22 Books That Helped Me Write the Story of My Transition

P. Carl on Inspiration, Imagination, and Identity

As a trans person, I spent most of my life with my head in a book imagining other lives, other bodies, and other histories. In some ways, my memoir is an amalgamation of all the books that kept me curious, kept me thinking it was worth it to keep going. Sometimes it was to dream myself a cowboy on the open prairie, sometimes a soldier with a rifle as tall as me, sometimes a priest giving other men hope of a God on the other side. But reading wasn’t just about imagining myself a man; it was about imagining, period—imagining all parts of my identity until I could physically feel myself as a body alive in the world.

Below is sort of an acknowledgements section to literature and non-fiction and poetry—to the stories that bought me time and helped me to eventually see this body in the context of multiple histories and struggles, to eventually be seen and felt and heard. I owe these works of art, and the many others that I didn’t have room to list, my life.

*

Fyodor Dostoyevsky, The Brothers Karamazov

(Dover Publications)

A novel that tells the story of three brothers and that engages all the major ethical debates—exploring faith, morality, free will, greed, obsession, and madness.

How many times have I read this book? How many times can you read a book this long? I am Ivan, in a constant state of doubt, always on the verge of a nervous breakdown, or not even on the verge. Reading The Brothers K is like being in the psych ward of your own mind—doubt, doubt, doubt, doubt, “I have a longing for life and I go on living in spite of logic.” This is a trans person’s motto. What logic is there living in a constant state of misrecognition? Who wouldn’t, like Ivan, have a nervous breakdown? One time, close to another trip to the psych ward, I rented a cabin in Northern Minnesota and read the novel in three days. Psych ward averted. Hikes, “sticky little leaves as they open in the spring” as Ivan would say, and Dostoyevsky. I went on living.

Charles Dickens, Great Expectations

(Wordsworth Editions)

The coming of age story of an orphan named Pip raised by his not so kind sister, Mrs. Joe and her gentle husband, the blacksmith Joe. Pip, thanks to an unknown benefactor, suddenly has prospects, and thus has a chance to become “uncommon.”

Of course, as the daughter of a used car salesman I wanted nothing more than to become uncommon. Is a used car salesman a comparable trade to a blacksmith? Was my mother my emotional Joe? I didn’t dare fall in love like Pip. There was no Estella but how often, like Pip “did I dream that my expectations were all cancelled?” I read Great Expectations over Christmas break of sixth grade. That Christmas we had tickets to fly to Orlando to go to Disney World. We had never had a family vacation and four days prior my father was arrested for drunk driving, went to jail and then to treatment for thirty days. We spent Christmas in Elkhart—Pip helped me to hang on to my hopes. At the end of the novel we see him walking hand in hand with Estella—maybe, just maybe his love will finally be reciprocated. Maybe, just maybe, his greatest expectation will be realized.

Claudia Rankine, Citizen: An American Lyric

(Graywolf Press)

Rankine has reinvented poetry in form and purpose and Citizen is a masterpiece that exposes in detail our America built at its roots in the violence and cruelty of white supremacy.

I once saw Claudia Rankine described as “the truth” on Twitter. When you read words strung together like this— “You take in things you don’t want all the time. Then the voice in your head silently tells you to take your foot off your throat because just getting along shouldn’t be an ambition.”—the truth seems right. As I went through my gender transition, I had the privilege of working with Claudia on a play about whiteness, and it was impossible to lose track of what I was becoming—a white man. Not just a man, but a white man. I will never be able to stop accounting for what that symbolizes, for the history that my body carries. Claudia’s poetry insists.

Isabel Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns

(Vintage)

The book tells the story of The Great Migration of 1915–1970 of African Americans from the South to the Northeast, Midwest, and West through the lives of three people—a sharecropper’s wife, a farmer, and a doctor.

I read this book when it came out in 2010. I was forty-four years old with a B.A., an M.A. and a PhD. How could I have known so little about this period of history? I felt embarrassed—a gap in my education as wide as the Grand Canyon. “Perhaps the greatest single act of family disruption and heartbreak among black Americans in the twentieth century was the result of the hard choices made by those on either side of the Great Migration.” Wilkerson’s account is staggering, with people’s lives so fully realized that a history book of over five hundred pages reads like a page-turner novel. This book single-handedly changed my understanding of race in contemporary America.

Cormac McCarthy, Blood Meridian: Or The Evening Redness in the West

(Vintage)

It’s hard to summarize this book. An ultra-violent western set in the mid 1800s with no moments of redemption seen through the wanderings of “the kid.”

Sometime in the early part of this century, I decided to read every book by Cormac McCarthy. I am always looking for a way to understand and eradicate my inner rage and violence and reading McCarthy is like earning your PhD in white man’s violence. In those unexpected moments when I resemble my father, unleash on the driver in front of me, say something horrible to my wife, become some version of every bad white man, I think of the kid saying to his friend Sproule, “What’s wrong with you is wrong all the way through you.” What’s wrong with America is wrong all the way through. McCarthy shows us a nation that came into being through violence, a violence that lives in us all.

Jeanette Winterson, Sexing the Cherry

(Grove Press)

The novel is about a mother named Dog Woman who has pockmarks on her face big enough to hold fleas, and her son Jordan, who adores her. It is a fairytale that subverts male power and questions the dichotomy of gender roles.

Jeanette Winterson’s writing has been a life raft for queer people for more than thirty years. She was thinking about “non-binary” as a gender possibility long before it became a recognized gender marker. Sexing the Cherry became the basis for one of the chapters of my doctoral dissertation as I compared Women’s Studies and Queer Theory, as I considered if borders around gender constituted a more powerful way to make political change or if the fluidity of “queer” was more inclusive, more politically savvy. “Was I searching for a dancer whose name I did not know or was I searching for the dancing part of myself,” asks Dog Woman. Sexing the Cherry helped me to keep the dancing part of myself within reach.

Ernest Hemingway, A Farewell to Arms

(Scribner Book Company)

A love story between an American paramedic serving in the Italian Army, Frederic Henry, and an English nurse, Catherine Barkley. They meet near the Italian front where the Italians are eventually defeated and Frederic and Catherine flee to Switzerland before Frederic is executed in a purge of soldiers blamed for losing the battle.

In 1990 when I was doing my Master’s in Peace Studies at the University of Notre Dame, my colleagues were studying things like international law, conflict resolution, and nonviolent resistance. I created my own path reading war literature: War and Peace, Mother Courage, and A Farewell to Arms. It was perhaps A Farewell to Arms that turned me most resolutely against war and the men who orchestrated it. I loved Frederic, his quiet devotion to both Catherine and the cause and the mere thought that he would be held accountable for the Italians poor military strategy demonstrated the emptiness of words like conviction and loyalty when it came to men and their weapons. The following summer I would get arrested for trespassing on government property while protesting at a naval nuclear weapons base in Southern California.

Zora Neale Hurston, Their Eyes Were Watching God

(Harper Perennial)

This is the story of Janie Crawford, in her forties, retelling the story of her life to a friend, mostly an account of her relationships with various men, who treat her like property, a “mule,” until she meets her true love Tea Cake.

I read this book in 1991, when I was working in Deland, Florida, with the children of Mexican union farmworkers. The novel takes place in Florida, partly in Eatonville, not too far from Deland. I read all of Hurston that year, determined to understand why her writing was dismissed by the authors of the Harlem Renaissance. Why had it taken almost forty years to recognize her genius when she began to be read in BlacStudies programs in the 70s and 80s. My work in Deland spiraled me into a deep depression—the poverty, the danger these young people faced, the lack of opportunity. Hurston’s rich language, her ability to capture the nothingness of Central Florida, and Janie’s perseverance, as African-American men objectified her the way white men objectified them, mirrored my sense of objectification by the Catholic church, my employer at the time. I am not equating my plight as a white women with Janie’s, only acknowledging my gratitude to Hurston for writing so powerfully about the relentless reality of patriarchy and Janie’s refusal to give up hope.

Judith Butler, Gender Trouble

(Routledge)

Perhaps the most important book to upend all the preconceived tenets of feminism that had come prior, arguing against identity politics contending both sex and gender are cultural constructs, performances etched in the body.

I started my PhD in the fall of 1991 in Cultural Studies and this book was my Bible. I bought a pair of men’s black jeans, a blue denim men’s shirt, and a blue flower tie and delivered my first academic lecture on the movie Thelma and Louise and its subversion of what constituted women’s behavior, Butler leading the way. Gender Trouble denies the “before” within feminist theory and therefore any notion of an “authentic feminine.” Gun toting Thelma and Louise were my anti-feminine heroes while I began to rethink the possibilities for my own body.

Doris Kearns Goodwin, Lyndon Johnson and the American Dream

(St. Martin’s Griffin)

This is a heartfelt biography of Lyndon Johnson.

I read this book for the first time two years ago. I owe it the biggest insight I’ve had to date on what is at the heart of white masculinity—conviction. In fact, Johnson refused to end the Vietnam War because of his own conviction, and despite the advice of almost all of the experts surrounding him. We all know where that conviction got us.

Jenny Erpenbeck (trans. Susan Bernofsky), Go, Went, Gone

(New Directions Publishing)

This book tells the story of Richard, a retired German professor of the classics who slowly becomes deeply involved in the lives of a group of African refugees in Berlin.

Richard wonders, “How many times … must a person relearn everything he knows, rediscovering it over and over… Is a human lifetime long enough?” I have spent my lifetime trying to understand “otherness.” I am on the top of everyone’s list when they need someone to sit on a panel or committee about “diversity.” I am a go-to “other.” This book, layer by layer, exposed to me the impossibility of inhabiting a body that is not mine, feeling a culture that is not mine, helping in circumstances that exist miles away from my own experience. As ridiculous as talk of border walls is, committing to connect across difference is a lifetime’s work. Borders live in all of us.

Elizabeth Strout, My Name is Lucy Barton

(Random House)

A novel about a mother and daughter reconnecting to one another.

As Lucy is recovering from an infection in the hospital, she says, “It was the sound of my mother’s voice I most wanted; what she said didn’t matter.” It was this very sound I thought might save me at numerous points in my life. This is a book about everything left unsaid, the book that forced me to say I would have to relinquish the hope of reconnecting to my mother.

Rebecca Solnit, A Field Guide to Getting Lost

(Penguin)

A meditation on all the ways to get lost and all the emotions that come in those moments when we aren’t quite certain where we are.

“To what degree has anxiety replaced optimism,” Solnit asks as she considers the early explorers and the optimistic way they approached the unknown, the possibility of what they might find. This book is my most popular teaching tool, as the majority of my students are crippled by anxiety, obsessed with finding their way in a direct shot from point A to point B. I get it. I have been no less influenced by a culture that insists we know where we are headed. This book was my meditation tool during my gender transition. I had no idea where I was going or where I would end up. “Never to get lost is not to live…” I have a done a lot living in the last few years.

Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow

(New Press)

An account of the mass incarceration of African-American men and the subsequent creation of a new caste system that uses the legal system to keep black men as second-class citizens who, as a result of either being locked up or having criminal records, are denied basic civil rights including the right to vote, the right to serve on juries, and the right to attain affordable housing.

I read this book when it came out in 2010. I was working in a theater in Chicago as the Director of Artistic Development and planning what would be the following season. We planned a season based on the theme of race. All five plays selected were about race–and all five were written by white men. I couldn’t take in what The New Jim Crow was exposing and defend that season. Thanks to that book, I quit my job at the theater.

Heléne Cixous, Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing

(Columbia University Press)

This is a book about writing that explores three necessary “schools” for great writing to be possible: The School of the Dead, The School of Dreams, and The School of Roots.

I have been reading and teaching this book for years. It scares me. “It is the feeling of secret we become acquainted with when we dream, that is what makes us enjoy and at the same time fear dreaming.” To write is to dream. To write is to risk everything, to bring what is buried to the surface. I had to read this book perhaps five times as I wrote my memoir, to say out loud what I had kept hidden from myself, to tell you secrets that I swore I would not remember.

Lynette D’Amico, Road Trip

(Twelve Winters Press)

This is a novella about two friends who travel across Minnesota and Wisconsin together, veering off track more than once.

This is my wife’s novella. I have been reading her writing for twenty-two years. When we were first introduced, I was told she was a writer and I knew immediately I could not date someone who was just “okay” at telling stories, so I tracked down one of her essays “Home Movies.” It was hilarious and beautifully written and we started dating. Lynette has been my partner in all things creative for twenty-two years, and Road Trip is a perfect example of Lynette’s imagination and talent. I wouldn’t be a writer if it wasn’t for her, for us.

J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings

(Del Rey Books)

A fantasy trilogy that includes The Fellowship of the Ring, The Two Towers, and The Return of the King. It is about the search for a ring that has the power to rule the world.

The summer after seventh grade was, in Dickensian terms “the best of times and the worst of times.” I had been kicked out of Catholic school and was going to start eighth grade in the public school. I had put on weight, a fleshy blob whose clothes suddenly didn’t fit. I had no friends. But The Lord of the Rings saved me from complete misery. I laid on our worn green couch next to the big tear in our worn green carpet in the living room and I read all three books of the trilogy—1,241 pages plus The Hobbit, another 304 pages. I almost never looked up. I walked the entire distance of Middle Earth in my imagination. Elkhart, Indiana? Where was that?

Denis Johnson, Jesus’ Son

(Picador)

A linked short story collection about the travels of a drug addicted hitchhiker named Fuckhead.

I have never had an issue with drugs. I don’t relate to Fuckhead’s addictions. I just loved the utter chaos of this book, its structure and language. “With each step my heart broke for the person I would never find, the person who would love me.” Growing up in a house of abuse and neglect, I never felt I could be loved. I couldn’t feel love. I still struggle to feel love. This is what Fuckhead and I had in common. The hole in the soul of the addict is much like the hole in the soul of someone abused.

Tony Kushner, Angels in America

(Theatre Communications Group)

A two-part play about AIDS and homosexuality and politics and power.

This remarkable and epic piece of storytelling has many pieces that drew me to it, but I hold onto it almost thirty years after its premiere because it is such a profound lesson about bodies—their secretions and wounds and sexual preferences. Louis is a character who is all head and politics and when his lover’s body begins to ooze and decay, he walks away. His terror of the flesh is my terror.

Maggie Nelson, Bluets

(Wave Books)

A prose poem about all things blue.

“Nonetheless, as Billie Holiday knew, it remains the case that to see blue in deeper and deeper saturation is eventually to move toward darkness.” I love this little cultish book, the blue of despair, loss, depression, and loneliness sitting side by side with the beautiful blue of the sea and sky. The roaming of a life in relationship to a color, my favorite color. Nelson’s writing lets me be sad and soothed, hopeful and despairing.

Teju Cole, Open City

(Random House)

A character, Julius, wanders through New York.

I have always liked that word peregrinations, and the prose of this stream of consciousness novel defines what it means. This is a book about walking, walking without purpose or regulations. Its language is a kind of improvisation. I read it when I was walking every morning with my wife in a cemetery in Boston, trying to get up the courage to walk away from something I thought I might do forever. “To be alive it seemed to me, as I stood there in all kinds of sorrow, was to be both original and reflection, and to be dead was to be split off, to be reflection alone.” Toxic masculinity had poisoned my workplace. I felt dead for sixty hours a week relegated to someone else’s reflection, but peregrinations through cemeteries, arboretums, and white mountains brought me back to my original half.

Elizabeth Kolbert, The Sixth Extinction

(Picador)

A book that argues we are in the Sixth Extinction, in a state of dire environmental decline marked by the disappearance of native species at an unprecedented rate.

This book presents us with the biggest danger facing our planet. Kolbert tells it in a way that’s easy to follow. It’s a book that should make us drop everything we are doing and commit ourselves to our survival as a species through environmental activism. What gender I am won’t matter when humans no longer exist. I once heard Kolbert lecture. She began by saying, “When I am finished, the first thing you will want to ask me is—what should I do?—I am going to tell you now, I don’t know.” When she finished her lecture, a man immediately raised his hand and said, “So, what should we do?” This book is like a persistent echo in the back of my mind: What should I do? What should I do? What should I do?

__________________________________

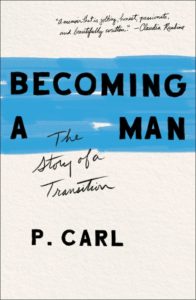

From Becoming a Man: The Story of a Transition by P. Carl, which is now available in paperback. Used with the permission of Simon & Schuster. Copyright © 2021 by P. Carl.