9 Novels in Which Houses Have a Life of Their Own

From the Creepy to the Comforting, Melanie Hobson on the House as Character

I’ve always felt that the structures we inhabit bear a great responsibility for who we become. For how we behave, and for how the outside world works upon us. In my novel, Summer Cannibals, it becomes apparent that the Blackford family home is itself a character. “. . .it was the house. . . that had colonized them. . .” a character tells us. And certainly, as I was writing, that house often spoke to me—not surprising, because the Blackford home is, with some additions, the house I spent my teenage and young adult years in.

Until we landed at that big house on the cliff, since the day I’d been born, our sprawling family had lived in 14 houses in 12 cities and three different countries. That’s nearly one home a year, as my parents sought new opportunities and my father completed his medical training: fellowships, immigration laws, wanderlust. But this house, the house on the cliff—it felt permanent. My family owned that house for 33 years which, for us, was akin to holding it for generations. I was married there, as were two of my sisters, and even as we left, we always circled back—for summer holidays, for family reunions, as a stop-gap between jobs or living arrangements. . . always, the house was there for us. So, in many ways, writing the Blackford home was a love letter to my childhood home, and a recognition of the power a place can have over you, the way it can continue to reverberate. Although the Blackfords are a very different family than my own family, the house is their refuge too.

Here are nine novels wherein the house is a central character:

Kazuo Ishiguro, The Remains of the Day

In Kazuo Ishiguro’s novel, The Remains of the Day, Ishiguro uses perfectly calibrated language to show the steady dissembling of Mr. Stevens—the butler of Darlington Hall. As Mr. Stevens embarks on a six day tour of the English countryside, Darlington Hall is in the passenger seat, and the farther away Mr. Stevens travels, the more fully realized the Hall becomes until we begin to see that this grand English house has been managing world events in wartime and peace; and its agency will only continue with the American who’s moving in. I think the Blackford home has a similar durability and provides, for its inhabitants, a sanctuary or protected citadel which allows their passions to dominate. Rather than trying to rehabilitate its occupants, the Blackford home seems to convey to this family that everything beyond its boundaries is provisional, and therefore its rules are not to be bothered with. A line from an early draft of my novel describes the view from the house thus: “Beyond it, past the lake, there was the world; an encampment that went for miles.” I still feel this way about the Blackford house, that it is their certainty. The catalyst which allows them to behave as they do.

Magda Szabo, The Door

Emerence—one of the lead characters in Magda Szabo’s novel The Door—lives in a flat which the narrator (her employer) refers to as The Forbidden City. Although Emerence is in and out of the other homes on her street—to clean, to iron, to deliver food to the sick—no one is allowed to even look inside her home. Perpetually shuttered and locked, it is a brooding character in this complicated story of love, and of what is owed to whom and why. When the door is finally opened, the flat reveals itself in shocking ways, and I find this curtain between public and private life endlessly fascinating. It’s a duality we all have, a universal condition, and the tension between the two is one which is rich for fiction. It resonates with me, also, because of the tension a writer feels between their real and imagined worlds.

Sarah Waters, The Little Stranger

In Sarah Waters’ novel The Little Stranger, set in England just after WW2, the house at the center of the novel is a grand manor named Hundreds Hall. “Hundreds is lovely,” declares the sister of its current master. “But it’s a sort of lovely monster! It needs to be fed all the time. . .” The family, which has owned and lived in it for several hundred years, is now reduced to a mother and her two adult children. They live mostly in the parlor as the house deteriorates around them, but as the wallpaper fades and peels, and the roof begins to leak, it seems to gather strength to launch one final sustained assault on the family which has failed to maintain it. “It wants to destroy us, all of us. It’s all very well my standing up to it now,” says the brother, “but how long d’you think I can go on like that? And when it’s finished with me—” This book, in full delightful gothic mode, brings Hundreds Hall to life as a malevolent presence in the lives of this family.

Ian McEwan, The Cement Garden

As someone who gardens, the idea of cementing over an area that can be used to grow things is anathema. In every home I’ve ever lived—even the tiny rentals, early on—I’ve planted gardens. Sometimes for food, but more often flowers of one sort or another to bring explosions of life and color into a landscape that’s too often without it. There’s something eternally hopeful about the way a plant will battle on, despite drought or temperature or infestation. We had a huge fuschia oleander in our backyard in Texas and it bloomed relentlessly, drawing your eye to its flamboyance and away from the empty parking lot across the street, or the ramshackle houses that our neighbors up and down the block were too poor to maintain. I would sit next to that oleander at the table we’d bought from the Catholic Charities, and imagine my way out of that little dirt yard with its fire ant hills.

The slimness of Ian McEwan’s novel, The Cement Garden, belies the magnitude of what it contains. Before he dies, a father accepts a delivery of cement to the family’s house. He plans to use it to cover his garden and his child’s reaction—“. . .mixing concrete and spreading it over a leveled garden was a fascinating violation”—is an indication that this is a home where violations are not unusual. All the other houses on the street have been torn down for a motorway that was never built, and so it stands there in a diminished landscape like the lone survivor in a bombing run. When the parents die—father first, and then mother—the children assume the role of adults and the strangeness of the house pairs with their own behaviors, resulting in a novel that will make you wish you could mix the cement yourself and entomb this house forever.

Sadie Jones, The Uninvited Guests

In The Uninvited Guests, Sadie Jones gives us two houses—one ancient, and the new one which has been attached to it. One inhabited, and one closed up. In one fateful evening, the wall that separates them is broken down; just as the break between the living and the dead is temporarily mended, allowing passage between the two. Both houses are a refuge that exist apart from the larger world, obeying their own sense of time and reality. They are houses where a pony may be found upstairs in a child’s bedroom, and where a bonfire in a great room can ease the dead to their rest. This book has such a subtle rip tide to it that you don’t realize, until you’re too far out, that reality has slipped its moorings. But that newly opened house keeps you afloat, even as it pulls you out. I loved this book, not only for the exquisite writing, but for the promise it held out that even in the most domestic of settings. . . magic resides.

Tessa Hadley, The Past

Tessa Hadley’s novel, The Past, is set in the crumbling country home of the main characters’ grandparents. It is the house where the four siblings spent their childhood summers, and to which they’ve returned to decide its fate now that their grandparents have died. Filled as it is with family memories, it exerts an influence over them which is as strong as the literal building is weak, and this whole idea of a “summer house” carries with it a powerful nostalgia—even for those of us who’ve never had one. It’s the desire for a place where the grind of daily life is suspended, and family time is spent in a sort of gauzy swoon of board games and laughter and endless meals and conversation. But like any holiday, there’s a duration that’s golden and then there’s staying too long. That swoon can quickly become a kind of suffocation. Nostalgia comes from the Greek words for “return home” and “pain,” and certainly there are times when the return comes first, and then the pain follows—as is the case with this novel. And of course memories, when re-examined, are always lacking and what fills them in, or fills them out, is often what you chose to forget in the first place. And it’s hardly ever good. There is something delicious (and devilish) about adult children returning to the scenes of their crimes and perhaps realizing that not everything can be excused by the trite excuse that, “we were just kids.”

Tim Winton, Cloudstreet

Cloudstreet is Tim Winton’s large-hearted epic of two families who, for 20 years, share the “great continent of a house” that this marvelous book is named for. The rollicking Pickles and the straight-laced Lambs, both down on their luck and driven to the city by separate tragedies, form an unlikely community and it is our great fortune that we get to see the “whole restless mob of [them]. . . in the dreamy briny sunshine skylarking and chiacking about. . .”. It’s not too grandiose to say that this house, and this novel, contain Australia. And for someone like myself, whose childhood until 15 was a ramble from house to house, this makes perfect sense to me. I know the way in which homes can be ports in a long voyage toward that eventual, permanent place which you colonize and make your own. The way your extended family and their activities might constitute a nation, and that within the scope of a handful of interconnected lives there might be contained all the progress and setback and hope of a civilization. Tim Winton’s great rooming house, his Australia, is a hulking breathing openness which he floods with light.

David Vann, Dirt

David Vann’s chilling novel, Dirt, takes place on a family property in California’s Central Valley: a house and farm shed surrounded by a walnut orchard. A mother and her 22-year-old son live here in a sort of false old-timey existence—the house with its parlor and the wide-planked floors, the glass pitcher of lemonade, the cast iron table and chairs under a fig tree—and the terrible event which unfolds in the shed is thrown into even greater relief by the steadfastness of this house. It is as if its failure to register any change is in fact a lack of empathy or compassion. A riveting coldness that runs through this book. It’s an emotionally difficult read, but there’s something about the son’s resolve that’s a triumph over the house and the stagnation it represents, even though the final reckoning is a rejection of filial piety. Perhaps this will be enough to uproot the trees. Enough to crush the house, to open the property to the outside world. To escape. Because isn’t it true that a dwelling can be a prison, while also being shelter? And perhaps it takes an act of perversion—or inversion—to break yourself out.

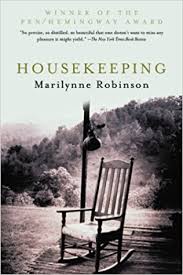

Marilynne Robinson, Housekeeping

The home at the center of Marilynne Robinson’s Housekeeping is a fixed node in a family which tends toward transience. Its presence in the narrative, as well as within this Fingerbone, Idaho family, is one of quiet stability. As steadying as the town’s lake is uncertain, a reminder that home never leaves us—although, there is a sense in which the careful and conscious construction of home highlights how contrived the idea of “home” can be. I’m not unusual, in that my life story is a tale of migration. I have no ancestral lands, my life has been divided between three different countries, there are no heirlooms and very few family stories being passed down between generations—I have cousins I’ve never met. I’ve heard rumors of a “family Bible” and its record of a relative who was a pirate of Penzance infamy, but I’ve never met the holder of that tome and don’t even know his or her name, or what continent they’re on. And this is what I find fascinating about Housekeeping. It gives us a created home and, by doing so, questions its validity.

Melanie Hobson

Melanie Hobson holds a BA Honors summa cum laude in Classical Studies from McMaster University, was a Michener Fellow in the MFA at the University of Miami, and a Kingsbury Fellow in the PhD Program at Florida State University. She was born in New Zealand and immigrated to Canada, with her parents and sisters, as a child. After a few summers working on archaeological excavations in Greece, she moved to the United States and now lives in Florida with her husband and two children. Her first novel, Summer Cannibals, is available from Grove Atlantic.