A City of Dreams and Dreamers: Ella Berman on Writing About Los Angeles

“There is no doubt that if anyone is capable of rebuilding and renewing, it is Los Angeles.”

At my family’s apartment in Los Angeles, there was a swimming pool that overlooked a tributary of the Los Angeles River called the Tujunga Wash. In the summer it was barren, an empty expanse of concrete, but sometimes, after a storm, a murky stream would thread through it and join the river near Studio City. I barely noticed this backdrop to my summers until a schoolfriend from London came to stay for a few weeks and asked about it. I told her it was a stream that fed into the river that fed into the ocean, and she drily suggested we’d been lied to by our realtor. Later, she suggested we drive up the winding canyons that separate the valley from the rest of LA to look at the mansions lining the hills. I hadn’t yet learned to covet homes like jewels (or the Tiffany necklace she wore) and, until then, had seen our apartment as only a haven.

In recent years, I have often felt ashamed of my love for Los Angeles. In certain circles, identifying with the city is shorthand for being uncultured and self-obsessed, even soulless. Occasionally, I have agreed—I watched Prince William marry Kate Middleton at 4 AM in the penthouse of a coked-up Hollywood heir. Once, I was asked to invite some ‘hot girls’ to dinner to please a producer who was double my age. Another time, I had to walk seven blocks to find a loaf of bread.

I wonder if, rather than a mirage, the city is a mirror. It can be the loneliest place in the world or the most thrilling, depending on your state of mind.

When I was young, my experience of Los Angeles was a suburban fever dream. As toddlers, my sister and I had drawn on the walls of our 1950s bungalow before my dad’s job brought us back to London. Even after we moved away, my family would spend every vacation in a two-bedroom apartment in a building in Sherman Oaks that lovingly smelt of borscht. We lived opposite a pianist who would play for thirteen hours a day, the tangled melodies unravelling across the hallway from the moment we woke to the moment we went to sleep.

My London life was filled with biology homework and birthday parties in the rain and jasmine tea with my grandma at her favorite dim sum restaurant. In the L.A. portion of my double life, the days were expansive and ripe. My sister and I spent most of our time in the pool (heading inside only to grab the occasional glass of Martinelli’s, our eyes stinging with sunscreen) or listening to KROQ as we sat in traffic on the 101, or eating Twizzlers at Cross Creek in Malibu with Sun-In in our hair, or choosing movies with our parents at Blockbuster, or hanging out at one our summer friends’ houses. Once, one of these friends casually mentioned they couldn’t remember the last time they’d used the pool in their own backyard and I stared at the water, trying to imagine it ever becoming ordinary; something you could outgrow like the Sweet Valley Twins books languishing at the bottom of my closet.

In my early twenties, I had a boyfriend who was an aspiring actor and I learned that, in L.A., even restaurant tables had an assigned value. I learned that a body type wasn’t something you were born with but was something that could be achieved by discipline and abstinence, and to accept otherwise was a moral failure. I met new friends with vast dreams but no heart in hotels with sharp angles but no soul. I was almost always hungry. I began to understand why everyone outside of Los Angeles found it to be a lonely place. I felt myself pull away, becoming one of the people who denounced its value. It wasn’t a wasteland to me, exactly, but something darker, more volatile.

I kept my distance for a while. I settled into life in London free from the persistent yearning I’d previously felt down to my bones. When I returned it was alone, on a research trip for my first book. It was the only place I would set my story of a jaded young woman sifting through the rubble of a life she’d once dreamed about. I was tentative at first, recording voice-notes as I drove down PCH as if it were my first time in the city. In one of them, in an uncertain voice accompanied by the thrashing ocean, I wonder if, rather than a mirage, the city is a mirror. It can be the loneliest place in the world or the most thrilling, depending on your state of mind.

When we lived in LA, my parents had a friend called Pat Warner. Pat was almost an L.A. native—she had lived in Hollywood since the late 1950s and could remember something that happened sixty years ago in more detail than I can remember last summer. She was constantly arguing with the Chateau Marmont management over their valet system—they would park the cars of the rich and famous outside her mid-century bungalow on Hollywood Blvd, effectively blocking the street.

Every day, Pat would drive her two-seater Mercedes Benz down to Sunset, and would eat at one of the many restaurants that used to be someplace else. She ate lunch alone or with friends, and somehow existed both firmly in the present and all the ghost versions of her beloved city. She taught me many things, but most of all that there is nowhere better than Los Angeles at preserving its own history. You can order the Chicken Parmigiana at Dan Tana’s and have almost the same experience as you would have in 1965, if you can only remember to put your phone down for a moment.

There is something about its unique vulnerability to natural disasters that reflects its intrinsic sense of impermanence and optimism. It is, at its heart, a city for hopeful people.

There is culture all over L.A. once you know where to look for it. There is culture in the salsa at Casa Vega and the martinis at Musso and Frank, and even in the pink cracked Walk of Fame stars that are nearly illegible; in the smell of hot dogs at Dodger Stadium and in the gardens of The Huntington Library, and the Canyon Country Store immortalized by The Doors, and in the Brentwood bungalow in which Marilyn Monroe lived and died. There is culture in the peeling art deco apartment buildings in Hollywood and the bustling flower market in downtown at 5 AM, and the Black Cat Tavern on Sunset which staged LGBTQ demonstrations against police brutality in 1967.

There is culture in the extraordinary Korean Festival held every October and in the Shades of LA collection at the LA Central Library, and in the unexpected angles of Lautner’s Sheats-Goldstein house and the iconic curve of Gesner’s Malibu wave house. And there is immeasurable culture and community in the thousands of activists currently protesting the inhumane ICE policies across the city, the humans being ripped from their own homes as if their lives are somehow worth less than their neighbors’, as if they belong any less to a city that was built for dreamers.

When the fires tore across the city earlier this year, I watched from London with a thudding sense of dread that turned into awe as Angelenos pulled together to provide relief for the families and entire communities who had lost everything. And there is no doubt that if anyone is capable of rebuilding and renewing, it is Los Angeles. Willed into existence by a dream rather than nature, there is something about its unique vulnerability to natural disasters that reflects its intrinsic sense of impermanence and optimism. It is, at its heart, a city for hopeful people. In a certain light, this sense of hope can feel like a tragedy. In another, even the Tujunga Wash can look like a ribbon of gold.

__________________________________

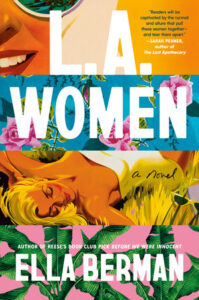

L.A. Women by Ella Berman is available from Berkley, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Ella Berman

Ella Berman grew up in both Los Angeles and London, where she studied psychology before working at Sony Music. Her debut novel, The Comeback, was selected as a Read with Jenna book club pick, and her follow-up, Before We Were Innocent, was a Reese’s Book Club pick. Raised by two former hippies on the music and art of the 1960s and ’70s, she lives in London with her husband, their senior dog, and their daughter.