A Beautiful Sadness: On the People and Places That Will Forever Haunt Us

Hanna Lillith Assadi Tells the Story of Her Grandmother’s Life

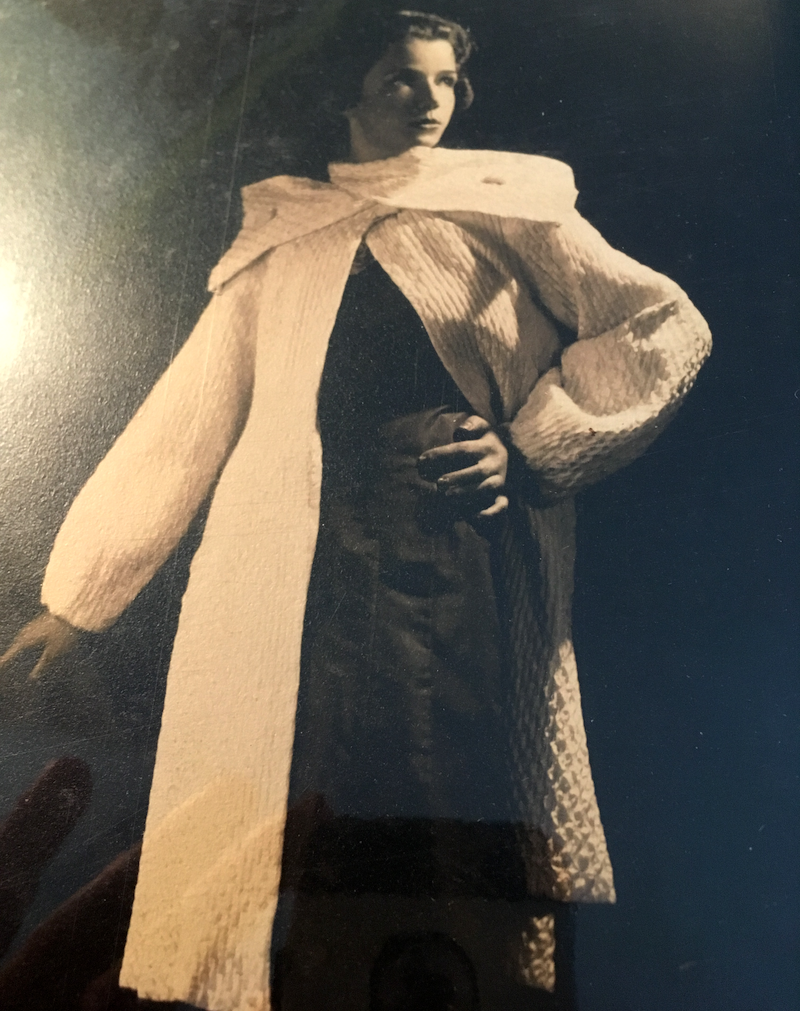

Haunted. That’s what those who knew my grandmother, Anne, say about her. Beautiful, but never happy. She died when I was too young to remember her but I love looking at photographs of her. She looks like someone who is missing something. She was very beautiful, in a vintage Hollywood way, and very sad. No other collision of adjectives captivates me more.

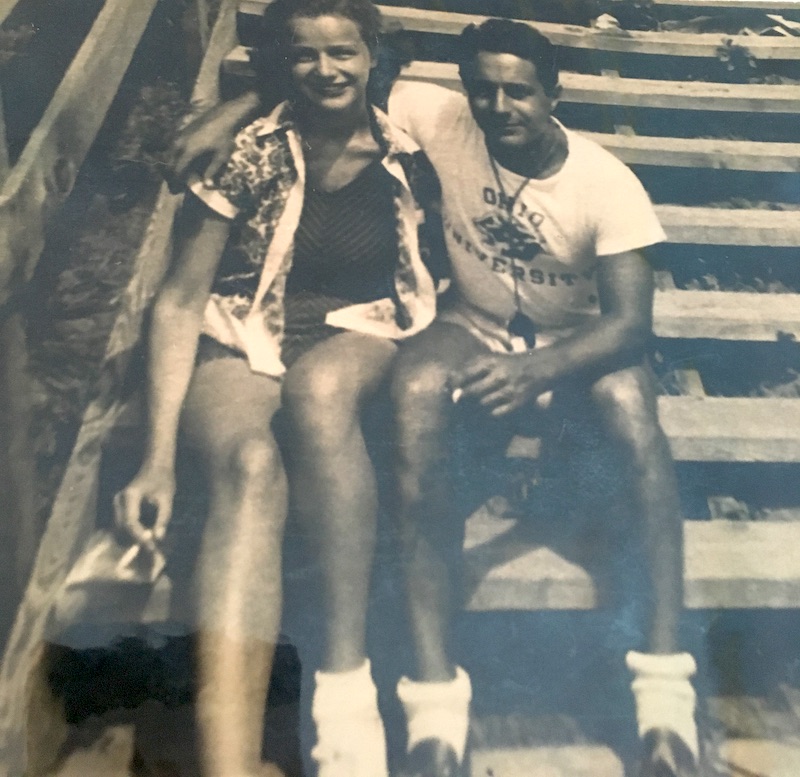

There are the haunted images, the ones from later in her life, but then there is that image of her from her youth, from the time before she married my grandfather, from the time when she was still poor and it appears, still happy. She’s with a stud in the Ohio University t-shirt. They’re both smoking and she’s smiling for the camera, a big, stupid, can’t be helped, smile of a girl in love. Their thighs touch. You know what they’ve done and how it felt.

This photo makes me want it all back too, that raw, wild desire of first love. Or is it true love? The feeling of 17. I wonder what became of Ohio University. Don’t each of us know his face, a face like his, our own version of his face? The face that asks us that excruciating question: What if?

This boyfriend was not my grandfather Seymour. Anne’s family was bankrupt, nearly destitute. These were the years of the Great Depression. A woman had to be practical in her day (doesn’t a woman still?). It was for Seymour she would leave New York City for Florala, Alabama. It was with Seymour she would become a millionaire.

At 17, Seymour was sent away from New York to run a Southern branch of his father’s Manhattan-based textile factory. A style called “Western” shirts was the source of my grandfather’s fortune (a fortune that would pass away with him). But at 17, Seymour had also fallen in love. It is rumored that my grandfather, a trained musician with a “sensitive” disposition, was actually sent to Alabama to be kept far apart from his male mentor, a pianist. Unlike Anne’s Ohio University guy, I don’t have a photo of my grandfather’s might-have been lover. There is no evidence their love ever was.

Perhaps 17 broke them both, each in their own way. But then Anne and Seymour found one another. And here I am floating in mid-air, Anne concluded in a letter she wrote her future husband from New York on the occasion of their engagement. Yes, back then, back there, Anne was happy.

*

So, when did it begin? I wonder, Anne’s beautiful sadness? Did it begin when she discovered my grandfather’s preference for men? Or did it begin earlier, when she first arrived in Florala? Florala is haunted too, after all. Just north of the Florida border, it belongs to the gothic South, dressed in the warm and mournful, bloodied music of that latitude. The land is pastoral, movingly green; the light, golden in the summer and sepia in the winter. Kudzu and moss cascade across the spectral town, a lake shimmers there between the trees named after the President also known as the “Indian Killer.” Confederate flags are still wretchedly hung.

My mother says that Anne just always missed New York. Here I am back in Anne’s city, my own city, and my daughter’s city, too—we were all born here—and all the leaves are dead. It’s December, nearly the solstice, mid-afternoon, and look, its already evening time. I can’t stand the darkness. Or is it the cold? Whereas when I was away, I constantly said, I miss the winter.

A man in a pink jumpsuit lies overdosed in the street. The wind does its thing with the raspy trees and the nannies on the playground gaze longingly into their phones and my own bright child, this evanescent angel, scrambles up and down the smelly, wet slide at the playground, but I am not looking at her. Life is happening for the very last time right before me and I’m looking askance at the sallow sky. I hear them everywhere, the sirens. We’re all wearing masks again.

Do I detest this city or is something else the matter? Something I can’t look at directly. Something deeper than a geographic malaise. I’ve come back to the same coordinate in space, but not in time. When did it begin for me? This beautiful sadness.

*

By 1964, Anne no longer felt like she was floating in mid-air. She wrote to Seymour often of leaving the narrow confines of Florala for the larger world… of seeing New York, her hometown again. She too believed her pain was geographic. All she needed was to hear the roaring music of her city. She could just wander off into it, back into Ohio University’s arms. But of course, it wouldn’t be there for her anymore, that city, the one she left behind. It never is. Besides, she was no longer 17; she would never be 17 again.

Sometimes I think you married Florala and the factory, not me.

At the time, my grandfather was still the king of that town. He employed nearly all of its citizens. He even built a hospital there. It is not hyperbole to say that everyone knew his name. Now the trees on the property that once belonged to him have been torn down, the hospital is defunct, the factory insignia rewritten in ghost-hand. Was it Florala or the person he was when he arrived in it that fastened itself so permanently to my grandfather’s heart?

I arrived in New York broken, too. And came back and came back, broken again. So many landings at JFK, weeping against the icy plane window, relieved, terrified, electric with longing. Sometimes I wonder: am I more that girl than I am myself? Are we prisoners to places or to the people we once were in those places?

*

Occasionally, my grandfather relented. He would never leave Florala permanently. No, not even when it was too late for him. He would die there. But back then, he traveled with Anne from time to time. To London, to Paris, yes, to New York. This was all before his business wandered across the Pacific. They shopped at Henri Bendel. Anne was given gems, a mink fur. They stayed at the Plaza Hotel.

But by the 70s, changes in the kingdom were already afoot. My grandfather wouldn’t move the factory overseas, vehemently opposed all advice telling him to do so. He was a gay, Jewish New Yorker, a pianist who once met Rachmaninoff, who wanted to keep America great by keeping jobs at home in the deep, red South. But it didn’t matter what he wanted. The dollar abides by its one true law: to multiply for those who possess the most of it.

But first, before the business was gone, right there wandering down the Avenue on one of those trips back home to New York, Seymour lost Anne. Back in her city at last, she wandered away from him for the first time. This was before the Alzheimer’s diagnosis. This was its first sign. I wonder what it was she hallucinated in those once familiar streets that compelled her to leave her husband’s side?

I left New York City too, and only now upon returning to it, do I realize how haunted it is. It is only in these streets, strolling my daughter along, that I still see the face of my dead ex in so many brilliantly dressed, vaguely high, European-looking men. And only here that I see myself still in the dark, weepy eyes of so many smoking girls outside of bars, so young, maybe even 17, waiting for that fucking guy, the one I miserably, movingly loved too, to crash down into their night. Maybe I live inside them more than I do my own self, this body meandering through a city I once called my own, called my home. But no, we can never go back, not in time, not in space. It’s me, I’m the haunted one. Not New York.

*

I can’t believe this terrible loss of my thinking, Anne wrote later, back in Florala, after the diagnosis. I know that you have been douging as much as you can to ambiate the pain of the unknown of my loss—I thank you for all you try to help me in this dreadful loss. Her descent was slow and then quick. She died in 1988, the same year the factory was shuttered and the business lost. Such is the irony of life, that everything Seymour had made in Florala passed away with his wife, who resented it most.

I find myself repeating questions: such as—”what time is it?”

*

I have always written because of time. To stop it. It began that way, even before I’m 17 and heartbroken, or in love again—there’s a full moon and the night is fragrant with honeysuckle and he’s carrying me in his arms and that gold necklace shimmers against his tan skin. I will never feel so alive again; it’s amazing, terrible that this night will die. Beauty lives right beside death. So, I wrote to go back in time, see around the end. Cheat myself into believing I could cheat it.

Anne wrote too. And then didn’t any longer. Maybe Alzheimer’s offered her a similar passage. A superior one. Maybe in the end, in our ultimate defeat, we do learn how to move against time. Let us go now back to the land of 17 and there he is in that Ohio University t-shirt which still smells of him, and you’ll smile that big, stupid, can’t be helped smile. You’re in love. Now it’s forever.

_________________________________________

Hannah Lillith Assadi’s The Stars Are Not Yet Bells is out now.