A Chef Traces the Start of Her Career to Her Mother's Childhood

Iliana Regan on the Love and Comfort of Food in a Cold World

A long time ago, as I sat on the top stair to our barn attic and marveled at all the restaurant furniture covered in years of dust, I saw everything I needed to see to know exactly what it was like. At Jenny’s, I learned how to make pierogi through osmosis. I also learned how to quit something when I didn’t like it.

I began my career at Jenny’s Café.

Jenny’s had closed before I was born, but I could see the dark wood-paneled walls and the light cast from thick, rust-colored fixtures over the tables. I saw the steelworkers, eating bowls of borscht, and sauerkraut and sausage on thick enamel plates, becoming heated behind their beer bottles and ranting about union dues. I saw my sisters there, in their Catholic schoolgirl uniforms, studying, restlessly shifting, poking at one another as the night grew on. I saw my grandfather kiss my grandmother next to the bar. I saw my uncle Georgie, bouncing like a pinball between the tables as he drunkenly searched for the vodka bottle, hidden from him the night before. I saw my father bringing in a basket of green beans, corn, tomatoes, and zucchini from his garden. I saw him passing it to my mother through the kitchen window; I saw her smiling back at him. Sometimes, she really did love him.

Jenny is my dad’s mother. My mom doesn’t like her.

Jenny had five sons, and all five sons had wives. After my grandfather George died, Jenny couch-surfed, which created drama in her children’s lives. Her daughters-in-law, all five of them, told one another of Jenny’s mussings, about what she thought of the others. They gossiped, but she was mean to them. They felt it was within their rights to let each other know her thoughts. Combined, the wives were like The Witches of Eastwick. Then Jenny ended up in a tiny apartment in Hobart, Indiana.

*

My mom says I was an accident. She says we were all accidents. The first three accidents were all within four years. I came 13 years after the last one. She says she found out she was pregnant with me after a night of heavy drinking, and when the doctor told her, she cried. He thought they were tears of joy, because that’s how women were supposed to feel, but hers were more from helplessness, mixed with rage. By then, she had already built the case against my father. He was neglectful, mean-spirited, weak. He did his best to keep her dependent for years. He also made certain that she wouldn’t think much of herself. She took care of her daughters. She cleaned the house. She polished the silver. She ironed sheets, babies’ socks, and underwear. She landscaped the yard, mowed the grass, watered the gardens, fed the horses, pulled the weeds, canned fruits and vegetables, saved seeds, and most importantly, she cooked. If she could, and she found ways, she drank to numb herself. Just a little, just enough to quiet things down.

She says all she wanted was a thank-you, someone to acknowledge how hard she worked—whether it was her husband, who didn’t, or her own mother, which was never going to happen.

She still can’t really explain why she did so much because her own mother had never taught her how. She says all she wanted was a thank-you, someone to acknowledge how hard she worked—whether it was her husband, who didn’t, or her own mother, which was never going to happen. At the very least, her mother-in-law could have thanked her for tending to her son’s whims, being the head chef at Jenny’s, and caring for her grandchildren. But nope.

There she was, apron tied around her waist, making pierogi, kielbasa, roast beef, fried chicken, hand-cut French fries, borscht, and deviled eggs. Her husband, vacant at best, was either in the mills or in his garden. And her mother-in-law was over her shoulder, criticizing her every move, from child rearing to pierogi stuffing.

*

My mom is a great cook. She comes by it naturally, and she is obsessed with it. My mom will be the first to tell you she has an eating disorder—then she will say it’s just like how her daughter (me) is an alcoholic. So much for anonymity.

At a very young age, as she tells it, she found comfort in food. Food was love. Her mother was cold, her father was an alcoholic, and mostly she was left alone. Lots of parents tell stories about walking miles to school in the cold. In 1949, at five years old, in her dirty little dress with her messed-up hair, no shoes, and a tiny bag with a pencil and piece of paper, my mom was put on a bicycle. Her mother pointed and said, “The school is that way.” She’ll tell it that she never had a birthday party until she was old enough to give herself one.

It was her Uncle Frank’s fault. Occasionally, they would go to her grandfather’s house, where Frank still lived. Maybe he was babysitting, because she doesn’t remember her mother being around when it would happen, but Frank baked bread. He learned to bake in France and made big buttery loaves. He made firm, squat loaves full of seeds. Most importantly, he sweetened dough and fried it.

Frank cleaned my mom’s face and hands, put her in fresher clothes, and brought her into the kitchen. She sat at a curved bench before a window with the small kitchen table before her. Frank stood on the other side of the table, a pile of flour between them.

Her grandfather’s house was equipped with a potbelly stove that heated the room. Frank took a kettle of milk from the stovetop and motioned over it with his hand: “Not too much steam, you don’t want it too hot.” He spooned yeast into it and set it on the counter. My mother watched as it become foamy. He pulled a jar of flour and water from the top of the icebox.

This is what my mother recalls in her daydreams, sleep dreams, and whenever she still tells this story. This is where the emotional exchange happens.

“This is levain,” he explained. “We will make a poolish so this bread will rise.” The levain smelled like mushrooms, earth, yeast, and alcohol; it was interesting and sour.

She dipped her finger in and tasted it. “Mmm,” she exclaimed.

“That’s what gives bread the flavor you love so much,” he told her.

They spent the afternoons together mixing dough and getting the kitchen as hot as possible. My mother helped roll out the bread. She pinched it closed before placing it in the long loaf pan, which she had smeared with butter. After Frank put it on top of the stove, she didn’t move for two hours, until it was ready to bake. She read Archie cartoons and flipped through his cookbooks and recipe notes as she waited. Every couple of minutes, she looked up to see the level of the loaf because she knew that when it peeked from the top like a cloud, it was ready. Frank gave her mittens to wear while she put it in the oven. The hiss and crackle of the logs from inside the stove were the perfect accompaniment, especially when rain began to fall. When she got home that night, her mother would likely still be at work, and if or when she got home, she would still be cold and vacant. My mother would put herself to bed, lightly shivering until her body heat accumulated beneath the covers. She’d fall asleep dreaming about the day with Frank and the bread.

When he opened the oven, the champagne-like smell of yeast and caramelized butter permeated the room. So thick you could feel it on your skin. The sweet smell stuck in your hair for days.

“Can we cut it?” She asked this every time a loaf came out.

“No, we have to wait.”

When they finally cut into a loaf, Frank had a method.

This is what my mother recalls in her daydreams, sleep dreams, and whenever she still tells this story. This is where the emotional exchange happens. This is how food becomes your comfort, your companion, your best friend.

Frank sliced the bread one hour after he pulled it from the oven. There’d still be a little steam from its insides. I know he didn’t want to slice it yet, but he did it for me. He slathered it with the butter he’d made from churning the cream he bought from the farmers at the Fifth Avenue Sunday market. He’d leave that butter out for days. The fragrance became ripe, like a deeply marbled blue cheese. Then he coated all the butter with a thick layer of sugar. Then—the strangest part, that back then didn’t seem strange at all—he poured a small amount of boiling water over it. Just slow enough to melt the sugar and butter right into the bread.

Frank would sit down next to her and for the rest of the day, she was allowed to eat as many pieces as she wanted while they listened to the fire and the rain, if it was raining, and read the newspaper together.

_____________________________________________

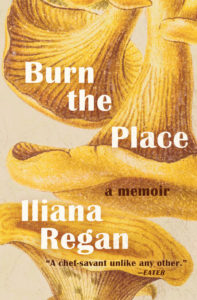

Reprinted with permission from Burn the Place by Iliana Regan, Agate Midway, July 2019.

Iliana Regan

Iliana Regan is a self-taught chef. She is the founder and owner of the Michelin-starred “new gatherer” restaurant Elizabeth and the Japanese-inspired pub Kitsune, both located in Chicago. Her cuisine highlights her midwestern roots and the pure flavor of the often foraged ingredients of her upbringing. A James Beard Award and Jean Banchet Award nominee, Regan was named one of Food & Wine’s Best New Chefs 2016.