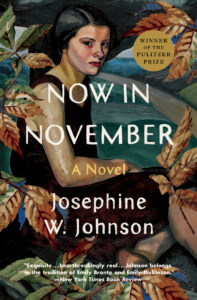

“A Book About Thirst.” In Praise of Josephine Johnson’s 1934 Pulitzer Prize-Winning Novel

Ash Davidson on Now in November

Quiet and surprising, Josephine Johnson’s Now in November is more than a novel about the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl. This is a book about thirst—the land’s thirst for rain, yes, but also human thirsts for love, for justice, for the relative security a little money can bring.

These longings start with Arnold Haldmarne, who is already deep into his fifties when, broke and “chopped back down to root,” he sells the family car and most of their possessions and moves his wife, Willa, and three daughters to a heavily mortgaged farm. There, he takes up the plow, yoking the family to a debt that will cast its shadow over their lives.

Deep-feeling, observant Marget and her little sister, Merle, quickly fall head over heels for the place. Free to roam, the younger Haldmarne girls delight in the natural world and accept their roles cooking and cleaning. Only the eldest, Kerrin, who has inherited their father’s short temper along with his red hair, balks. Volatile and restless, Kerrin doesn’t fit in the family she was born into, and her bouts of depression and defiance of her bitter, overworked father frighten her sisters. But ultimately, it’s the arrival of a hired hand, Grant, worldly, kind—and available—that reveals deeper thirsts.

In a parallel universe, Now in November , which sold out its first edition five days before it was published and won Josephine W. Johnson the Pulitzer Prize in the Novel in 1935, at the age of twenty-four—the youngest person ever to win a Pulitzer for fiction (only twenty-two women have won it in the nearly nine decades since)—would be shelved companionably alongside The Grapes of Wrath. Instead, this slim, tender, and sometimes brutal novel has, like its author, largely slipped through the literary cracks. If you’ve never heard of Now in November or Johnson, you’re not alone. Yet, for a book published almost ninety years ago, its concerns still feel surprisingly modern.

If you’ve ever struggled to make the minimum payment on a credit card or student loan, you’ll recognize how the corrosive worry about money gnaws at the Haldmarnes. A failed dairy strike exposes the rot at the core: the injustice of working hard and just barely scraping by, of subsisting at the mercy of the market and the whims of the weather. The thirst for a fair price for the fruits of their labor taunts the parched family like a mirage, disappearing as they draw close.

It wouldn’t take much—one good season—to lift the Haldmarnes out of their poverty and elevate them to the relative comfort of their neighbors to the north, the Rathmans. They are, after all, privileged compared to their Black neighbors to the south, the Ramseys.

The Ramseys are warmhearted and generous, and Marget, our eyes and ears in the novel, is matter-of-fact about the brutality of American racism; her father would happily borrow the Ramseys’ mules, but won’t break bread with them. This racism robs the Ramseys of agency, so that at times they seem less like people and more like symbols of the perils of being both poor and Black in America.

This is the same America that loves a good bootstrapper success story, but this trope Johnson sidesteps, focusing instead on the precariousness of working-class life, when a slip, a fall, a burn, or a broken bone can begin a slow slide, the way the cost of medical care and absence of a social safety net still sink working people today. The shame of watching others suffer without being able to help weighs heavily.

This is the same America that loves a good bootstrapper success story, but this trope Johnson sidesteps, focusing instead on the precariousness of working-class life, when a slip, a fall, a burn, or a broken bone can begin a slow slide.The seeds of Johnson’s later activism—and future books—seem already sowed in Now in November, from labor rights to feminism to the environment. After her Pulitzer win, she told the New York Times, “My uncle is a dairy farmer . . . The land around him is farmed by tenants or share croppers. Their condition is almost hopeless under the present system.” A year later, Johnson was arrested in Arkansas for encouraging cotton-field workers to strike. In 1969, she penned an op-ed for the Times, railing against environmental destruction, and published The Inland Island, perhaps her best-known work, now cited as an early stepping-stone in environmental literature.

In many ways, the drought and devastation of the Dust Bowl in Now in November rhyme with our modern experiences of climate change, when a tipped electric line can send a tidal wave of flames surging across the landscape, licking hundreds of homes from the map.

Yet for all the big issues it tackles—from race to class to gender, from mental illness to the inhumanity of industrialization—the book’s most artful and revelatory moments often come when Marget, attuned to the slightest change in barometric pressure, turns her gaze on the family’s emotional weather. “I wanted to give a beautiful and yet not incongruous form to the ordinary living of life,” Johnson told the Times.

As ponds dry up, crops wither in the fields, calves cry out for water, and the family searches the sky for rain, the yearnings that have been smoldering since Grant’s arrival begin to flare. Kerrin becomes increasingly desperate in her pursuit of him, but Grant’s affections have landed on Merle, who doesn’t return them. As she watches from the sidelines, it’s Marget’s sensitivity to Grant’s heartache, and her own secret, unrequited love for him that form the beating heart of the book.

Timid and plain, Marget is accustomed to hiding her feelings and reining in her hopes. As the middle sister, she knows her place, sandwiched between clever, self-confident Merle, who charms and teases Grant with her banter, and beautiful, unstable Kerrin, who brazenly reaches for what Marget desires. Marget’s own great strength is acceptance. When all the violence and tragedy unspool in the novel’s final pages, she simply bears it.

To absorb the true power and beauty of Now in November, it helps to read the book through to its blazing end and then loop back to the opening chapters. After the smoke has cleared, you can walk alongside Marget again, looking back on the last ten years with the magnifying glass of hindsight, bearing the full weight of the past, as she does.

___________________________________

Excerpted from Now in November: A Novel by Josephine Johnson. Introduction copyright © 2022 by Ash Davidson with permission by Scribner, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.