A Brief History of the Death Penalty in America

Maurice Chammah on the Country's Ambivalence Toward Democratized Killing

In every death penalty case, before Charlie Brooks and since, you will find the family members, the lawyers, the journalists, the prison workers—each of them touched, in ways large and small, observable and invisible, by the moment a person takes a life, the moment the state takes a life, and the many moments in between.

To everyone else, the death penalty can feel like an abstraction, a source of dinner table quarrels that reemerge when a major case hits the news and we marshal the arguments we’ve heard before, citing the Bible or statistics or anecdote to make our case for or against. Capital punishment is a long-standing tradition, close to a cultural universal over the long span of the human experience, but Americans have always viewed it with some ambivalence, and our history is accordingly erratic. Before the Civil War, the French writer Alexis de Tocqueville marveled at the “mildness” of American punishment (for those who weren’t enslaved, that is), and Michigan, Maine, and Wisconsin abolished the death penalty for good. Nebraska, meanwhile, kept carrying out executions until 1959, then stopped, then carried out three in the mid-1990s, then stopped again, then formally abolished the punishment in 2015, then voted to bring it back, and finally resumed executions in 2018.

There was no clearer policy expression of the idea that some people were irredeemable.

Even amid this turmoil, there was a moment, roughly half a century ago, when it seemed the death penalty would disappear from American society forever. Executions had fallen out of fashion by 1972, when the U.S. Supreme Court decided that the American system of capital punishment as a whole violated the Constitution. Instead of marking the death penalty’s end, however, this decision spurred its resurgence. States crafted a new system, and executions resumed and trended upward and the country reached a peak—nearly a hundred executions—in 1999.

This embrace of capital punishment coincided with a historic rise in violent crime that began in the 1960s and trailed off in the 1990s. Seeking to explain this trend, scholars have looked in many directions. Crime is often the product of impulsive decision-making, and young adults with less-developed brains are more likely to act impulsively; as the baby boomer generation came of age, the population of young adults ballooned. The closing of asylums and failure to improve public mental health systems meant that jails often took on the care of those suffering from mental illness. In the 1960s, American society also experienced sweeping transformations in its cultural and sexual mores, which produced new conditions—more unmarried young men, more children without parental stability, more cultural celebrations of violence—that help explain, if only partially, the rise in crime.

There was a moment, roughly half a century ago, when it seemed the death penalty would disappear from American society forever.

But cause and effect, action and reaction, also began to blur in myriad ways. An epidemic of crack cocaine use swept Black communities, but political choices criminalized the sale and use of the drug and turned prisons into places where those convicted of nonviolent crimes were acclimated by trauma to violence. The American creed of personal reinvention, which at times had inspired prison officials to focus on rehabilitation and redemption, was shelved as a naive indulgence. (The word “corrections” lingered in the names of state prison agencies, an aspiration for the future or a phantom limb from the past.) As lawmakers made it easier to get sent to prison and harder to get out, the number of incarcerated Americans ballooned from half a million to more than two million. Even at the death penalty’s height, it played a role in only a tiny fraction of murder cases, but executions were the ultimate symbol of a national culture that favored retribution, and they rendered sentences of twenty, forty, or sixty years in prison less extreme by comparison. There was no clearer policy expression of the idea that some people were irredeemable.

One state stood at the center of this history. Of the roughly 1,500 executions that Americans have carried out since the 1970s, Texas has been responsible for more than 500. Oklahoma actually executed more people per capita during this time, while other states sent more to death row, but when Saturday Night Live sat a smarmy politician atop a stack of prisoners’ coffins, he was a fictional Texas governor, and when a character on The Simpsons played an arcade game called “Escape from Death Row,” she knew she had lost when the machine spouted “The Yellow Rose of Texas” and an executioner, dressed as a cowboy, danced onto the screen.

Texans have relished their reputation for dispensing harsh and efficient justice, amplifying it to guide the country as a whole. Two different Texas governors, running for president in 2000 and 2012, used their death penalty records to appeal to voters in the rest of the country, and the rhetoric trickled down. “If you come to Texas and kill somebody, we will kill you back,” said the comedian Ron White. When anthropologist Robin Conley interviewed members of Houston juries for a 2011 dissertation, one told her, “Down in parts of Texas where I work, we would have a room full of eye-for-an-eye people just wanting to hang this guy.”

The death penalty is the product of democracy.

The criminologist Franklin Zimring drew upon this vision when he wanted to explain a seeming contradiction: How could Americans, especially those with conservative views, profess so much distrust for government, but also support the government’s efforts to execute people? Zimring’s answer was the “mythology of local control.” For many Americans, he explained, executions are “expressions of the will of the community rather than the power of a distant and alien government.” The death penalty, in other words, is the product of democracy: American voters choose the lawmakers who make the death penalty available, they choose the prosecutors who seek the death penalty in individual cases, and then, as jurors, they choose to actually hand out the death sentences. This sense of ownership is what separates us from other countries that frequently impose the punishment, countries that critics like to bring up, like Saudi Arabia, China, and Iran. Their citizens don’t necessarily get to choose whether to have the death penalty, or decide when it should be imposed; we do.

To make such arguments, however, you have to keep one eye closed. Open it and you see a parallel history of American punishment, as present in Texas as anywhere else. Before executions looked like quiet medical procedures, they looked like charred and dismembered corpses, usually of Black men, surrounded by throngs of smiling white faces in the courthouse square. Before the days of seemingly endless appeals, there were the days of no trials at all. A community coming together to exercise its collective will can also look like the powerful violently suppressing the weak. Outside the prison cell where Charlie Brooks waited out his appeals, other Black prisoners were picking cotton just as their enslaved ancestors had done.

_______________________________________

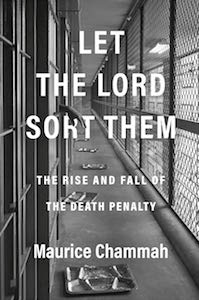

From Let the Lord Sort Them: The Rise and Fall of the Death Penalty by Maurice Chammah. Used with the permission of Crown. Copyright © 2021 by Maurice Chammah.

Maurice Chammah

Maurice Chammah is a journalist and staff writer for The Marshall Project. His reporting on the criminal justice system has been published by The New Yorker, The New York Times, The Atlantic, Esquire, and Mother Jones. He lives in Austin, Texas, where he and his wife Emily Chammah co-organize The Insider Prize, a fiction and essay contest for incarcerated writers sponsored by American Short Fiction.