Prison is boring. It’s noisy, and it’s bright. All around you, all the time, every day, there are people, unless you’re in solitary, which I might enjoy if I knew I could leave when I wanted, which you cannot. Moreover, you aren’t allowed pens or pencils or sometimes even books in solitary. I tolerate humanity’s crush in order to be allowed to write. I behave beautifully so that I have paper, pens, and occasional access to a computer. I suffer for my art.

In my nun’s narrow bed at night, I hear covers rustling. So much whispering, so much snoring, so many people breathing—I might as well be sleeping with all of them. These are not, almost to a one, people I want to spend time with, yet together we do time. Time binds us, time flattens us out, time makes us familiar. So much time, so many people. I’ve never liked people, and now I like them less. They’re nearly all women, too; I’ve so little to play with. There are male guards—the less said about them, the better. I see them, the guards, terrifying the vulnerable inmates. They’re bullies, these men living their fantasies of power, as if their squalid teenage dreams cracked open and spilled incarcerated candy at their feet.

Prison company is bad. Prison food is worse. Even when you game the system, the food is lamentable. My kingdom for a delicately roasted parsnip, a perfectly cooked rack of lamb, a slice of coppa di cinghiale, a glass of Montevertine Le Pergole Torte. I’d kill for some biodynamic Tuscan extra-virgin olive oil. This last is not an overstatement, nor is it a threat—not yet, anyway. It’s also the only item on that list that I have any chance of getting here in the pen.

For the first time in more than a decade, I have a job—you can’t freelance in prison. I work in the library. I am not yet allowed to help people find books. I’m not yet allowed to check books out or check them back in—these jobs come with nearly unfettered access to a computer, and they’re positions of much envy. I stack books on a cart, I push the cart to the stacks, I find the books’ rows, and I return them to their predetermined locations. It’s dull work, humiliating and borderline pointless, but at least it’s not physical. At the end of my working day, I’ve got energy to write. Rolling my cart under the numerical guidance of the Library of Congress, I mark my days by remembering meals, and they’re not the meals you’d imagine. It’s not a parade of gourmet dishes, baroque as popes and twice as rich. No fantasy ortolan, delicate songbird bones crunching as fat runs down my veiled chin. No Thomas Keller–orchestrated dinners, each plate a bar played in a grand, pure symphony that edges on Wagnerian excess. No savory, silky feast of the seven fishes; no effusive, bubbly banquet of El Bulli foams, extractions, and mousses.

No, the dishes my memory presents me with are stark as a wimple. A simple plate of cut tomatoes oozing their sun-warmed guts, drizzled with oil, and sprinkled with flaky diamond-white salt. A fat slice of fresh, hot bread spread with daisy-yellow butter. The crackling skin of a roast chicken spitting hot fat into my mouth. A bowl of berries daubed with obscenely thick cream. They’re the foods, God help me, my mother would have served.

*

People tend to think that the most natural stories begin at their beginning and unwind through their middle to their completion, and sometimes they do. But that narrative structure is only as true as time, which is to say it’s as much a construct as a house or a dress or a turducken. Stories are, like justice or a skyscraper, things that humans fabricate. I started this story, for example, somewhere near the end, but that doesn’t make it any less true. It makes it artful, but not false. Let me pause to tell a story from when I was a little girl. It’s also true. Everything here is true because, really, why would I lie.

When I was very young—long before I ever lost my virginity or even kissed a boy, around twelve, I think—I had a vision. I imagined throwing a lavish affair, a sort of punctuation mark on my adult life. I saw myself inviting all my lovers, present and past, to a dinner party. I knew even as puberty was dawning, fluffy and pointed as a kitten, that my life would be rich with men. These men, I imagined, would be plentiful, interesting, attractive, and, above all, devout.

For the first time in more than a decade, I have a job—you can’t freelance in prison.In my imagination, I’d send each of them an invitation. Something etched in black spiky ink on heavy stationery—weighty as Schlag, textured as flan, colored the delicate white of the fat marbling a prime cut of steak. Each man would RSVP yes, delightedly, each unknowing that the invitation was not for him alone, and each thrilled to his core to see me. I could not then imagine I’d ever have a lover who would not want to see me again. I still can’t.

I envisioned a long dinner table, so much longer than it was wide, shiny and black as a beetle’s carapace, lined with tall straight-backed chairs that were topped with long, spired skewers, like the spikes in an iron maiden. In my imagination, these men I loved would sit together, ranged along the two sides of the table, joined by their adoration for me, and united in their befuddlement. They wouldn’t know one another. They wouldn’t know why they were there, and I would sit at the head of the table, smiling.

In my jejune imagination, my dream lovers were uniform, each as beautiful, masculine, and replaceable as an Arrow shirt model. Really, what does a twelve-year-old know about men. To a girl, a man of thirty is impossibly old, if inconceivably desirable and infinitely replaceable. At twelve, my lust was little more than a vague mauve ache nestled in my cotton panties. I knew that lust was a dangerous thing, but I wanted these men to lust for me because, even though I didn’t know the precise shape and weight of lust, I knew that lust was power—and I wanted power even then.

Thus my painfully specific imagined feast, the formal invitations, the long and slick black table, the two martial lines of men, the spiky dining chairs, the shiny cutlery, the glinting of glasses, the smell of roast meat, the quiet sound of polite if menacing conversation, the palpable bewilderment, and my sitting poised and plumped as a Persian cat at the table’s head. Thus my fantasy of power. This from the fecund imagination of a twelve-year-old girl.

It’s amazing I didn’t turn out worse than I did.

*

It’s not as dangerous as I thought it would be, prison. A couple of women have tested me, but being a tall, known murderess tends to keep potential harm at bay. Just after I first arrived, two women—what do they say?—got all up in my face. It was kind of adorable, really, their desperate grab for dominance. They cornered me as I was exiting the shower; I looked down at them, their faces hot with inarticulate want, and told them that I’d killed a man with a piece of fruit. I let that assertion sit, and I saw their limited wonder about their own personal and painful Achilles’ heels. Then I swept out of the shower area, stunned silence in my wake. These women were merely petty felons clad in stolen dominance, you see, while I was a naked, dripping murderer. There’s a lot to be said for intimidating intelligence and a dearth of conscience, and I possess both.

It didn’t take long for the forensic psychology and criminal justice students to start fluttering to me, like common gray moths to a bonfire. Two weeks after I’d landed at Bedford Hills Correctional Facility, and I’d received my first interview request from a Ph.D. candidate. One request became two, then three, then more. Like hail dropping from the sky, eager students fell before me, jostling each other for my attention. It was delightful to be so avidly courted by so many keenly interested young things. I felt like the belle of the carceral ball.

In my jejune imagination, my dream lovers were uniform, each as beautiful, masculine, and replaceable as an Arrow shirt model.I was given batteries of standardized tests. I acquiesced to MRIs and genetic testing. I was asked repeatedly about my childhood. I was plied with cans of mineral water and the finest snacks the vending machines could provide, and I gave my permission to have my psyche plumbed and prodded, plumped and pushed. The students were mostly thirty-year-olds, who, irrespective of gender, wore studious glasses and the kind of asexual, atonal clothing that functions like mental saltpeter. But I’ve always found that being the center of attention is an implicitly erotic state, and I spread my exotic wings under the students’ bland collective gaze. The Hawthorne effect is real—as I was observed, my behavior changed, not always innocently.

For one thing, I knew that the students’ interest in me was in direct proportion to how well I conformed to their prepackaged expectations, and I knew that the more I teased the edges of their working diagnoses, the longer I could keep them hanging on. I enjoyed my place in the limited limelight. I wasn’t going to let my audience down, so I bubbled in the responses that would make me spicy in these students’ eyes. And above all, I knew what these darkly optimistic students were hoping to find.

It wasn’t hard. I do have a long, florid history of using aliases. I do have a delicious record of nonconformity. I was convicted of violent crimes predicated upon a piquant mélange of impulsivity and preparedness. I genuinely lack remorse. And one of the reference books in the Bedford Hills library stacks happens to be the DSM-IV, out-of-date but extremely useful. Knowing what I knew, it was easy to lay the derangement on thick when I wanted and to drizzle it with delicacy when I determined that was the right approach. I can’t, of course, tamper with the MRIs, but even neurologists admit that when it comes to mapping the human brain, we are Christopher Columbus: motivated by dubious ethics to search for a route to Asia and “discovering” these America-shaped continents by mistake. Brains are an imprecise science, in short. Easy to fake and even easier to deceive.

I am special, the students intimate. I am valuable, their breathlessness suggests. I am, as one excited student exclaimed, “A perfect specimen of a female Anti-Social Personality Disorder!”

To this, I laughed. I know what I am. It may not appear in the DSM-5, but just because you can’t prescribe a pill for us doesn’t mean we don’t exist.

Indeed, I am the Bronze Copper of psychopaths, a big, beautiful auburn butterfly that flaps her darkling wings as she eats. I am rare, and sequestered in this endlessly gray penal institution, I am endangered. I first suspected I was a psychopath years ago with an armchair test of twenty-six questions, but even before I sat down with my computer and ticked “agree” for “I tell other people what they want to hear so that they will do what I want them to do” and “Love is overrated,” I knew that I was different. I merely lacked a name for how.

One mark of psychopaths, or so I’ve learned, is that we calculate an action’s personal benefits before we take it, and it benefits me to proclaim my psychopathy, both in prison and out of it. Here at Bedford Hills, my psychopathy earns me a wide berth. There in the world, my psychopathy sells better than sex—and sex plus psychopathy, well, that’s a heady delight.

As a woman psychopath, the white tiger of human psychological deviance, I am a wonder, and I relish your awe.

You who call women the fairer sex, you may repress and deny all you want, but some of us were born with a howling void where our souls should sway.For a long time, the scientists who study such things were reluctant to admit the existence of women psychopaths. Even with all the cliché evidence—the bad mothers who leave their children to cry in wet beds, the nurses who “help” their unwitting patients to die, the black widows with a wealth of dead husbands—people did not want to believe. Female psychopaths, researchers eventually realized, don’t present like the males. To which I respond: No shit. We women have an emotional wiliness that shellacs us in a glossy patina of caring. We have been raised to take interest in promoting the healthy interior lives of other humans; preparation, I suppose, for taking on the emotional labor of motherhood—or marriage; either way, really. Few women come into maturity unscathed by the suffocating pink press of girlhood, and even psychopaths are touched by the long, frilly arm of feminine expectations. It’s not that women psychopaths don’t exist; it’s that we fake it better than men.

Take a quick trip through history, and you see no shortage of flashy female psychopaths. Elizabeth Báthory, who killed between eighty and a few hundred people, mostly women, in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, before being walled inside a castle tower. Chile’s La Quintrala, colonialism’s poster girl, who slaughtered about forty indigenous people. Darya Saltykova, Muscovite, who dispatched a hundred or so serfs, mostly girls, in the eighteenth century. Delphine LaLaurie, who tortured and killed numerous slaves in her nineteenth-century New Orleans home. Women like these punctuate time with their bloody body count, yet people are still disinclined to believe. Even as Victorian women slayed whole families with heaping helpings of arsenic to reap health insurance monies; even as Aileen Wuornos shot her seven johns; and even as Stacey Castor’s matricide got her fifteen minutes of fame on 20/20, people didn’t want to believe. Feminism comes to all things, it seems, but it comes to recognizing homicidal rage the slowest.

You who call women the fairer sex, you may repress and deny all you want, but some of us were born with a howling void where our souls should sway. I am a psychopath—and whatever their reasoning and whatever their diagnoses, the eager psychology and criminal justice students are right to study me. And if they’re wrong, I still enjoy their attention, and I’ll do what I must to encourage it.

Aside from the eager Ph.D. students—so well groomed and so poorly dressed, especially the men—I receive few visitors here in prison. My father comes; my sister has visited twice; my brother has sent his regards. Emma has applied to visit, but I won’t allow it, for obvious reasons. I am impressed that she would consider leaving her apartment for the long, intricate trek to Bedford Hills.

(Though perhaps she knows I’d never approve the visit and she’s merely applying to toy with me. That’s not a possibility I’m willing to indulge, on the off chance that she appears some Sunday afternoon, dripping Vivienne Westwood and Guerlain Nahema. I don’t even open Emma’s letters.)

It’s one small mercy that here in prison we don’t have to see anyone we don’t choose to see. In this way, prison is beautifully unlike real life. In real life, people from your past litter your life like cockroaches, popping out of crevices and scuttling across the dark. In the outside world, you can’t escape fate’s cruel crossing. You turn a corner, and there buying a hot dog is the editor of your college paper; you engage in conversation; you go out for lunch, and then to dinner, and then into bed, and then you love. Love is the languid sigh of death, and no one will ever convince me otherwise.

Prison may be the hell of other people, but at least it’s not a hell of people you love.

__________________________________

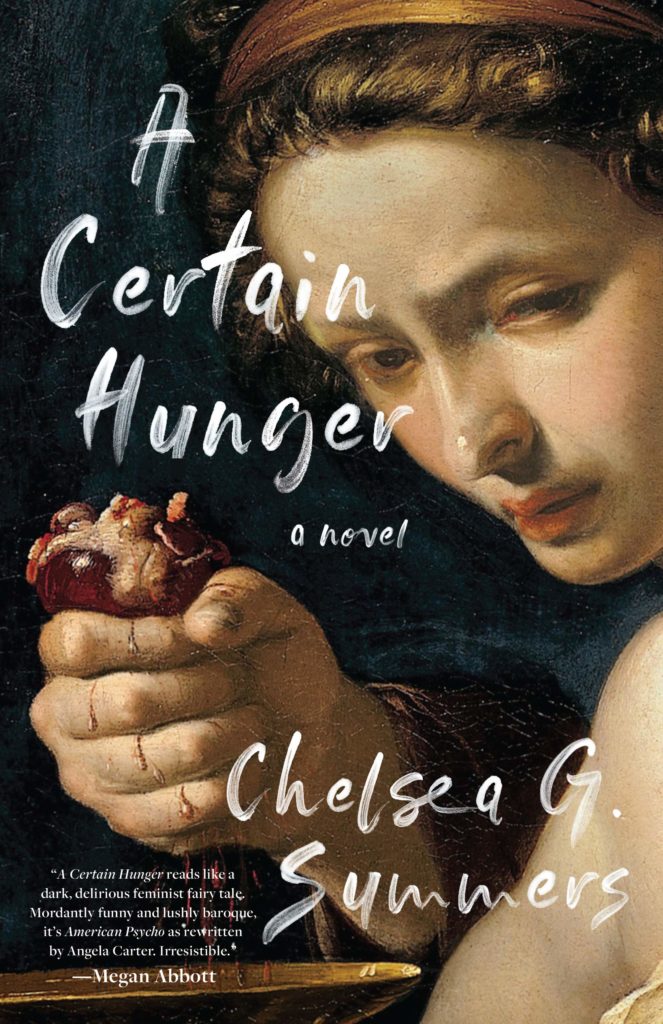

Excerpted from A Certain Hunger by Chelsea G. Summers. Excerpted with the permission of Unnamed Press. Copyright © 2020 by Chelsea G. Summers.