9 Books by Latin American Women Writers We'd Love to See in English

And a 10th to be Chosen by You

The keen-eyed among you may notice that this list (one of many in a series highlighting—and rectifying—the disparity between the number of literary works by women writers and their male counterparts from all around the globe published in English translation) is a little Chile-heavy. Four out of nine of these women writers hail from a country to which none of us has any especial attachment. This inadvertent discrepancy perhaps tells us something about the inherent folly of pooling women writers on the basis that they are from the same (vast and politically, culturally and linguistically heterogeneous) continent. Note, too, that we’ve purposefully left out Latin America’s biggest country, Brazil, to leave what must be an overabundance of promising Lusophone female writers to feature on their own list.

We have no doubt that what our list lacks in geographical symmetry, it makes up for in talent. But to begin to repair the imbalance, we’ve left number 10 blank. Which Peruvian, Colombian, Uruguayan, Nicaraguan, Dominican, Puerto Rican or other Latin American novel by a female author do you believe is missing? We want to know your thoughts in comments below or on Twitter using the hash tag #LatAmWoLitHub. Please remember: the novel, book of chronicles or short story collection in question must not have been translated into English (it’s fine if the author has); and the female writer must be Spanish-speaking, from a Latin American country.

At the bottom of our list of books we’d like to see in English translation, we’ve also included a selected bibliography of novels by women writers that either have been published or are in the process of being published in English—works we admire and urge you to seek out. Other Latin American authors to keep a close eye on: Magela Baoudoin (Bolivia), Alejandra Costamagna (Chile), Camila Gutiérrez (Chile), Amalia Andrade (Colombia), and Paula Porroni (Argentina) . . . There is never any end to a list like this, so please keep the conversation going with #LatAmWoLitHub.

–Anne Vial (literary scout), Katie Brown (literary translator), Katherine Silver (literary translator), Sophie Hughes (literary translator)

Inclúyenme afuera (Include Me Out) by María Sonia Cristoff (Editorial Mardulce, 2014)

The main character of this slim but densely imagined 156-page novel is a simultaneous interpreter who moves to a small provincial town in Argentina so that she can speak as little as possible for a year. The advantages of her dull job as a guard in the local museum are threatened when she is asked to assist in the re-embalming of the museum’s pride and joy: two horses, of great national and historical significance, are disintegrating and must be saved. But her goal and her slippery grasp on sanity lead her to turn to more anarchistic means to bolster her purpose. Who knew the art of embalming could be so compelling and potentially explosive!

Why translate it?

The novel is bold, subversive, and threaded through with acidic humor. A novel firmly within the more cerebral Argentine literary tradition of Borges and Aira… turned on its head. At a time when we are inundated with chatter of all kinds, it is a homage to silence, and the impossibility of achieving it. What’s not to love about a writer imagining a character who is doing in life what the writer is doing in her art: rethinking the terms on which she lives/writes.

Los jardines de Salomón (The Gardens of Solomon) by Liliana Lara (Sudaquia, 2014)

Obsession is the theme running through Liliana Lara’s first collection of short stories, Los jardines de Salomón, winner of the 2008 José Antonio Ramos Sucre Biennial Literary Prize. From Ernest Hemingway and the French language to spanking or Nina Hagen performing almost naked on Miss Venezuela, the obsessions of children, teenagers, teachers and bored businessmen are brought to life through Lara’s intimate and confessional writing style, creating an intense and utterly engrossing collection.

Why translate it?

For the honesty, humor and emotion evoked in these short stories. For foreign readers, Los jardines de Salomón is also a wonderful geography lesson, portraying parts of Venezuela rarely seen in contemporary literature, like Cumaná, Catia and Maturín. These lesser-known cities chime with the everyday dramas depicted in the stories, providing a refreshing change to the tales of Caracas violence that so often reach international readers.

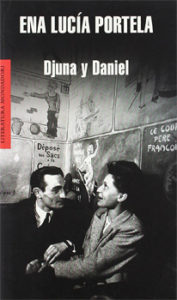

Djuna y Daniel (Djuna and Daniel) by Ena Lucía Portela (Random House Mondadori, España; Ediciones Unión, Cuba, 2008)

A fictionalization of the relationship between Djuna Barnes (modernist author of the cult 1936 novel Nightwood) and Daniel Mahoney in 1920s Paris. Having been sent an underlined copy of Nightwood, Daniel Mahoney discovers that Djuna Barnes used him as inspiration for her character Dr. Matthew O’Connor. Furious, Mahoney goes to confront her in her apartment. It’s not until the final chapter that Djuna opens the door to him and they have the conversation that reveals the reason for his indignation. In a beguiling 1920s Paris—the Paris of Duchamp, Hemingway, Joyce—and with stylistic nods to the latter, Portela portrays a time of sexual freedom and irreducible creativity on the cusp of the Second World War. More than straightforward historical fiction, this novel explores the limits between fiction and reality, between a person and their artistic persona.

Why translate it?

Multi-award-winning Ena Lucía Portela was selected by the 2007 Hay Festival as one of the Bogotá 39 (best Latin American writers under the age of 39). Her fictional worlds brim with universal references that ensure her writing avoids any stereotypical concept of cubanidad. She is nonetheless considered by many of her contemporaries as the best living Cuban authors. Certainly, with her first novel, El pájaro: pincel y tinta china, Portela established herself as one of the brightest voices of her generation. If you need more to tempt you, read Achy Obeja’s translation of Portela’s outstanding One Hundred Bottles (University of Texas Press, 2009).

Qué vergüenza (Humiliation) by Paulina Flores (Chile, Hueders, 2015; Spain, Seix Barral, 2016)

In the title story, “Humiliation,” an out-of-work young father is forced to take his two young daughters with him to interviews and watches as the family of which he is unwittingly at the helm falls apart at the seams. In “Teresa,” a women’s casual flirting outside the library leads to a sinister conclusion (and Flores’ third-person narrator keeps us at a teasing distance from her strange heroine’s psyche so that we are left to chew over a multitude of possible meanings). “Talcahuano” is a sort of Chilean Stand By Me. In a poverty-stricken fishing town, four boys, whose fathers have all lost their jobs due to the downturn in the fishing trade, try to allay their boredom spending most of their lazy summer days hanging out on the porch eating watermelon and translating The Smiths lyrics into Spanish with stolen dictionaries. Until one of them has a devastating idea.

Why translate it?

In the last year, some major publishers on both sides of the pond have snapped up a series of short story collections by young Latin American women writers: search out, for example, Mariana Enríquez (Hogarth US, Portobello Books UK) and Samanta Schweblin (Riverhead US). Paulina Flores, with her ability to shine a light on the dark liminal phase between childhood and adulthood, seems destined to join them. This is a notably assured voice and accomplished storytelling with universal appeal.

Contra los hijos (Against Children) by Lina Meruane (Tumbona, 2015)

Lina Meruane is a prominent female voice in Chilean contemporary narrative. As a novelist/essayist/editor & cultural journalist, her autobiographical novel Seeing Red was recently published by Deep Vellum and sold internationally to Germany, France, Italy, Holland and Brazil. Her essays are passionate and inflammatory. Here she writes a feminist & controversial essay against having children: an angry, powerful and thought-provoking essay that should stir things up and deserves to be read and talked about. Why are women expected to give up their newfound freedom of emancipation in the process of child raising (where men are praised when they “help a little”)? Why do we let social programming and rules dictate our plans, lives and families? Should we allow our children to turn into little tyrants with a busy social agenda? A rant against mothers of the breast-feeding-league and the idiocy of recyclable diapers.

Why translate it?

Because it’s an important voice in the current and yet still taboo debate on #regrettingmotherhood (Orna Donath’s sociological study which raised more than eyebrows, internationally). A call to readers to question the “procreation machine”, to chose motherhood only for the right reasons, and free themselves from this social programming of parenthood, “slavery-in-disguise.” Watch out, this little sassy book could be sold over the pharmacy counter as an efficient contraceptive . . .

Muerte en el Guaire (Death on the Guaire) by Raquel Rivas Rojas (Ediciones B, 2016)

Told as a series of letters from journalist-turned-chef Serenella to her friend Olga in London, Muerte en el Guaire follows attempts by their reporter friend Patty to solve the mystery of the bodies being fished from the river that cuts through Caracas. Published in Ediciones B’s Vertigo series of crime fiction, Muerte en el Guaire—whose title pays homage to the classic of the genre, Agatha Christie’s Death on the Nile—effortlessly brings to life the realities of contemporary Venezuela: partisan conflicts, corruption, intimidation and the limbo of survival.

Why translate it?

Like all great crime fiction, this novel is immensely readable. The short chapters, oral style and suspense make it the kind of book you read in one sitting. And yet, it is a book packed with detail about life in chavista Venezuela, in which the brutal realities are far more disturbing than any crime fiction invention.

Chicas muertas (Dead Girls) by Selva Almada (Literatura Random House, 2014)

Almada is one of the best-known female contemporary writers from Argentina and is published in Germany, Holland, France, Sweden, Italy. This is the odd-one-out: a gripping true crime novel on femicide and violence against women in the Argentine provinces. Three girls from Entre Rios (North-Eastern Argentine province)—are murdered in the 1980s—during Argentina’s return to democracy. The murders never made it into headlines or Buenos Aires TV News, but their cases were covered in local radio, press and kept alive as part of a local landscape of memory, imagination and myth. No culprits were ever found. Almada sets out to expose the truth behind the phenomenon of femicide: a sordid mix of latent misogyny and violence, class differences, a failing judicial system and broad social acceptance. And while the crimes may go unpunished, Almada raises from oblivion these absent women whose lives were brutally cut short.

Why translate it?

A potent mix of In Cold Blood and The Virgin Suicides with filmic qualities. Harsh, (hyper-)realistic murder scenes that haunt us and give us goosebumps. A narrative reading like a countdown to the inevitable disaster. The writing is never cold or distanced, always getting under the women’s skins, giving them a voice by imagining their thoughts, fears and final moments. There is languid poetry in the description of provincial landscapes, domestic life, adolescent ennui. A fusion of storytelling, true crime and journalism (the book was commissioned and is based on interviews), but beyond anything: this is literature.

La resta (The Remainder) by Alia Trabucco Zerán (Chile, Tajamar, 2015; Spain, Demipage, 2015)

A road trip in a hearse. A journey through the Andes as ash rains down on Santiago. A corpse being held at an Argentinian airport and three young friends hell-bent on retrieving it. La resta presents a new way of writing about Chile’s dictatorial past. And the past narrated here is no longer that of the regime’s main protagonists, but rather of their children, who suffer wounds both inherited and of their own. In her epilogue to La resta, Lina Meruane (author of Seeing Red, published by Deep Vellum, translated by Megan McDowell) says: “Here’s a key question that La resta wrestles with: How do we distinguish between a borrowed or imposed memory and our own?”

Why translate it?

Trabucco and her characters are fixated with the power and weight of words. Trabucco (who was chosen by Babelia, the literary supplement of Spain’s newspaper El País, as one of ‘Ten Debuts to Look Out For in 2015’) takes advantage of the novel form to recount a traumatic national past in an excitingly oblique way. Her idiosyncratic language and imaginative technique are at times virtuosic, and these idiosyncrasies are not arbitrary, but symptoms of her characters’ struggle to find their voice.

La dimension desconocida (Twilight Zone) by Nona Fernandez (Random House Chile, 2016)

Nona Fernandez may be one of the best-kept secrets of Latin American literature, with previous novels published by small indie publishers in France, Italy and Germany. Roberto Bolaño was a champion. This could be her break-out book: the story of Andres Valenzuela (“El Parpudo”), an undercover Chilean secret agent & torturer, who repented and confessed to years of horrific crimes against human rights during the Pinochet regime. His confession to a female journalist of the opposition newspaper was recorded and smuggled out of the country (all under great risk of lives). His terrifying testimony—of public arrests, disappearances, brutal torture & executions, mass graves—opens doors to a hitherto unknown universe the author refers to as “The Twilight Zone” (a favorite childhood TV show and key reference in the text). Imagination takes us to those places which memory and archives were unable to reach. “The man who tortured” today lives under-cover in French exile- can a monster be forgiven?

Why translate?

Because it’s a great example of a trend in Spanish language literature these days coming: the fusion of fiction with non-fiction elements of memoir/chronicle/journalism. No need to “label” it: this is simply fantastic storytelling! It’s a riveting political/espionage thriller, and yet a deep reflection on evil, human nature, and forgiveness. A brave, raw & very humane story of torture, terror and redemption—set against a backdrop of (childhood) memory and imagination. For Chile, it’s an important book and likely to be voted “Book of the year”.

Finally: You tell us! #LatAmWoLitHub

*

Some other Contemporary Female Writers from Latin America published or forthcoming in English:

THE THINGS WE LOST IN THE FIRE, Mariana Enríquez, tr. Megan McDowell (Hogarth, US, Portobello Books, UK)

THE CHILDREN, Carolina Sanin, tr. Nick Caistor (MacLehose Press)

AFTER THE WINTER, Guadalupe Nettel, tr. Rosalind Harvey (MacLehose Press)

THE GRINGO CHAMPION, Aura Xilonen, tr. Andrea Rosenberg (Europa)

BLOOD OF THE DAWN, Claudia Salazar Jiménez, tr. Elizabeth Bryer (Deep Vellum)

UMAMI, Laia Jufresa, tr. Sophie Hughes (Oneworld Publications)

EMPTY SET, Verónica Gerber Bicecci, tr. Christina MacSweeney (Coffee House Press)

FEVER DREAM, Samanta Schweblin, tr. Megan McDowell (Riverhead, US; Oneworld, UK)

A SIMPLE STORY: THE LAST MALAMBO, Leila Guerriero, tr. Frances Riddle (New Directions, US; Pushkin Press, trans. Thomas Bunstead, UK)

SEEING RED, Lina Meruane, tr. Megan McDowell (Deep Vellum)

THE BOOK OF EMMA REYES: A MEMOIR, Emma Reyes, tr. Daniel Alarcón (Penguin Classics)

OUR DEAD WORLD, Liliana Collanzi, tr. Frances Riddle (Dalkey Archive)

ONE HUNDRED BOTTLES, Ena Lucía Portela, tr. Achy Obejas (University of Texas Press)

SAVAGE THEORIES, Pola Oloixarac, tr. Roy Kesey (Soho Press)