He came into the shop with a pitifully small amount of cheap candy to sell. The men gruffly refused to buy or to even look at his wares, and he shuffled toward the door with such a forlorn air that the young lady called him back. She was smiling partly because she liked to smile, and did so whenever fate gave her a chance, and partly to put the tattered little hunch-back at his ease.

The boy approached the table where the girl sat with the air of a homeless dog who hopes that he has found a friend.

“Let me see your candy, little boy.” She toyed with the paper-wrapped packages for a while. She knew that she would buy one even though she had but fifteen cents in her pocket-book and a very vague notion as to where her next week’s rent would come from. The hunched-back boy looked too dejected to turn away, however. She handed him a nickel.

“Thank yuh ma’am,” said the boy. “You certainly is a nice lady. You aint mean lak some folks.”

“Thank you,” rejoined the girl, “and where do you live?”

“I lives down in Fifty-Third Street. My mama, she dead when I wuz a baby an’ my fadder, too, he dead.”

“Who takes care of you?”

“My grand’ma, an’ she teached me th’ Lawd’s prayer an’ I goes tuh Sunday school when I got shoes. See this coat? Aint it nice? A lady gave it to me.”

“It is a pretty coat,” agreed the young woman, “and do you belong to the church yet?”

“Naw, not yet, but I guess I will some day. A lady that used to live wid us she got religion, but after a while her sins come back on her. Do you know my teacher?”

“No, I don’t. What does she teach you?”

“She, she teach me how to read and count a hundred, but I forgot what comes after ninety-seven. Do you know? Let’s see, ninety-five, ninety-six, ninety-seven—gee. I can’t learn that.”

“Of course,” laughed the girl, “ninety-eight, ninety-nine, one hundred. What else does she teach you?”

“She say when I go to Heben I be white as snow an’ the angels goin’ to take this lump out of my back an’ make me tall. I guess maybe they roll something over my back like dat machine, what dey rolls out the street wid.”

The girl felt very much like laughing at this original idea, but seeing his serious face she resisted and asked him very kindly how old he was.

“Let’s see,” answered the boy. “Grand’ma she say I’m fifteen, teacher she say I’m sixteen. I guess I’m sixteen cause once, long time ago, I wuz fifteen before.”

The young lady exhibited signs of flagging interest and asked no more questions but the boy showed no inclination to go. His eyes never left her face, and at last he asked, “Where is yo’ mama and papa?”

“Both dead.”

“Who takes keer of you, then?”

“Why, I do, myself.”

“Nobody buys you nothin’ to eat, neither?”

“No.”

The hunch-back looked pitying at the girl, at himself, at the floor, and at last said in a voice full of pity, “I guess maybe I can put on some long pants an’ marry you an’ then I’ll buy you some- thing to eat.”

The girl would have laughed but the world of sympathy, understanding, and fellowship that showed in the boy’s face and choked his voice restrained her. How often had she sought that same understanding fellowship within her own class, but how seldom had she found it!

“Well, lady, I’m goin’ now cause I got to make a fire in the stove for Grand’ma. But I come back again some time cause youse a nice lady. Maybe I bring you some Easter candy if I have some nickels—that’s the day the Jews nailed Jesus in a box an’ put rocks on it, but he got out—ask the Bible, he knows.”

__________________________________

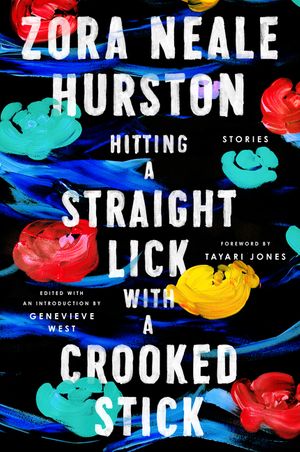

Excerpt from Hitting a Straight Lick with a Crooked Stick: Stories from the Harlem Renaissance by Zora Neale Hurston. Published by Amistad Press. Copyright © 2020 by the Zora Neale Hurston Trust.