My Mother the Inventor: Why “Fail Better” is Sometimes the Best Lesson a Parent Can Give

Coco McCracken on Her Mother’s Past as an Inventor—And What It Taught Her About Being a Writer

My mother was an inventor. This is a sentence that I rarely utter aloud because it feels so bold and rare, which she was. But it is an accurate descriptor, even if the truth is that she technically only saw one product into the market and it failed spectacularly, bringing thousands upon thousands of dollars of debt into our lives and arguably taking down my parents’ marriage at the same time.

It’s a difficult topic to say the least, largely because of how embroiled her “inventor” phase is with our family’s divorce, her drinking problem, and thus, the lowest point of my childhood. So, for most of my life, I chose to ignore the exciting title and regarded her venture as a fruitless phase for a bored housewife. But last summer, I drove to Toronto to help my family go through some boxes of old things, and what I found there changed my perspective about my mother’s work—and my own as a writer.

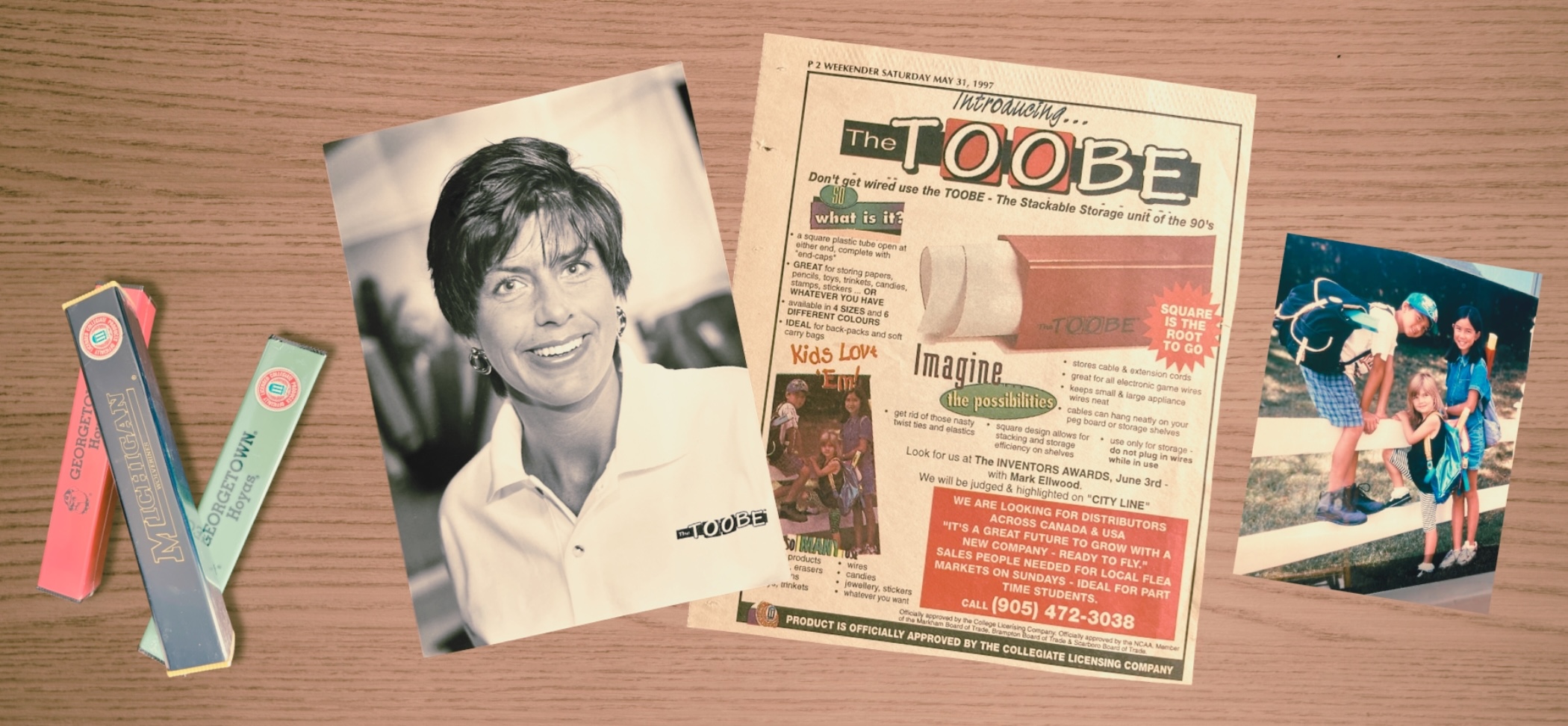

Business headshot of my mom, Lesley-Ann, beside a clipping of her first ad.

Business headshot of my mom, Lesley-Ann, beside a clipping of her first ad.

Mom’s invention was called the Toobe. Even though the Toobe—pronounced “TUBE”—seemed like a simple name, most people called it the “Tubey.” Mom immediately turned that hiccup into her slogan. To be or not Too-be—it’s whatever you want it to be. It was a very simple, elongated storage tube made of durable plastic, except it had squared edges instead of rounded. That’s it. Some models had caps on the ends for smaller things like pens. But Toobes were mostly for cords, papers, and larger objects for people who were architects, contractors, etc. The uses were truly endless (at least in the 1990s). She gave them to all my friends, and we carried our homework and markers in them all through elementary school.

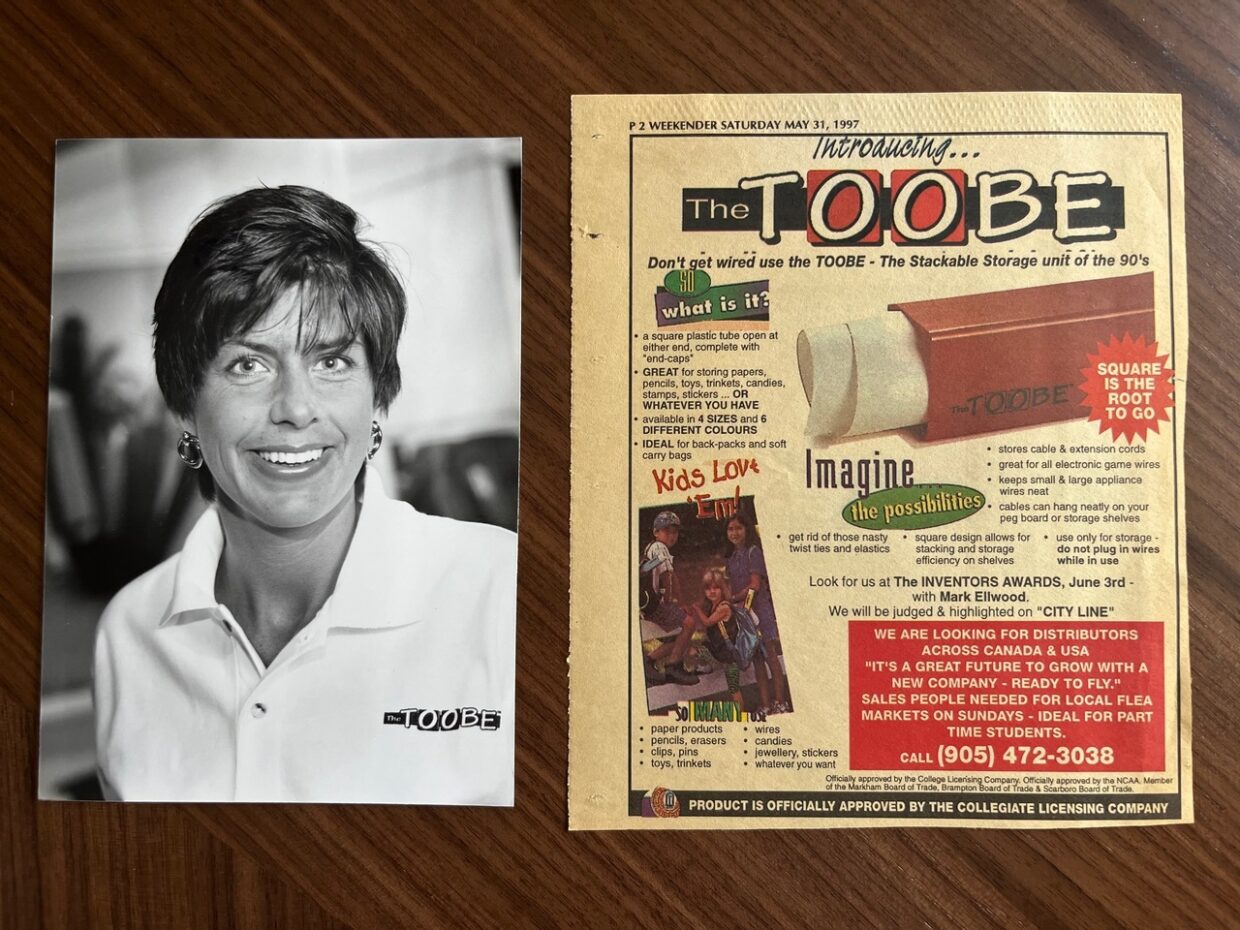

My mom’s team at her booth at the Canadian National Home Show.

My mom’s team at her booth at the Canadian National Home Show.

When I was back in Toronto in July, I had the moment to pore over the photos of her at tradeshows and the Toobes old marketing materials and was taken by surprise. I felt my throat close up as I looked at this woman—my mother, who was around my age now and had three kids and had invented something. Looking at a photo of her beaming her bright white smile at the Canadian National Home Show, I wanted to sob but didn’t. My grief felt as stale and dry as this summer season.

Since she died three years ago, her identity as an alcoholic has helped me dissociate side-step the freight train of grief that daughters feel in the wake of a mother’s passing. I often joke that I’d already used up the well of my tears as a child and teenager, during our fights about rehab, sobriety, and wanting a “normal mom.” But as I stared at the images of her with her “staff,” which consisted of my brother, sister, and me, our dad, two of her friends, and our aunt—all in matching shirts in front of a booth she had designed, I see something I hadn’t seen before: hope. And it’s stunning. My mother was beautiful, even modeled for a time, but when she looked hopeful, she was a knockout.

Some sketches from her booth design + a Michigan Wolverines trace-cut for a design.

Some sketches from her booth design + a Michigan Wolverines trace-cut for a design.

I dug deeper into the boxes, hoping for a VHS taping of her appearance on The Camilla Scott Show—Canada’s version of The Ricki Lake Show. A Google search tells me it aired during season one, episode 74 entitled “Inventions.” I can’t find any video evidence of that particular episode, but I know it happened, since I was there. At age eleven, I sat in the studio audience with my dad and grandmother during the taping in 1997. The three of us cheered on command with the rest of the crowd as we watched my mother present the Toobe in a gorgeous cream suit, chunky gold necklace, and her signature orange hue lipstick.

Sure, my mom had a serious drinking problem—I knew that even then—but I overflowed with pride nevertheless. I saw my mother as capable of magic. She was able to escape the confines of our suburban life through sheer will and imagination. I was already tending a seed in my mind that I, too, could pluck something from my brain and turn it into a real, living thing. And there she was, showing me the way.

There is so much that I have rejected from my mother. But I don’t think enough about the part of my mother, the inventor, that so clearly influenced me.

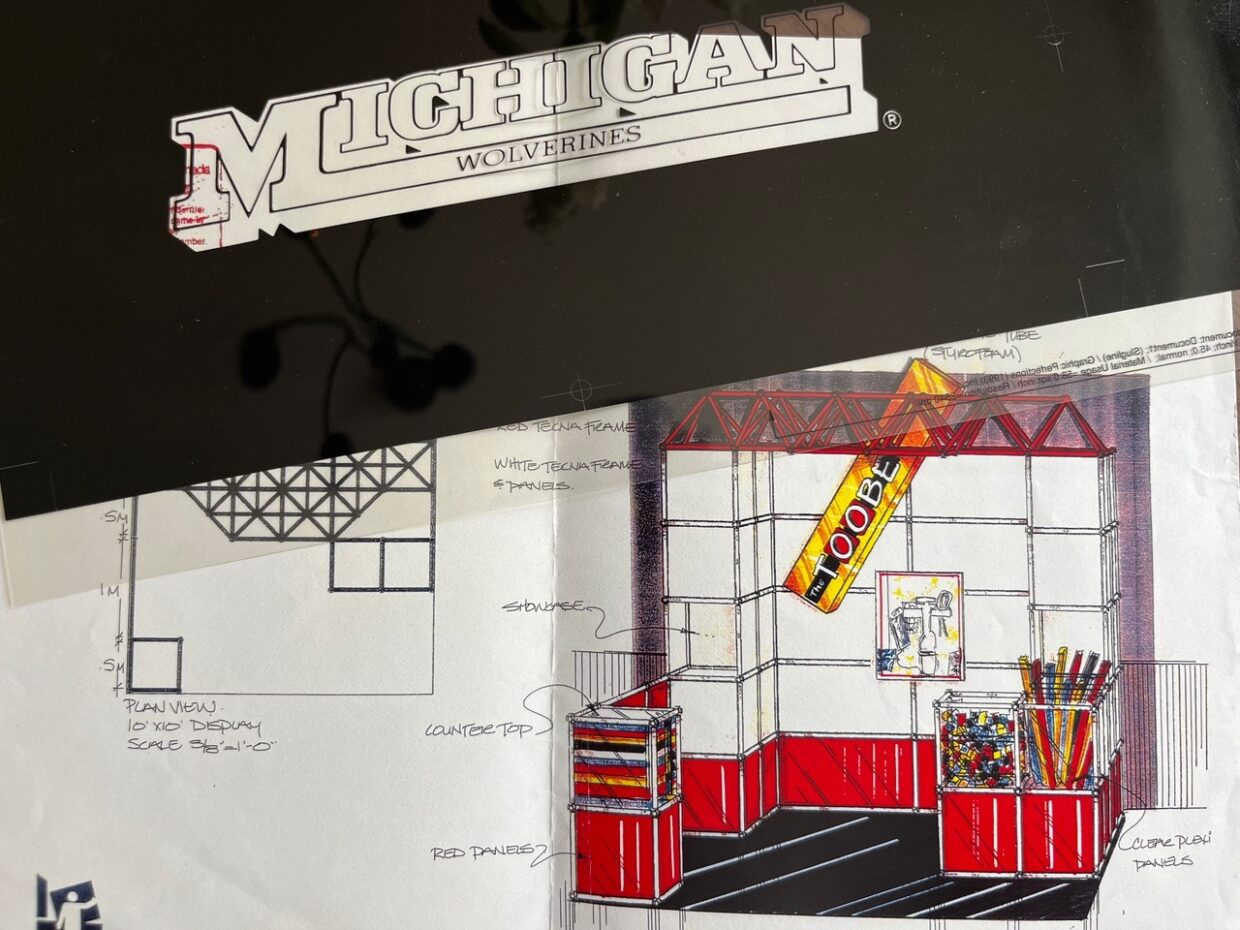

There are many versions of how the story unraveled from that moment. I try to anchor the narrative with what I know for sure. My dad often worked late. We only saw him in the mornings or right before bed. Then, after we went to sleep, he’d spend many nights working on mom’s accounting for the Toobe’s reports, legal patents, and marketing. After some success, they were able to license logos from big American universities and some of their teams. The Michigan Wolverines and the Georgetown Hoyas were two big wins. The orders got bigger, but the customer base didn’t.

Then, they realized the caps wouldn’t stay on the ends of the Toobes. One of my friends would often get reprimanded from our teacher when her pencils exploded all over the floor in the middle of class. (She used that thing until she graduated, even though it never worked, and long after The Toobe was abandoned). Mom’s drinking peaked during that time. There was the stress, the investments, the travel. The overhead.

When mom and dad’s late-night dreaming turned into foul fights, I pressed my ear to the vents. I heard her shout about not having enough time, money, and respect. Dad would question her drinking, which was like squirting lighter fluid on a roaring fire. Yet, I hear that original plea like it was yesterday, like it was mine. As a world-builder, you need unconventional, unwavering support from your partner. Her words now echo in the wake of the same demands I call for during my arguments with my spouse as I seek more time to dedicate to my own writing. And I know I’m not the only mother who feels the frustration when it comes to balancing caregiving and creating.

A huge Lightbox photo on plexiglass of my brother, sister and I modeling the Toobes.

A huge Lightbox photo on plexiglass of my brother, sister and I modeling the Toobes.

My mom moved out a few years after that television appearance. Her drinking meant my dad won custody of us. She tried to console us that she’d be okay, happy that she would have time to herself again. But she never invented or worked again. She lost her driver’s license and rarely left home. About a decade later, it cost the family thousands of dollars to throw away all the unsold overstock that was left in our garage.

When I was in my mid-twenties, I made the impossible decision to cut ties with my mother, too. When she was diagnosed with late-stage cancer in 2022, we hadn’t seen each other in over thirteen years. One of the last things she asked when I finally visited her was if I had become a writer. “It’s hard when you’re a mom,” she said. “You’ll see.” She was so out of it, I wondered if she had forgotten I already had a child. Maybe it didn’t matter.

I picture my mom on tv, all put together in that suit. Then I picture her again, in sweats and barefaced, hunched over tracing paper in the basement at night. I wonder how many times she succeeded in ignoring the siren call of white wine chilling in the fridge. How many times did we ask her to play, or to read to us, right when she was on the cusp of a tagline. To be, or not to be. What was it again that I wanted to be?

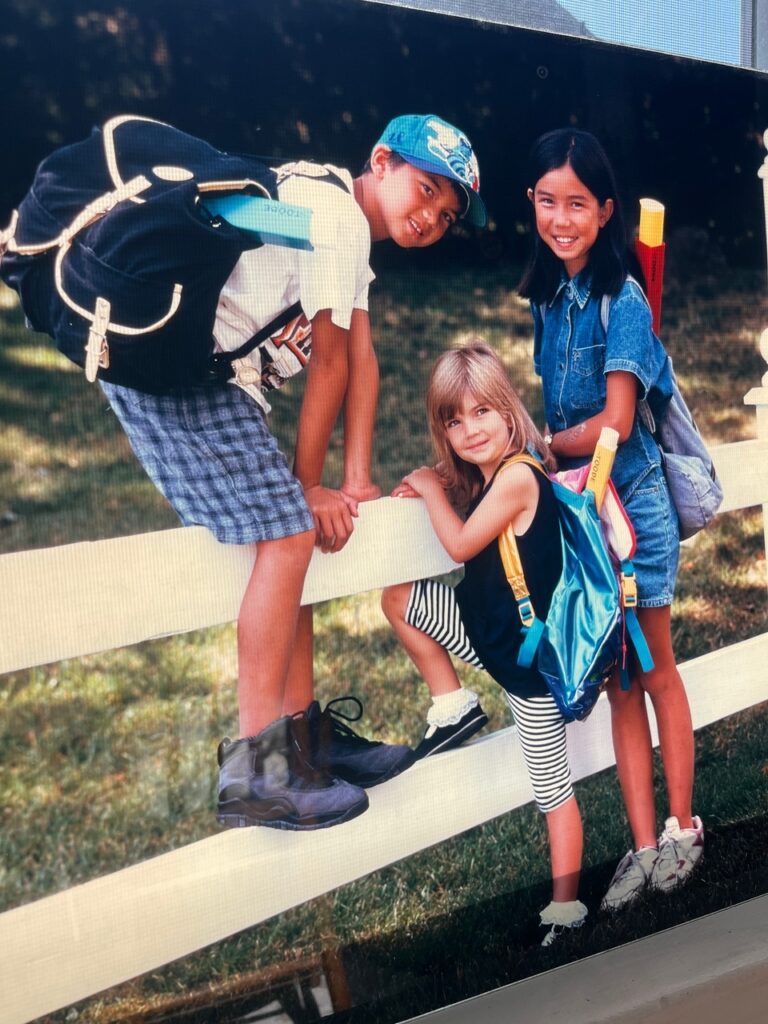

The Toobes I ended up keeping.

The Toobes I ended up keeping.

There is so much that I have rejected from my mother. But I don’t think enough about the part of my mother, the inventor, that so clearly influenced me. Sometimes a failure, not easy to sell. But a sturdy girl no less, with squared edges—difficult to keep a cap on, impossible to throw away.

The June before I visited home, my dad texted my sister and me: “I have 2 boxes of Toobes. Should I keep them or toss them?”

“Toss,” my sister wrote back immediately. My sister had shouldered the heavy burden of caring for our mother in her final years, after which she was left with nearly all of our mother’s remaining belongings that had been left in her home.

“Wait,” I texted back. “Can I have a couple?”

“I’ll give you both a few.” he replied.

My sister wrote back without hesitation, “I don’t want any.”

I knew I didn’t need them either, but I still took them. My sister had taken what she needed from my mother already, but had I? Maybe what I had been left with was the knowledge that there is no writing time, “me” time, mothering time, reading time. The “ideal creating time” is something that doesn’t exist. Sometimes, the essay needs to be written on a piece of scrap paper while pulled over on the side of the road. One day, I might have the spacious office, kids in college, and hours of free time to invent and play. But who I will be in fifteen years is impossible to know.

For now, I’ll opt for sweatpants huddled over my manuscripts, trying my best to ignore the call of a cold beer and the mounting pile of objects from my mother—items that weigh me down and will likely cost money to get rid of. But, looking at the small storage units of the Toobes, I also imagine my grief there too, dissected, spread, and stored into little manageable spaces.

Coco McCracken

Coco McCracken is a Chinese-Canadian author and photographer living in Portland, Maine. She won the 2021 Maine Writer's and Publishers Alliance (MWPA) chapbook competition when The Rabbit was selected for the grand prize by bestselling author Melissa Febos, who called it “pitch-perfect.” Coco is an Ashley Bryan Fellow, an MWPA Lit Fest Fellow, a Hewnoaks artist resident, and recipient of grant from the Maine Arts Commission. Her work has been featured in Maine Magazine, Copy Mag, The Portland Press Herald, New York Times’s Wirecutter, Amjambo Africa, and more. Her writing can be found on her Substack, Coco’s Echo and is presently at work on a memoir.