88 Writers on the Books They Loved in 2022

The Year in Reading From Contributors to Freeman’s

Jon Fosse, Septology

This year, I happened on a book so transcendent that not only is it my best book of the year 2022, it ties 2666 by Roberto Bolaño as my favorite book from the 21st century. I didn’t know what to expect when I bought Septology by Jon Fosse, translated with astonishing grace by Damion Searls; what I read was nothing less than a desperate prayer made radiant by sudden spikes of ecstatic beauty. Septology is almost impossible to describe; it is, officially, seven books, though it is written in one extremely long stream-of-consciousness sentence; the main character is resolutely himself but also fragmented into other selves, as well. It is ambitious. It is sui generis. It’s a book that suddenly expanded my understanding of what fiction can do.

–Lauren Groff, author of Matrix

Ian McEwan, Lessons

Lion Feuchtwanger, The Oppermanns

Georgi Gospodinov, Time Shelter

Perhaps because time in the pandemic was like a fun mirror, alternately stretching and shrinking, it has much been on my readerly mind this year—with Lessons, Ian McEwan’s sprawling and vivid novel of the last seventy years, as well as the re-issue of Lion Feuchtwanger’s extraordinary 1933 novel The Oppermanns, with an introduction by Joshua Cohen. If you’ve wondered what it was like to be in Berlin in the early 1930s, this novel, about a prosperous Jewish family, will take you there: it feels as urgent today as 90 years ago.

This year’s most delightful (yet deeply sobering) meditation on time is Time Shelter, by the brilliant Bulgarian novelist Georgi Gospodinov: the narrator and his elusive doppelgänger/projection Gaustine create across Europe a series of Alzheimer’s clinics in which patients are surrounded by their meticulously recreated pasts. But what will happen when this intense nostalgia seeps out of the clinics and into society, and people turn away from the uncertain future in thrall, instead, to a secondhand future of the past?

–Claire Messud, author of The Last Life

Kamila Shamsie, Home Fire

I was truly impressed by Kamila Shamsie’s Home Fire, which I read for the first time this year. Such a powerful and compelling exploration of Muslim life and identity in the west. So refreshing to read a novel that takes on current political issues without reducing issues or characters to clichés. The novel does the opposite: it deepens, expands, moves, with all the power of the original Greek tragedy, Antigone, that inspired it.

–Fatin Abbas, author of Ghost Season: A Novel, forthcoming in 2023 from W.W. Norton

Julie Phillips, The Baby on the Fire Escape

The arresting title of Julie Phillips’ The Baby on the Fire Escape derives from her in-laws’ claim of painter Alice Neel that she had once left her baby on the fire escape of her New York apartment while trying to finish a painting. No Pollyanna pep talks here for aspiring artists and writers who might also want to be mothers, just a fascinating battery of inconvenient but invigorating truths about creativity and motherhood. Frank, thoughtfully nuanced accounts of female artists and writers draw on the lives of Audre Lorde, Louise Bourgeois, Doris Lessing, Faith Ringgold and Angela Carter among a host of starry others.

–Helen Simpson, author of Cockfosters: Stories

Jean Chen Ho, Fiona and Jane

Whenever I start to get tired and dusty, I turn to short stories about being young. This year the collection I loved most in those moments was Fiona and Jane by Jean Chen Ho. Each story feels like a confession, about something excruciating and exciting that happened to your best friend. I felt nostalgic and mortified from one paragraph to the next. It reminds me of walking home, shivering after drinks with friends, so relieved to be able to go home, but so happy to have gone somewhere.

–Xuan Juliana Wang, author of Home Remedies: Stories

Ellyn Gaydos, Pig Years

In the swirling milieu of fantastic lies and chronic, casual violence that is currently the Republican Party, we crave dirt, honesty, reality: things we can touch, taste, scent, see, smell. In the spirit of John Berger and Melanie Viets, Ellyn Gaydos’ Pig Years is a tale of community, work ethic, socioeconomic inequity, and the stunning beauty and brevity of life.

–Rick Bass, author of For a Little While: New & Selected Stories

Takako Arai, Factory Girls

Set in a silk weaving factory in rural Japan, inspired by the one where Takako Arai spent much of her childhood, Factory Girls attends to the closely-knit lives of women workers. It’s a world of dreams and machines, danger and desire, folklore and fact, capitalism and climate change, nurturing and violence. This is Arai’s third book of poetry but the first that’s been translated into English. Six translators collaborated to bring this book to anglophone readers.

–Tess Gunty, author of The Rabbit Hutch

Lalla Romano, A Silence Shared

I completely disappeared into Free Love, Tessa Hadley’s new novel about a woman’s political and social transformation, and an English world that no longer quite exists. It’s compelling in its narrative, great-hearted in its generosity, and clear-sightedly unsentimental—ultimately, it shows that love, even if freeing, is never free, that someone will always have to go on paying the price. We had a very hot July over here, and I spent it in the company of Lalla Romano’s A Silence Shared, an Italian classic translated into English for the first time. Reading this beguiling book was not unlike watching light and shadow complicate the surface of a still, deep pool of summer water. Hats off to Brian Robert Moore for the stunning translation.

–Sunjeev Sahota, author of China Room

Manuel Muñoz, The Consequences

Roxanne Dunbar-Oritz, Not a Nation of Immigrants

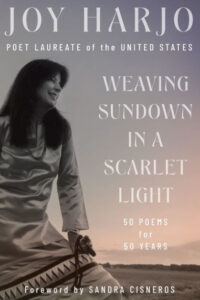

Joy Harjo, Weaving Sundown in a Scarlet Light

I truly adore Manuel Muñoz’s The Consequences; this book makes me envious because the writing is gorgeous, but so is the heart that collected these stories. Great spirit work done here.

My other favorite is Not a Nation of Immigrants, by Roxanne Dunbar-Oritz, which has me looking at ways I can decolonize the colonial town I live in.

Yet another is Joy Harjo’s newest poetry book Weaving Sundown in a Scarlet Light, because it’s a history of her life as a poet visionary through fifty years of her poems and as of this year I have personally admired Joy forty-eight out of those fifty.

–Sandra Cisneros, author of Woman Without Shame

Jessica Au, Cold Enough for Snow

Cold Enough for Snow by Jessica Au is one of the most sublime novels I’ve ever read. From the first sentence, you see the author’s insistence on subtlety pay off. Its themes are familiar, but the way Jessica handles those themes made me rethink assumptions I had about the rules of fiction. A delicate and beautifully written novel, I’ll be going back to it even after the year ends, time and time again.

–Camonghne Felix, author Dyscalculia: A Love Story of Epic Miscalculation