A Close Reading of Edna St. Vincent Millay’s “Counting-Out Rhyme”

Cecily Parks on the Ceremony and Intimacy of a Classic American Poem

Descriptions of tree bark and heartwood, arranged into lines that rhyme: that’s Edna St. Vincent Millay’s “Counting-Out Rhyme.” There’s no first-person “I” inside the poem to act as a reader’s avatar, no ticking-time-bomb of a first line like “My candle burns at both ends,” which starts Millay’s oft-quoted poem “First Fig.”

However, over the course of four stanzas, something ceremonial and vitally intimate transpires. The simple act of counting and naming the trees in a particular landscape becomes rigorous and potentially revelatory. This is the first stanza:

Silver bark of beech, and sallow

Bark of yellow birch and yellow

Twig of willow.

Over the subsequent three stanzas, Millay’s poem summons a forest: beech, birch, willow, oak, hornbeam, and elder. Not simply naming trees, the poem also calls trees by the regional names they sometimes go by: “popple,” another name for poplar, and “moosewood maple,” another name for striped maple, whose bark moose forage on in the winter. Only a poem intimate with them would refer to trees this way:

Stripe of green in moosewood maple,

Color seen in leaf of apple

Bark of popple.

The poem’s stumbling, falling rhythm elides the lofty bounce or micronarrative of a nursery rhyme in favor of a tone that’s defiantly level, even procedural. Moreover, “Counting-Out Rhyme” does something different than the counting-out rhyme many of us first encounter in childhood, “Eeny, meeny, miny, moe,” by not exiling a child from a group, assigning her an objectionable task, and turning her into an “it” for the span of a game.

Only a poem intimate with them would refer to trees this way.

Though I haven’t found it in a children’s poetry anthology yet, the poem does the educational work that so many children’s poems do, gathering its subjects into a device of sound and meaning that secures our attention to them. If “Eeny meeny,” helps us navigate responsibility to a group, then Millay’s poem helps us navigate responsibility to a community that includes its ecosystem of more-than-human parts, especially those we cut down to make, in the following stanza, human tools such as a yoke or a barn:

Wood of popple pale as moonbeam,

Wood of oak for yoke and barn-beam,

Wood of hornbeam.

“What’s the environmental news here?” the scholar John Felstiner asked about this poem in his book about poetry’s power to reestablish our relationship to the environment before it’s beyond repair. He’s riffing on that William Carlos Williams passage: “It is difficult / to get the news from poems / yet men die miserably every day/ for lack / of what is found there.”

However, Felstiner falls short of making the argument that the poem serves as a primer for those who care for the earth and the language that describes it. The poem might also be a safe-deposit box, keeping the names of species intact for an environmentally unstable future, when the trees that the poem names may only exist in language.

But the language for the nature is endangered too, as scholar Robert MacFarlane noted at the turn of this century, when he discovered that the words for plants and animals had been removed from the Oxford Junior Dictionary to make room for entries like “blog,” “chatroom,” and “celebrity.” Those new words glow with the artificial light of the screens illuminating our days and nights.

The poem might also be a safe-deposit box, keeping the names of species intact for an environmentally unstable future, when the trees that the poem names may only exist in language.

Now that the night sky and the nocturnal lives that depend on it need to be safeguarded by Dark Sky initiatives, the poem “Dream Song” by Walter de la Mare, which names types of naturally occurring light, holds precious cargo: “sunlight,” “starlight,” “[e]lf-light, bat-light, / Touchwood-light and toad-light[.]” The poem finds a companion in Anne Carson’s “Every Day Unexpected Salvation (John Cage),” which collects types of shade.

Counting and accounting, these poems are both artifacts of environmental engagement and invitations to off-the-page environmental action. Take Millay’s poem to a forest and read it out loud, letting it guide your finger to point at all the trees it names. Maybe what you are doing will feel like a summoning, a gathering.

Not sure what the names of the trees are? Now is an excellent time to learn. Do different trees or plants grow where you live? Now is an excellent time to write a counting-out rhyme about them, planting them in one of the most powerful types of poems I know. All you need to do is notice what’s around you.

Silver bark of beech, and hollow

Stem of elder, tall and yellow

Twig of willow.

__________________________________

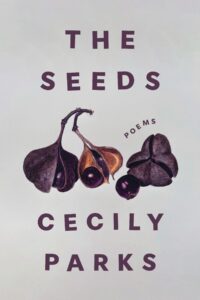

The Seeds by Cecily Park is available from Alice James Books.

Cecily Parks

Cecily Parks is the author of the poetry collections Field Folly Snow and O'Nights and editor of the anthology The Echoing Green: Poems of Fields, Meadows, and Grasses. Her poems appear or are forthcoming in The New Yorker, A Public Space, The New Republic, and Best American Poetry 2022. She teaches in the MFA Program at Texas State University and lives in Austin.