On November 7, 1800, a decree was issued in Paris requiring women to obtain a permit in order to wear pants in public. The French writer George Sand (the penname of Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin) defied the order by donning men’s attire and freely roaming the streets, sans permit. Once outfitted in her grey wool garb and boots, Sand felt “secure on the sidewalks,” she wrote in her autobiography. “I flew from one end of Paris to the other. It seemed to me that I could have made a trip around the world… No one knew me, no one looked at me, no one found fault with me; I was an atom lost in that immense crowd.”

At a time when “proper” women would have risked disgrace by being out alone—their place was in the home, after all—Sand was reveling unescorted in the streets. She was a secret female counterpart to the male flâneur, the man of leisure who strolled the boulevards to cultivate what Honoré de Balzac called “the gastronomy of the eye.” Although Sand’s medium was the pen, her peripatetic explorations of 1830s Paris helped pave the way for those who would eventually take their cameras and roam the streets to capture the goings-on of public life: women street photographers.

*

Not long before Sand was flying around Paris, a French inventor by the name of Nicéphore Niépce was looking for a way to make images without having to draw them. In 1826, he had the idea to use a device popular in the Renaissance, the camera obscura, to create a projection upon a treated pewter plate. Left alone for eight hours, the sun etched the view onto the surface, resulting in the world’s first photograph. The image reveals a tangle of rooftops and buildings. It is a rustic thing, all texture and shapes, with few details—yet it is hard to overstate its importance.

Defining “street photography” is not for the faint of heart and has given rise to much debate.With photography still in its nascent stage, Sarah Anne Bright and Constance Fox Talbot were experimenting with the medium in Britain. They both made photographs in 1839—and each has alternately been credited with having been the first woman to do so. In 1843, amateur botanist Anna Atkins created a book entitled Photographs of British Algae, composed entirely of cyanotype impressions. It was the first book ever to be photographically printed and illustrated.

Photography’s early years were filled with tinkering and rife with images of nature and simple scenes. It was not until the French artist and chemist Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre came up with his namesake daguerreotype in 1839 that the world had its first commercially successful photographic process.

At this point innovations in photography were most notably taking place in the West—our focus here, given street photography’s strong Western roots—but that is not to say that photography was not happening elsewhere. Europeans brought daguerreotype cameras to China as early as the 1840s, for instance, and soon thereafter Chinese photo studios were developing their own style of photographic representation. In India, daguerreotype cameras were available in Calcutta a year after their invention and by the 1870s, Indian photographers were opening commercial studios.

Daguerre had used his new process to create the first known photograph of a human in the late 1830s. The image, captured on a silvered copper plate, reveals a scene of Boulevard du Temple in Paris. Strolling figures passed by too fleetingly to be registered by the plate’s long exposure, but a man getting his boots shined remained still for long enough to be immortalized forever in the historic image. Would it be a stretch to call this the first street photo?

Defining “street photography” is not for the faint of heart and has given rise to much debate. It was neither codified in a manifesto nor formally clarified early on. As described by the Encyclopaedia Britannica, street photography is “a genre of photography that records everyday life in a public place… Street photographers do not necessarily have a social purpose in mind, but they prefer to isolate and capture moments which might otherwise go unnoticed.”

Laura Reid, “Sun Worship,” 2017 © Laura Reid

Laura Reid, “Sun Worship,” 2017 © Laura Reid

While the discourse over what comprises street photography may endure into eternity, the body of work by Staten Island resident Alice Austen could serve as a model for the genre itself. She was ten years old in 1876 when her uncle gave her a camera and she spent the next 50 years making more than 7,000 photographs, processing them herself in a second-floor closet turned into a darkroom.

A bicycle enthusiast, she cruised the streets with 50 pounds of gear in tow, seeking subjects to photograph. She took photos of anything and everyone who interested her, from the high life of Staten Island, to the street sweepers, suspenders sellers, postmen, policemen, fishmongers, organ-grinders, shoeshine boys, and newsgirls of lower Manhattan. What she was doing all the way back then is not very different from what street photographers are doing today.

*

Photography took a leap forward when George Eastman introduced the Original Kodak camera in 1888. Small enough to hold in the hands, the fixed-focus camera came loaded with a 100-exposure roll of film. Now, rather than having to struggle with cameras that used a glass-plate negative for each exposure, photographers could shoot with a simple and portable machine. Eastman Kodak’s introduction of the Brownie in 1900 made photography yet more accessible and affordable.

The 1920s and 30s gave rise to a number of historic women photographers whose work informed what we now call street photography.However, the new cameras didn’t have the quality required by professional photographers, which is why Jessie Tarbox Beals, dressed in the typical street-skimming dresses and large hats of the day, lugged around her cumbersome large-format camera, along with a tripod and the requisite gear. Beals was hired by the Buffalo Inquirer as a staff photographer in 1902, making her America’s first female news photographer.

While most women photographers at the time were photographing friends at home or making portraits in the studio, Beals was out in the world taking photos of real life, and with moxie. She even taught herself to use flash powder, making her the first female night photographer. And her influence was not lost on the world. As the Library of Congress notes, “Her courageous example encouraged other women to pursue photography.”

Although the technological advances in photography were becoming more available globally, gender roles in some parts of the world meant that many women were far from being able to buy a camera and freely roam the streets (as is still the case today). But in the United States, the 1920s and 30s gave rise to a number of historic women photographers whose work informed what we now call street photography.

Dimpy Bhalotia, “Shoulder Birds,” 2018 © Dimpy Bhalotia

Dimpy Bhalotia, “Shoulder Birds,” 2018 © Dimpy Bhalotia

There was Berenice Abbott, who strove to document a changing New York City; photojournalist Margaret Bourke-White, who in 1930 became the first Western professional photographer allowed into the Soviet Union; and of course Dorothea Lange, who left her San Francisco portrait studio to join the government’s Resettlement Administration. Her work included some of the most enduring photographs we have today, including her “Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California” of 1936, which has become one of the most famous photographs in history.

During this period a group of early women pioneers of street photography emerged, coaxed forward by another advance in technology. In 1925, Leica launched the company’s first commercially available 35mm camera. It was small and equipped with fast shutter speeds and well-crafted lenses, affording those making candid photographs in public a discreet way to do so with high-quality results.

Elena Alexandra, “Sleeping Beauty,” 2019 © Elena Alexandra

Elena Alexandra, “Sleeping Beauty,” 2019 © Elena Alexandra

In Paris, photographer Ilse Bing bought the new camera in 1929, her subsequent work earning her the moniker “Queen of the Leica.” And it was a Leica that Helen Levitt purchased in 1935 after being inspired by the work of street photography pioneer Henri Cartier-Bresson. Levitt’s images of New York City’s children and life in the poorer neighborhoods started appearing in magazines by 1939, and by 1943 she had a solo exhibition at MoMA. She would spend the next 40 years walking the streets to catch, as the New York Times described, “fleeting moments of surpassing lyricism, mystery and quiet drama.” Echoes of Levitt’s influential work can still be felt in photographs being made today.

Danielle L. Goldstein, “Alone,” 2019 © Danielle L. Goldstein

Danielle L. Goldstein, “Alone,” 2019 © Danielle L. Goldstein

Meanwhile, in Paris, German-born Marianne Breslauer spent the late 1920s and 30s focusing her lens on street scenes ranging from the homeless along the river Seine to the horseraces at Longchamp. Breslauer spent her time walking through the streets, finding poetry in the mundane: one of the hallmarks of modern street photography. In a photo from 1937 she presents a sliver of a moment that would otherwise have gone unseen. In the image, an elegant figure in a hat lights a cigarette, with her glove and a matchbox in her hand. The wall before which she stands is a chaos of text and texture, and acts as a screen for the shadow of a lamppost that takes on the look of cartoon-character companion. It was an unremarkable split second, made remarkable for having been frozen by Breslauer’s camera.

In India, Homai Vyarawalla, known by her pseudonym Dalda 13, was recognized as the country’s first woman photojournalist. Working from the 1930s onward, she was often seen riding her bicycle on the streets of New Delhi with a camera bag slung over her shoulder. A few years later, another Indian photographer, Li Gotami Govinda, would go on assignment in western Tibet to create one of the last records of life and culture there before the Chinese occupation.

“Everyday life and where it was happening was what interested me.”It was also in the 1930s that Lola Alvarez Bravo began venturing out from her studio in Mexico City to start photographing what she called “the life I found before me.” Considered the first professional woman photographer in Mexico, Alvarez Bravo wore many hats in terms of her photography, but it was her personal work that pushed the boundaries for the time and place. The Center for Creative Photography, which owns her archives, describes how she moved “amongst the people along cluttered streets, observing them at work, in the marketplace, and at leisure, waiting for opportunities to capture informal moments in carefully composed scenes.”

And there was Vienna-born Lisette Model, who moved to New York City in 1938; just two years later, her work would be included in the inaugural exhibition of MoMA’s Department of Photography. There is a certain energy in Model’s candid photos—and with her proclivity for capturing the city’s quirkier characters, the result is a unique dynamic that still feels relevant.

*

Western women in the 1930s had come a long way relative to the Victorian social constraints of their predecessors, and the Second World War would do much to nudge gender roles further forward. Women photographers were allowed entry into jobs formerly reserved for men. In New York, Ida Wyman, already interested in photography, got a job at Acme News Pictures at the age of 16. Here, she explains, “in an all-male environment, I became both their first mailroom ‘girl’ and their first ‘girl’ printer.” During her lunch breaks she would shoot her “picture stories” on the street, which she started showing to editors who were receptive to her work. She would go on to have a long career, noting, “Everyday life and where it was happening was what interested me.”

Sandrine Duval, ‘In the Mood’, 2018 © Sandrine Duval

Sandrine Duval, ‘In the Mood’, 2018 © Sandrine Duval

Similarly, when a knee injury forced Vivian Cherry out of work as a dancer in 1945, she took a job at a photo lab that was short on male staff. Working with prints sparked an interest in photography and she spent the rest of her long life taking an abundance of remarkable street photos. Cherry’s admiration for Helen Levitt can be seen in her images of the city’s children, but those are just a fraction of her body of street work, which offers iconic glimpses of New York City, from the Lower East Side to Harlem.

Millions of women joined the workforce during the war, and things would never quite be the same afterwards. In the United States, Rosie the Riveter offered a new vision of female strength and determination, and attitudes about “a woman’s place”—the home—began to shift. When the war was over, most women were sent back to their abodes to resume domestic duties, but a new independence had taken hold. The genie was out of the bottle.

__________________________________

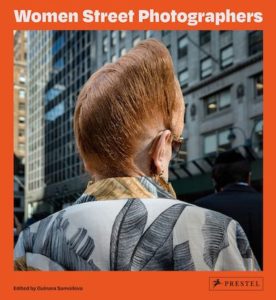

Excerpted from Women Street Photographers edited by Gulnara Samoilova © Prestel Verlag, Munich · London · New York, 2020. Text copyright © 2021 by Melissa Breyer. Lead photo credit: B Jane Levine, ‘Red Upsweep’, 2019 © B Jane Levine.