, see, because we figured that . . . that was part of their education, to see how, you know, the root systems . . . and also the sense of responsibility, taking care of things, being individually responsible. You know what I mean. And the trees all died. They were orange trees. I don’t know why they died, they just died. Something wrong with the soil possibly or maybe the stuff we got from the nursery wasn’t the best. We complained about it. So we’ve got thirty kids there, each kid had his or her own little tree to plant and we’ve got these thirty dead trees. All these kids looking at these little brown sticks, it was depressing.

Immediately, with no set up, we are dropped into a distinctive but recognizable first person tone: our narrator is trailing off, he is nervous, maybe, likely he is apologetic, and certainly he is telling a story. He’s telling it directly to me, the reader—in the next paragraph he’ll say, casually, “you remember,” as if I live in the world he lives in. That world is the world of the school—we know this from the title, though we’re not told this explicitly in the first paragraph. We intuit that it’s the teacher speaking to us: “we had all these children,” etc., though we are not told this explicitly either. We are also, of course, introduced to the notion of things dying. The fact that it’s orange trees in this first paragraph probably means nothing. Maybe we’re in California, or possibly Florida—actually this does seem like the kind of story that would take place in Florida, because everyone knows that’s where the weirdest shit happens, so Florida it is. According to the online Symbolism Wiki (this exists) the orange tree is a symbol of generosity and wisdom and sometimes purity. (Take this with a grain of salt, of course, for all the usual reasons and because there is a misspelling in this entry.) Even if true, I doubt Barthelme was thinking of the symbolism. Orange trees are kind of lovely, and kind of odd, and the kind of things kids in Florida would probably want to plant. More specific than generic trees, and sweeter. That is enough, I think.

Anyway, next we are told that all the snakes have also died (what kind of school has multiple snakes, I wonder?), but that this was understandable because of the strike. The strike, which is never mentioned again, gives us just a small hint of turmoil in the world outside the school. I’ve always found the strike tantalizing; it could be an indication that the events in this story are a symptom of some grander scheme—even if only a impressionistic, and not a direct, symptom. It could just be a little color, a way to explain away the snake deaths. Either way, it seems unlikely that the snakes would die after only four days. They are usually pretty resilient.

Then we hear about the herb gardens, which have either been overwatered or sabotaged, and then, as if in afterthought, we are reminded about the gerbils, mice, and the salamander, who have also died this year. All of this is still in retrospect, a retelling. Then of course we have the tropical fish, and the gentle suggestion that what we’re looking at is a pattern that repeats, or has repeated, that it is not this class, this year, but all classes, all years:

Of course we expected the tropical fish to die, that was no surprise. Those numbers, you look at them crooked and they’re belly-up on the surface. But the lesson plan called for a tropical fish input at that point, there was nothing we could do, it happens every year, you just have to hurry past it.

We weren’t even supposed to have a puppy.

How chilling is that sentence, all alone as its own paragraph! We’ve been waiting around for the deaths to stop being funny, to start getting serious, and this is where it starts, with that ominous single line. You know what’s coming. You know it with dread and with excited anticipation, because how will this one die? In order to stave off what might be the increased sadness in the reader, on the scale of herbs to fish to puppy, Barthelme infuses the puppy with some real delight.

They named it Edgar—that is, they named it after me. They had a lot of fun running after it and yelling, “Here, Edgar! Nice Edgar!” Then they’d laugh like hell. They enjoyed the ambiguity. I enjoyed it myself. I don’t mind being kidded. They made a little house for it in the supply closet and all that. I don’t know what it died of. Distemper, I guess.

I actually cannot fully unpack why I so ardently love “Distemper, I guess.” I just love it. I would tattoo it on my body were I not too afraid of pain to even have my ears pierced. Apparently distemper is a real viral disease in dogs (and cats, and seals, and skunks, and pandas, and a variety of other animals) and is also known as hardpad disease. According to Wikipedia, in dogs, “signs of distemper vary widely from no signs, to mild respiratory signs indistinguishable from kennel cough, to severe pneumonia with vomiting, bloody diarrhea, and death.” It is in the same family of viruses that causes measles and mumps. I did not know any of this until this very moment. I have always read the word as an antiquated way to say “ill temper” or, more to the point, “unhappiness.” Despite the fact that I am technically wrong, I still think this meaning lives, submerged, in the word, and adds to its official meaning. We all enjoy ambiguity. Everyone in this story suffers from a sort of distemper. As for the “I guess,” well, that’s just more of this narrator’s sad sack waffling, which by now we have all grown to love, have we not?

Well. On to the Korean orphan. Oh god, you think. But even still, the Korean orphan is far away, much farther than the children’s parents.

We had an extraordinary number of parents passing away, for instance. There were I think two heart attacks and two suicides, one drowning, and four killed together in a car accident. One stroke. And we had the usual heavy mortality rate among the grandparents, or maybe it was heavier this year, it seemed so. And finally the tragedy.

We know, of course, what this must be.

The tragedy occurred when Matthew Wein and Tony Mavrogordo were playing over where they’re excavating for the new federal office building. There were all these big wooden beams stacked, you know, at the edge of the excavation. There’s a court case coming out of that, the parents are claiming that the beams were poorly stacked. I don’t know what’s true and what’s not. It’s been a strange year.

After this diffuse and reflective—and actually quite sad—moment, Barthelme backtracks to say:

I forgot to mention Billy Brandt’s father who was knifed fatally when he grappled with a masked intruder in his home.

I can only marvel here, as he has somehow made the fatal knifing of the father of a young boy a laugh line. I mean, I laughed. Not only that, but this slight backtracking has provided space for the hinge in the story—we’ve been moving forward, with slight asides, the whole time, but now we have taken a breath. So, slight backtrack, and then the hinge, which allows us to slide into the conclusion:

One day, we had a discussion in class. They asked me, where did they go? The trees, the salamander, the tropical fish, Edgar, the poppas and mommas, Matthew and Tony, where did they go? And I said, I don’t know, I don’t know. And they said, who knows? and I said, nobody knows. And they said, is death that which gives meaning to life? And I said no, life is that which gives meaning to life. Then they said, but isn’t death, considered as a fundamental datum, the means by which the taken-for-granted mundanity of the everyday may be transcended in the direction of—

I said, yes, maybe.

They said, we don’t like it.

I said, that’s sound.

They said, it’s a bloody shame!

I said, it is.

The “where did they go” is of course heartbreaking because, well, don’t we all want to know the answer? But the way the students, who given all their pets we can only imagine to be elementary-age, transition into this elevated discourse, is Barthelme’s deftest move yet. Rules about common behavior are now irrelevant, as if they weren’t already. We are plunged into an entirely new mode. We are ready for it, of course; we’ve been prepared by all the surreality, to the point where it almost makes sense for ten-year-olds to use the phrase “fundamental datum.” I find this moment ecstatic—it is literally transporting, pulling you up out of the pattern and making you look around. It is as if we have passed through a door.

They said, will you make love now with Helen (our teaching assistant) so that we can see how it is done? We know you like Helen.

I do like Helen but I said that I would not.

We’ve heard so much about it, they said, but we’ve never seen it.

I said I would be fired and that it was never, or almost never, done as a demonstration. Helen looked out the window.

They said, please, please make love with Helen, we require an assertion of value, we are frightened.

After all, what could be said to be the opposite of death but sex, and that which it produces? It makes emotional sense but not logical sense—even though, as Saunders points out in his aforementioned essay, there was no Helen until she was conjured here, in the fourth-to-last paragraph. “The reader (this reader anyway) falls, once and for all, forever, in love with this story, at the line: ‘Helen looked out the window.’” Because in one ambiguous moment it is clear that the newly-formed Helen has not only been there the whole time but loved the narrator, the teacher, who has, you only notice now (or at least I only notice now) managed to shake off his ellipses and dithering and tell it to us straight, now that Helen is on the line. But in fact, there have been no ellipses since we transitioned into recounting the deaths of humans. Even our narrator can pull it together when necessary. One of Barthelme’s great skills, in this story and in others, particularly the others I have mentioned, is to play around and play around and play around and conjure delight and conjure strangeness and then right when you’re all woozy and giggly and your ankles are exposed—nail you with some plainspoken emotional resonance.

I said that they shouldn’t be frightened (although I am often frightened) and that there was value everywhere. Helen came and embraced me. I kissed her a few times on the brow. We held each other. The children were excited. Then there was a knock on the door, I opened the door, and the new gerbil walked in. The children cheered wildly.

Okay, wait. Who has knocked? Was it the gerbil? Was this how all of the other doomed creatures entered as well? Is this the key to their deaths? Or—has this gerbil been reincarnated? We heard about some dead gerbils earlier. Or, have the children, cheering, interpreted the new gerbil as the product of their teacher embracing Helen? It doesn’t matter. I don’t need to know. It is perfect in its obscurity. The story has already done its work—it has created a feeling in the reader. I will quote, as many have, Bret Anthony Johnston’s “Don’t Write What You Know,” in which he argues: “Stories aren’t about things. Stories are things. Stories aren’t about actions. Stories are, unto themselves, actions.” The point of a story is to change things, to do something. For this reader, this one does something every time.

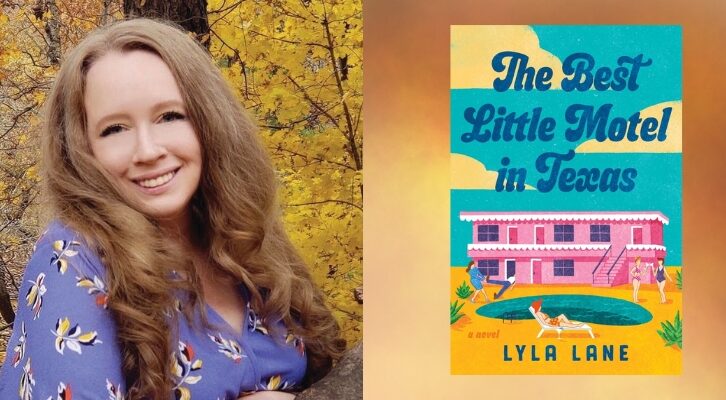

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.