A Brief Literary History of Gay and Lesbian Bars

Jeremy Atherton Lin on Finding Sites of Literary Sociability

At a certain kind of joint, slumming it may be a sip away from hobnobbing with literati. As ever, it helps if you’re cute. In the late 1940s, the directionless blond undergrad Joe LeSueur ventured into Maxwell’s in downtown Los Angeles, a rough saloon populated by hustlers, drifters and the gender nonconforming. Le Sueur’s fascination with the scene was at once othering and hankering: “‘It’s so sordid,’ I remember purring in appreciation the first time I entered the place with two other thrill-seekers from USC, ‘sordid’ being a key word in our lexicon, the standard to which we held our libidinous experiences.”

The twink drew the attention of Christopher Isherwood, though they swiftly abandoned attempts at conversing amid the din. Another night, Paul Goodman, a shabbily dressed, unprepossessing author from New York, persisted. LeSueur was brought into his coterie, where the chatter was “like nothing I’d ever heard—knotty, incisive, often with a psychoanalytic thrust.” The talk was of poetry and The Partisan Review, Genet and Wittgenstein. A band of gay bohemians, LeSueur noted, more bohemian than gay—“they weren’t run-of-the-mill queers defined by their sexual orientation but fiercely independent intellectuals who happened to be homosexual; and to me, they constituted a new breed, an elite brotherhood whose ranks I instantly wanted to be a part of.”

Transplanting to New York, LeSueur was taken by Goodman to “the crypto-queer Sam Remo, the macho Cedar Street Tavern, and the blustering White Horse Tavern.” Through Goodman, he came to know Frank O’Hara, that centripetal force (“center of all beauty!”). By 1957, when O’Hara wrote the untitled poem that opens “I live above a dyke bar and I’m happy,” he and LeSueur were sharing a third-floor apartment, actually two doors down from The Round-Up. (Or was that Stirrup, or Silver Spur? LeSueur later flippantly misremembered.) According to the date and location, I’d suggest it was the Bagatelle—“the Bag”—a Mafia-owned venue at 86 University Place that counted writers Ann Bannon and Audre Lorde among its regulars. LeSueur would peer out his window, attempting to discern the psychosexual dynamics playing out on the street. He surmised the men who dropped in to pick up lesbians must be the hetero version of trade queens, those gay men with a preference for straight guys who lend their bodies disinterestedly.

A photo from August 1955 of patrons inside the Green Door, a lesbian bar in North Hollywood. Photo via the Mazer Lesbian Archives.

A photo from August 1955 of patrons inside the Green Door, a lesbian bar in North Hollywood. Photo via the Mazer Lesbian Archives.

Lorde has disclosed a different dynamic inside—the coded lesbian roles of mommies and daddies. There were violent consequences for not getting the garb right, for failing to read the room: “If you asked the wrong woman to dance, you could get your nose broken in the alley down the street by her butch, who had followed you out of the Bag for exactly that purpose.” The implications ran deep for Black lesbians like Lorde, who wrote:

For some of us, however, role-playing reflected all the depreciating attitudes toward women which we loathed in straight society. It was the rejection of these roles that had drawn us to ‘the life’ in the first place. Instinctively, without particular theory or political position or dialectic, we recognized oppression as oppression, no matter where it came from. But those lesbians who had carved some niche in the pretend world of dominance/subordination rejected what they called our ‘confused’ lifestyle, and they were in the majority.

In San Francisco in the early aughts, I lived directly above a dyke bar. Of sorts: El Rio was a chummy neighborhood dive run by lesbian academics, queers of color and FTM hipsters. It had opened as a Brazilian leather bar in 1978. By my time there, it hosted post-punk gigs and poetry readings. On Sundays, the back patio filled with salsa dancing, which I watched from the fire escape. I co-hosted monthly film screenings in a sideroom, the most popular being Wild Style, the graffiti documentary. The manager suggested we provide markers to encourage the crowd to tag the bathroom walls. For my contribution, I block-lettered some favorite lines from Lynda Barry’s novel Cruddy. Within weeks, someone had written PRETENTIOUS with an arrow pointing to my citation.

Gay bars made their own lexical dent by way of furtive codes, ribald commentary and camp parlance.

Over at the toilets in The Lexington—a proper dyke bar, humid and rollicking—someone scrawled “Michelle Tea does not speak for me.” Michelle was a pal and neighbor, and one of the few writers in town whose work circulated beyond the local photocopy-and-coffeehouse scene. Michelle’s novel Valencia, first published in 2000, begins: “I sloshed away from the bar with my drink, sending little tsunamis of beer onto my hands.” In the pages that follow, the narrator survives on booze and bagels, tries out various forms of freelance sex work, brings down a bathroom sink when she sits on it to urinate. Her singular voice hardly seemed an attempt at articulating the concerns of an identity group. I put the detractor’s barb down to sour grapes.

In the days before Twitter, aspersions cast on a bathroom wall seemed far-reaching. Michelle shrugged it off. She hadn’t made claims to speak for anybody. Years later, when I brought up the incident, Michelle was sagacious. To be spoken for may be something to urgently seek out—or resist. Moreover, Michelle pointed out, the platforms remain too limited for a range of people to speak for themselves. There will always be someone else waiting, while their frustration justifiably builds. To speak for (or as) is, of course, a contested stance. Dilemmas of positionality may never be solved over a drink (or a brawl) in a bar; it just happens I first encountered the issue through that bathroom wall plaint.

Outside San Francisco’s Lexington Club, a legendary lesbian bar that closed in 2015. Photo by Kathy Drasky/Flickr.

Outside San Francisco’s Lexington Club, a legendary lesbian bar that closed in 2015. Photo by Kathy Drasky/Flickr.

The irony was, Michelle was constantly passing the mic. She took the Sister Spit spoken word collective across the country, introducing a younger generation to Eileen Myles on the 1997 tour. Radar, her series at the then-new San Francisco Public Library, allowed voices (including mine) that otherwise skidded across barroom floors to echo through a marble hall. San Francisco at the turn-of-the-century was scuzzy but not slacker. Queer readings were held at the womyn-led Bearded Lady café and the men’s sauna Eros (in the lobby so that lesbian and trans writers could participate). Such events inherited a legacy from the North Beach scene of decades past. Peggy Tolk-Watkins, a poet from Black Mountain College known as “queen of the dykes” established the Tin Angel in 1953. Miss Smith’s Tea Room followed, a lesbian pickup spot with a sawdust floor and readings on Wednesdays.

Two other Black Mountain alumni set up The Place, where gay poet Jack Spicer hosted Blabbermouth, a weekly open mic. Other gay bars made their own lexical dent by way of furtive codes, ribald commentary and camp parlance. The poet Aaron Shurin has described the men at his first gay bar, the Rendezvous in San Francisco’s Tenderloin in the early 1960s, as “made of silly gestures and dramatic arches and too-muchness and high language, of alliteration and sibilance and “sensibility.” Gay identity may be a kind of speech act—and a gay bar not just saloon, but salon.

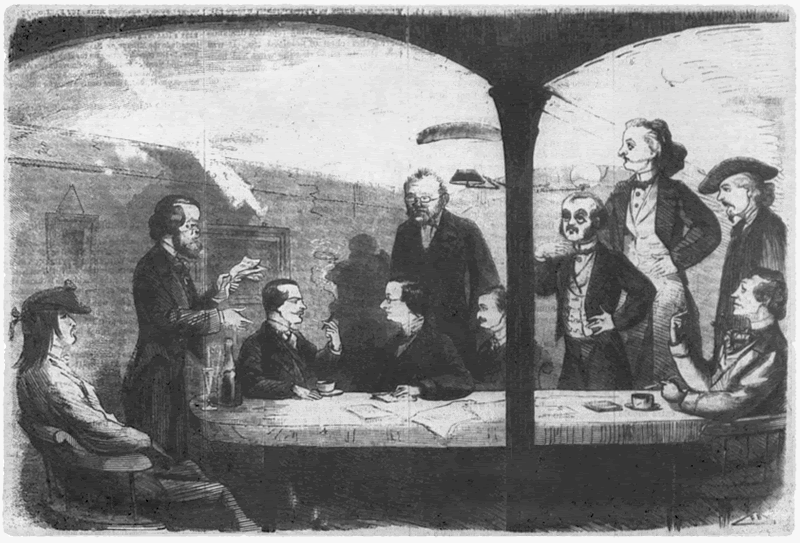

An image by Frank Bellew from the February 6, 1864 issue of Demorest’s New York Illustrated News, depicting Pfaff’s.

An image by Frank Bellew from the February 6, 1864 issue of Demorest’s New York Illustrated News, depicting Pfaff’s.

A century earlier, Walt Whitman frequented Pfaff’s Beer Cellar on Broadway near Bleecker in what was then considered central Manhattan. Pfaff’s operated there for a short time from 1859, below and discrete from the Coleman Hotel. Guests entered through a sidewalk hatchway. There, the poet sat with his young lover and other laboring men. The bohemian element comprised not so much a literary elite as penny press journos and feuilletonists, acerbic and unknown. Also in the mix were Irish and German immigrants, some women (still a rarity in the city’s taverns) and men for whom the bonhomie allowed for expressions of homo-affection (“my darlings and gossips,” Whitman called them). By the early 1970s, the DJ David Mancuso hosted The Loft parties in a room upstairs, an intimate space that helped inspire Dancer from the Dance, Andrew Holleran’s beloved 1978 novel about the era’s feverish clone enclaves. I find myself unsurprised by the coincidence: While writing my book Gay Bar, a little dig on a given site frequently revealed decades, even centuries, of queer eventfulness.

To Whitman, the hubbub of a barroom is peeped through a lacuna in the door frame, and the charge of the night remembered for the gaps in conversation.

Such histories may have been authored through confabulation and myth. Whitman, for instance, portrays himself in a bar as the silent type, surely aware of this allure to both a searching reader and someone cruising for sex. At Pffaf’s back in the early 1860s, according to the historian Christine Stansell, Whitman would have witnessed “rhetorical jousts of insult and badinage” in “a sharp-edged repartee altogether opposed to the polite puffery of genteel literary circles.” The place provided Whitman a new sense of his place as a writer: Having long considered himself outside the publishing establishment, at Pffaf’s he was adjacent to jobbing wits—wordsmiths in the manner of copper- or locksmiths. He could participate in the conversations but, in retrospect anyway, fancied himself at a remove, as in his Calamus poem ‘A GLIMPSE.’ It begins:

A GLIMPSE through an interstice caught,

Of a crowd of workmen and drivers in a bar-room around the

stove late of a winter night, and I unremark’d seated in a

corner,

Of a youth who loves me and whom I love, silently approaching

and seating himself near, that he may hold me by the hand,

Whitman insisted that, while delighting in the young men around him raising a glass and their voices, his own pleasure “was to look on—to see, talk little, absorb.” Hence the laconic slouch romanticized in the poem, which continues:

A long while amid the noises of coming and going, of drinking

and oath and smutty jest,

There we two, content, happy in being together, speaking little,

perhaps not a word.

I chose those final lines as the epigraph to my book, unable to resist the poet’s self-characterization as companionable wallflower. To Whitman, the hubbub of a barroom is peeped through a lacuna in the door frame, and the charge of the night remembered for the gaps in conversation.

__________________________________

Gay Bar: Why We Went Out by Jeremy Atherton Lin is available via Little, Brown and Company.

Jeremy Atherton Lin

Jeremy Atherton Lin is the author of Gay Bar, a New York Times Top Book of 2021 and recipient of the National Book Critics Circle Award. His essays appear in numerous places including the Paris Review, the Times Literary Supplement and the Yale Review.