Look, Think, Share with Friends: Bea Setton Breaks Down Her Writing Process

In Conversation with Brad Listi on Otherppl

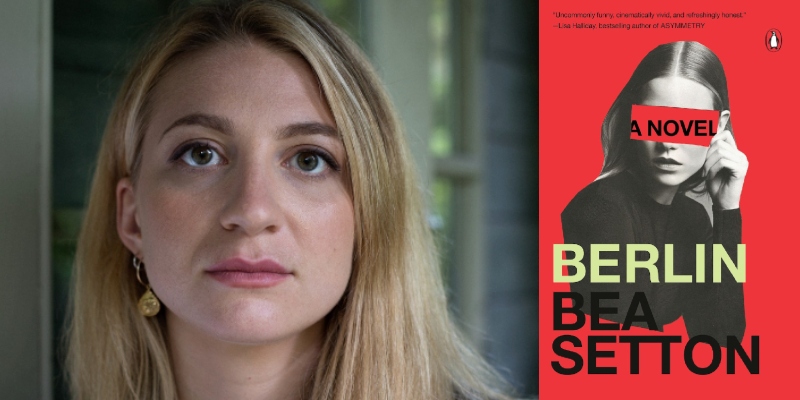

Bea Setton is the guest. Her debut novel, Berlin, is out now from Penguin Books.

Subscribe and download the episode, wherever you get your podcasts!

From the episode:

Brad Listi: To go back to this recurring phrase of how sharply observed this book is, you wrote a piece, I believe for Shondaland, where you broke down your method, which I don’t see very often. I wish I saw it more from writers. It would make for interesting conversation. But you talk about a kind of step by step process. And obviously this isn’t the entire thing, but it is something very related to how sharply observed this book is.

Another thing I kept saying to myself is like, Wow, Bea can write about anything and make it interesting. It doesn’t even have to be something super kinetic or sensational for me to be leaning in. She could be talking about the kitchen or what somebody’s having for breakfast. You’re very good at observing and finding new meanings in things that might not be immediately evident.

And then I read this piece in Shondaland where you’re breaking it down. And it makes it all kind of click into focus how you did it. For the benefit of listeners, let’s just go through this real quick. The first thing you advise people to do, if they wanted to follow your method, is you say, “Look at the thing you’re trying to describe. Really look.” So this isn’t a superficial looking. This is a deep looking.

Bea Setton: Yeah, really look at what’s in front of you. That’s seems straightforward, but it’s hard because we’re all so distracted. It takes a kind of discipline.

Brad Listi: And that’s also tied to what you were saying earlier about your philosophy training, where you spend five pages breaking down something that the ordinary person would spend five seconds breaking down. You have to kind of force yourself to keep sitting there and to keep looking and to keep thinking about it.

Bea Setton: Yeah. And stay with it. Be patient.

Brad Listi: So, number two, “Let your mind make all kinds of associations.”

Bea Setton: Yeah. The best descriptions for things are often things that are not directly related to the thing in front of you, and they kind of convey them better. One thing that I often think about is the idea of a moon—which is the example I gave in the essay—is like a knuckle. It’s not something we might ordinarily think, but for me it really works in terms of how white the moon can look, and it can look like the knuckle of a gripped hand. That’s not an ordinary association.

And so it’s that kind of thing where you really liberate your thoughts to make all kinds of associations that are not in the realm of the moon. Because we all know certain things that are associated with the moon. It’s always seen as something feminine, something beautiful, and those qualities might work, but I think it’s really disassociating from the common phrases around the thing you’re trying to describe to really see it afresh.

Brad Listi: Got it. And then the third thing is, you say simultaneously, try to think about the atmosphere you’re working to create. So if you’re looking at a thing, and you’re really looking at it, and you are making all kinds of associations, it’s not enough to just make all these associations and pick one. You’re saying that you have to also consider context, like what is the story you’re telling? What is the setting of the story? What is the atmosphere and the mood and the tone of the thing that you’re trying to create? And then how might you land on an association that best fits into that tapestry?

Bea Setton: Right. Let’s say you have a window, and you can see the darkness outside. You could see it as like—this is not good—but it could be a gasping darkness, or expelling something. Or you could see the window as giving shape to the darkness. And those two things both kind of work, but they’re very different in terms of that the first one is quite scary and the second one you’re implying something more cozy and familiar.

So obviously having the free associations is great, but then you have to be aware of the effects that you’re going to have. It can be super jarring if you read quite like a gothic description of a sunset, if it’s described as bloody in a super romantic context. That might work, but it doesn’t make sense here. And so also being attuned to the atmosphere that you’re trying to create. I think a lot of people do this naturally.

Brad Listi: The fourth thing is you say, “Write metaphorically and send it to your friends.” What do you mean by write metaphorically?

Bea Setton: I think that is the short and condensed version of saying, write the metaphor. I think people know what metaphoric writing means. It’s like stuff in poetry and stuff that there’s usually too much of in a lot of text. I have like four metaphors a page sometimes, and I’m like, This is too much. That’s what I mean by write metaphorically—don’t hesitate to over-embroider the language, especially at the beginning, and to use many, many adjectives, especially in that first part. And then you can pare it down.

The way I often think about it with metaphors or descriptions is like, you know when you’re trying to hang up a picture on a wall, and you have a hammer and a nail, and you’re looking for where you can put the hammer in, you have to go all over the wall in order to get to the hollow point. And so in terms of words, I say the same thing. Throw loads of words at the wall and one of them will hang correct. That’s what I meant in terms of metaphors.

Brad Listi: And this idea of sharing with friends—I just talked with Samantha Irby on this show not too long ago, and I was getting into how she does it. She’s a very funny writer and writes these personal essays that are super candid, and she has this great conversational voice on the page, in a way that is not entirely dissimilar to Daphne, your heroine or your anti-heroine.

One of the things Samantha Irby said, which sort of squares with how you wrote your book, is that she keeps a friend in mind as she’s writing, and she writes it as if she were telling her good friend a story. And it has to meet that standard. Like if I were telling this story to my best friend—or in your case, a collection of best friends, you have a whole group that you’re sending this thing to.

That to me seems like a really practical, useful, intelligent way to hone your narrative capability. That is what we should be doing, right? You want to treat the ultimate reader of your book like a friend. You hope to connect somehow on that level. There’s an intimacy between writer and reader, especially when there’s a good connection, when the work is really speaking to the reader, and maybe in particular when it’s written in the first person, you really do feel like, Wow, this person’s just talking to me.

I think that’s something that maybe is easy to get away from, but it’s a useful kind of North Star. What if I were telling this to my best friend? How would I keep them entertained? What would I have to say to cause them to lean in as opposed to rolling their eyes or whatever your best friend would do if you were failing to meet the mark.

Bea Setton: Totally. I mean, I think especially when it comes to things like if you’re thinking of writing something metaphoric, it has to be comprehensible. And I’m like, if my friend cannot understand it in a text, then it’s too complex or it’s not right, and I need to change it. I have that standard with writing because for me the most important thing in my writing is that it be entertaining. I would like it also to be true in some way, but mainly I want it to give people pleasure, and I know how beleaguered people are in terms of things competing for their attention span.

And so for me, in terms of sharing it with my friends, who are not necessarily literary people who spend a lot of time reading, it’s like, do they get it immediately? If not, I haven’t been precise enough or I haven’t captured the essence in a way that’s universally relatable and I need to rework it. It’s also that standard of are they getting it straight away in a short amount of time? If not, I rework it.

*

Bea Setton was born in Paris to Franco-British parents and has lived in the US, Colombia, Belgium, Germany, and the UK. Currently residing in London, Setton holds an MPhil in Philosophy and Theology from Cambridge University and gives her time mentoring for Black Girls Writers. Her critical and creative writing has started popping up in popular outlets such as The Irish Times and Female First.