9 Books You Should Read This December

Anne Carson, Jenny Diski, Daniel Ellsberg, and More

Euripides, Bakkhai, trans. Anne Carson

(New Directions)

In the characteristically unusual translator’s note to her translation of Euripides’ Bakkhai, Anne Carson writes, “The shock of the new / will prepare its own unveiling / in old and brutal ways.” Carson, as a poet and classicist, has long interwoven the ancient with the avant-garde. Her translation of this Greek tragedy, first performed in 405 BC, reawakens the original’s sublimity and gives us the opportunity to be absorbed and shocked anew by the story of Dionysus, who is, in Carson’s playful rendering, “something supernatural – / not exactly god, ghost, spirit, angel, principle or element – / There is no term for it in English. / In Greek they say daimon – / can we just use that?”

–Nathan Goldman, Lit Hub contributor

One of the wildest tragedies of Euripides, The Bacchae tells the tale of a mortal who won’t own up to desiring to live in the body of a woman, and a furious young ambisexual god, Dionysus, trying to cudgel admiration from all comers. Swinging from reason to desire’s arsonist instincts, The Bacchae was once considered too radical to even perform. Which is a shame because it has some of the most beautiful choral passages in all of Greek drama. This version was put on by the poet Anne Carson in London in 2015. Now you can read the text itself and move the bar for insanity in a society out a little further than nasty tweets.

–John Freeman, Lit Hub executive editor

Robert Bausch, In the Fall They Come Back

(Bloomsbury)

This year saw the publication of several excellent novels set in high schools. There was Lindsey Lee Johnson’s The Most Dangerous Place on Earth, which introduces us to an idealistic young teacher in wealthy San Francisco, and Christopher Swann’s Shadow of the Lions, a literary mystery portraying life in a boarding school years after an unsolved murder. Now we’re treated to Robert Bausch’s In the Fall They Come Back, the latest by the talented author of seven novels, including Almighty Me, the fantastical comedy eventually adapted into the film Bruce Almighty. Here Bausch is writing in the realist vein—his finest mode—to tell the story of Ben Jameson, a new teacher who wants to save his most troubled students. This richly drawn portrait of a private school explores the harsh realities of teenage life and the pitfalls of altruism. It’s a deeply affecting read that’s both generous toward and critical of the people who try to help us.

–Amy Brady, Lit Hub contributor

Fiona Mozley, Elmet

(Algonquin)

Things I enjoy in books: nervewracking stories where the specter of sinister events lurk in the background. Things I also enjoy in books: powerful and evocative accounts of growing up and gradually understanding the world around you. Thus, the appeal of Fiona Mozley’s Man Booker-nominated novel Elmet, which tells the story of a family living in isolation and the ominous forces that come to threaten them.

–Tobias Caroll, Lit Hub contributor

Val McDermid, Insidious Intent

(Grove Atlantic)

Val McDermid’s latest in her Tony Hill and Carol Jordan is a perfect example of how to keep a long-running series fresh, relevant, and full of surprises. Policewoman Carol Jordan is battling alcoholism and wracked with guilt over her tangential involvement in a drunk driving accident, while psychologist Tony Hill has moved in with Carol to keep her sober. The two, along with their talented team, investigate a killer who’s targeting single women at weddings, creating a sense of romance, and then brutally murdering them. From painful isolation at a romantic event, to the solitude of guilt, to the unbearable fear of online humiliation, McDermid is skilled at mapping the loneliness of the modern world. The reader need not fear sinking into an unbearable pit of isolation, however—McDermid provides her characters some occasional respite through unlikely friendships and communities.

–Molly Odintz, Lit Hub editor

Alive in Shape and Color, ed. Lawrence Block

(Pegasus Books)

If one of my favorite crime novelists wants to make a habit of releasing an art-inspired anthology every year around the holidays, I’m not going to complain. In fact, I’m going to support that endeavor, full stop, and almost certainly will foist the thing on a few more or less bewildered relatives at the holiday book swap. Last year, with In Sunlight or in Shadow, Block gathered luminaries of the crime and mystery worlds to ruminate on the works of Edward Hopper, with each story in the collection inspired by one of Hopper’s paintings. (Megan Abbott’s “Girlie Show” was a highlight and has stayed with me since reading.) This year, the concept was expanded to include paintings from “the whole panoply of visual art” and a new crowd was brought in. I’m especially looking forward to contributions from Blocke, S.J. Rozan, Lee Child, Sarah Weinman, and Joe Lansdale, among many others.

–Dwyer Murphy, Lit Hub editor

Daniel Ellsberg, The Doomsday Machine

(Bloomsbury)

Here’s a fun activity: think back to how many times America has been on the brink of full-scale nuclear war over the past 60 years, despite being helmed by a succession of relatively sober, if oftentimes nefarious, political operators. Now consider the fact that the current US stockpile of nuclear warheads still numbers north of four thousand at a moment when the current commander-in-chief is busily leaving bags of shit on the doorsteps of as many unstable and nuclear-armed regions of the world as he can find. A new book by Daniel Ellsberg (he of the Pentagon Papers fame), The Doomsday Machine: Confessions of a Nuclear War Planner, seems the ideal accompaniment to these cheery musings. Mixing memoir and history, it’s a chilling look at the realities of America’s nuclear-weapons apparatus from a man who was in the room as Dr. Strangelove-esque hypotheticals about global nuclear winter and death tolls that could exceed 100 Holocausts informed actual geopolitical policy. Happy Holidays.

–Dan Sheehan, Book Marks editor

Jenny Diski, The Vanishing Princess

(Ecco)

New writing from Jenny Diski has always been a cause for celebration, but this book, coming as it does a year and a half after her death from cancer in 2016, feels especially like a gift. Originally published in the UK in 1995, The Vanishing Princess was Diski’s only collection of short fiction, and the stories within circle around some of her lifelong writerly preoccupations: sex and madness and the trauma of her early upbringing. As the title suggests, it also sees her participate in what feels like a rite of passage for all transgressive feminist writers: the reinvented fairytale. Whatever you come looking for in The Vanishing Princess, there is much to discover and be thankful for.

–Jess Bergman, Lit Hub features editor

Why hello, nice to meet you, I have come tardy to the Jenny Diski worship. But better late than never. This hilarious, piercing, brazen, iconic voice passed away of lung cancer last year, and boy are we her public blessed that she saw fit to break us off with one last offering: the U.S release of her collection of short stories. Whether you are a long-time lover of her essays and memoir or if you are like me just, discovering her anew, this collection has something for you. From a re-imagined Rumpelstiltskin to a shut-in Rapunzel-esque twist, you’ll be sure to find yourself satisfyingly tangled up in menacing fairytales turned inside out. Don’t sleep.

–Angel Nafis, Lit Hub editorial fellow

Mary Beard, Women and Power: A Manifesto

(Liveright)

Our most famous living classicist’s most recent work—two essays adapted from lectures delivered in 2014 and 2017—traces our cultural conception of power as inherently gendered from ancient Greece to today. “If we go back to the beginnings of Western history,” she writes, “we find a radical separation—real, cultural and imaginary—between women and power.” The first essay begins just there: at the “first recorded example of a man telling a woman to ‘shut up'” (near the opening of the Odyssey, when Telemachus informs his mother Penelope that “speech will be the business of men”). The way forward Beard suggests is not for women to simply infiltrate spheres that have been male-dominated for millennia; instead, she argues, we have to fundamentally alter the way we perceive power.

–Blair Beusman, Lit Hub associate editor

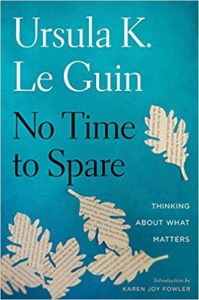

Ursula K. Le Guin, No Time to Spare: Thinking About What Matters

(Houghton Mifflin Harcourt)

This is hardly fair, because I’m always excited for new Le Guin. Obsessives are funny that way! This volume collects some of Le Guin’s best online writing (this is a woman who started to blog in her 80s, which honestly is reason enough to poke around in it), and is such is comprised mostly of brief, pithy musings on everything from feminism to swear words to Great American Novels to breakfast. If you’ve ever wanted to cozy up next to the legendary SF author, this is probably as close as you’re going to get. If you’ve never wanted anything of the kind, first of all, get out, and second of all, the insights and winning prose on display here may just convince you otherwise.

–Emily Temple, Lit Hub senior editor