One of my favorite things to do in public is eavesdrop on what other people are reading. If someone is on a subway or standing at a cafe reading a book, I will do almost anything to see the cover. Drop invisible coins, tie invisible shoe-laces. Pet an invisible dog at my feet.

Somehow, it’s not enough to read. Reading alongside others, even if it’s not the same book, is a comfort.

It is in this spirit that I offer this end of year reading list for 2022, featuring the recommendations of nearly a hundred contributors to Freeman’s over the years.

I asked everyone I still had an address for what their favorite read of the year was—any book, from any language, published in any year originally. Here are their answers: from Charles Darwin to Alice Oswald’s poem “Dart.” From books about Keats to follow-up collections by Solmaz Sharif.

I hope you feel the same sense of pleasure, wandering among the passionate stacks with these poets, essayists, biographers, novelists, and reporters. How wonderful to see the many different ways love of a book is expressed. How reassuring that in a world of pattern recognition there are so few patterns here. So few hits and re-hits. But rather a great heaving library of books waiting for you to crack them open, on this holiday, or when you have time next.

–John Freeman, editor, Freeman’s

*

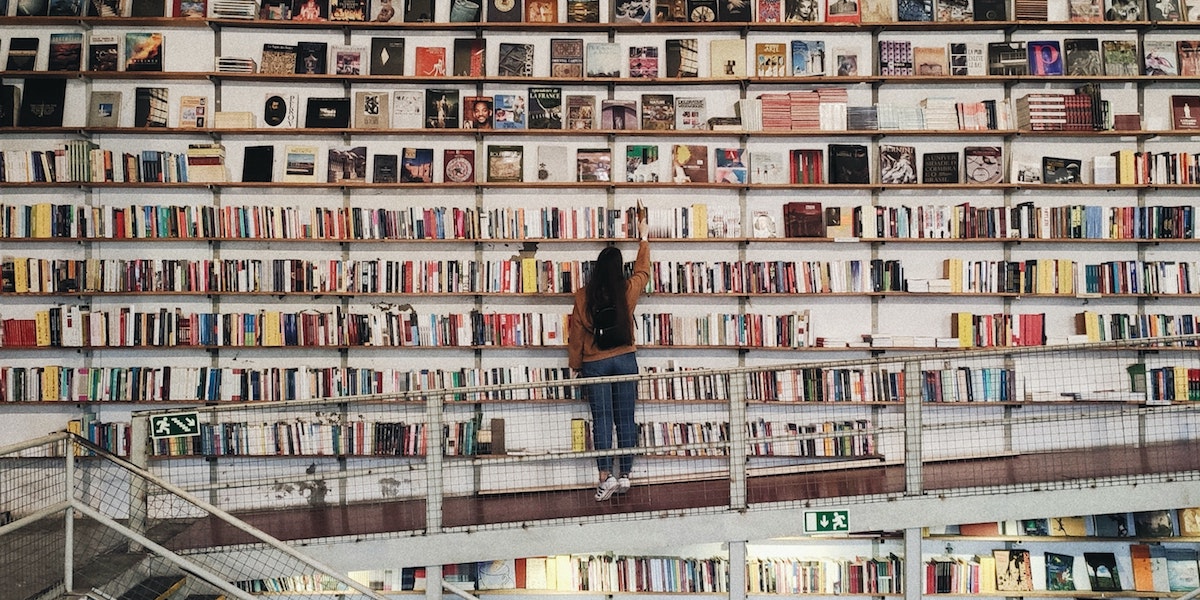

Claire Vaye Watkins, I Love You But I’ve Chosen Darkness

I read Claire Vaye Watkins’ I Love You But I’ve Chosen Darkness and really dug it. It has a blood and guts quality, visceral, that I found refreshing. Poetic jags of full tone and big mood. The letters in it from the author/narrator’s deceased mother (written when she was a teenager) took me a bit to get into, but later I decided they were essential, and that the author and the gone mother were collaborating on various uncrackable mysteries to do with women, chance, and Nevada, and making, together, new possibilities for the novel.

–Rachel Kushner, author of The Hard Crowd: Essays

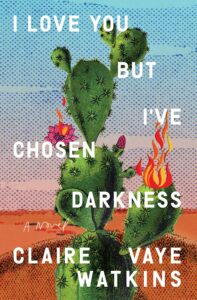

Cormac McCarthy, The Passenger

My fave book this year is The Passenger by Cormac McCarthy. A friend gave it to me as a gift and I read it slowly cause it’s been so long since his previous book. I really don’t know if it’s his best, a masterpiece, whathaveyou. Sometimes you love a writer that yes, is great—and he is—not because of just the greatness but something stranger bordering an invisible kinship. McCarthy writes what I love to read in a style that just floors me and yes it can be solemn but gosh, he starts with the image of a young woman hanging from a rope, dead, suicide, and I don’t want smart sentences and levity, I need this voice that says yes life is full of cruelty but here’s beauty.

–Mariana Enriquez, author of Our Share of Night, translated by Megan McDowell, published in the UK from Granta, forthcoming in the US from Hogarth in 2023

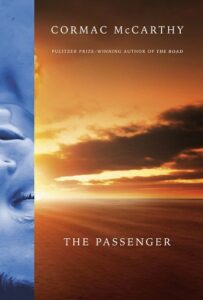

Alice Oswald, Dart

I read Alice Oswald’s poem “Dart” out loud with a documentarian/documentarist friend a few weeks ago. It’s not only one of the most beautiful odes to a river—or is it also a lament?—but also possibly the most fascinating approach to the problem of narrating non-human entities. Oswald does not try to impersonate the river or create some kind of human-non-human persona. Instead, she gathers the language of people who live on and interact with the river, and with the fragments of that language she draws a potent and haunting sound-map of its course, from source to sea. The poem was written exactly 20 years ago, this year. I recommend reading it out loud before the end of 2022!

–Valeria Luiselli, author of Lost Children Archive

Maya Deren, Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti

For many years now, I’ve had this growing suspicion that I know absolutely nothing. Or, to put it another way, I’m beginning to realize, in a profoundly different way, that there is an abyss of difference between accumulating information and knowing. The longer I live, the more I feel well-informed, but remarkably ignorant.

Lately, I have felt this most keenly in terms of literature. Jean Rhys, Katherine Mansfield, Camara Laye, Naguib Mafouz, Eduardo Galleano, Simone Schwartz-Bart, Robert Hayden, Bapsi Sidwha—did I ever really understand any of it? When I read Morrison’s Tar Baby, in awe, as a teenager, how could I have seen all that she was doing with that resplendent crossroad of language, the history of the novel, black interiority, and transatlantic desire, when I myself then—and still now—knew so little? To this end, I’ve been starting all over again—going back and re-readings books I thought I understood, 35 or even 40 years ago, even as I may have completed them 3 or 4 times. Now I understand, it’s utterly probable that I never really read them at all.

This year, one of those books is experimental filmmaker Maya Deren’s Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti.

Honestly, I don’t know whether I will ever understand it. I only know the writing and rigor are stunning. And it reminds me of a time when the attention to language, to the sentence, was normative and serious, not a rare literary skill. Word by word, sentence by sentence—less she allow her reader’s mind to go astray or be under-informed—Deren’s early and now canonical ethnography regarding the Haitian pantheon, cosmology, and theological rituals, is still—almost 75 years later—a deep existential excavation regarding the intimacy shared between gods and devotees. I’m still lost in her genius—her aesthetic and intellectual posture—and grateful to be so.

–Robin Coste Lewis, author of To The Realization of Perfect Helplessness

Percival Everett, Telephone

Telephone by Percival Everett turned me onto a writer that I know is going to rock my world. Effervescent, anarchic and seemingly effortless you cannot predict where Telephone will take you. Percival’s easy humor masks the high risk storytelling and emotional depth of his writing. I look forward to whizzing through the rest of his oeuvre, next up is The Trees.

–Nadifa Mohamed, author of The Fortune Men

Hammour Ziada, The Drowning

A couple of years ago, Sudan had its first Oscar nomination with You Will Die at Twenty based on a short story by Hammour Ziada. The film, beautifully shot in North Sudan with stunning footage of the Nile, tells the story of a baby boy who is prophesied, by a local mystic, to die at the age of twenty and how this death sentence looms over his youth.The film ends without us knowing whether the prophecy has been fulfilled because that was never the point of the story. Hammour Ziada’s latest novel, The Drowning, does something similar.

It opens dramatically with the appearance of the drowned body of a woman at a village near the shores of the Nile. Who is she? Why was she killed? Neither of these questions are ever answered and instead we are plunged into the life of the villagers, their conflicts, histories, and relationships. This is a gripping, visceral novel, written with extraordinary energy. When I finished reading it, I felt as if a storm had ended and I was left strangely with glimpse of the drowned woman and an understanding of why she died, like a scene illuminated in a flash of lightening.

–Leila Aboulela, author of River Spirit, forthcoming in ’23 from Grove Press.

Immanuel Kant, Dreams of a Spirit-Seer

Of the many strong feelings we experience throughout our lives, the desire to see a loved one who has died must be among the strongest. I wanted to know what Kant thought about that possibility, so I read Dreams of a Spirit-Seer. Critiquing Swedenborg’s ideas, Kant thoroughly rejects any notion of the spirit world, and yet in his writing, there are many moments that I found profoundly affecting: moments characterized by what seems like hopelessness, moments in which Kant’s thoroughness reveals his own deep desires.

–Mieko Kawakami, author of All the Lovers in the Night, translated by Sam Bett and David Boyd

Tayi Tibble, Poūkahangatus

This summer while camping on the Oregon Coast I read Tayi Tibble’s Poūkahangatus in one sitting. It broke me open. In it I felt the pull of the ocean. I felt at home in the pages as a Native woman. These poems cut to the bone and demand that you not shy away from the blood, but rather look closely into the generations of story you’ll find there. There is a fierce femininity in these poems, as she examines lineage, history, and the importance of representation. This book is beautiful and unapologetically indigenous, and by far my favorite book of 2022.

–Sasha taqwšəblu LaPointe, author of Rose Quartz, forthcoming from Milkweed in 2023

Hilary Mantel, A Change of Climate

Despite all things imperfect, 2022 has been a good reading year for me, both with other readers and by myself. I began the year by hosting a group reading of Moby-Dick with A Public Space, which took 30 days, and I’m ending the year with a group reading of Villette in 31 days. The group readings under #APStogether have continued to be an anchor for many readers around the world.

My most favorite discovery this year is an older title by Hilary Mantel, A Change of Climate, which feels to me is unfairly overshadowed by her later work, especially the Wolf Hall trilogy. At the center of the novel are an English couple, whose missionary past in Botswana and present life back in England compress decades of domestic and international dramas. The novel tackles many shades of evilness and goodness, none of which fit neatly into any ideology, all of which challenge ready-made and widely accepted narratives. It’s not a comforting or enchanting novel; rather, written out of a dire kind of clear-eyedness, the novel doesn’t leave any space for wishful thinking and makes for an unforgettable reading experience.

–Yiyun Li, the author of The Book of Goose

Kang Hwagil, A Good Person

Ever since I read A Good Person, by Kang Hwagil (Japanese edition translated from Korean) , I’ve been thinking about the air that I’ve inhaled so many times. There were often terrifying demons lurking in it, transparent and terrifying monsters generated by myself or by other people. I was astonished to find them present in the book in the form of language. I stood rooted to the spot like a child, turning the pages. It was a vivid reading experience, as if I had clearly witnessed the darkness of the mind through the light of language.

–Sayaka Murata, author of Life Ceremony: Stories, translated by Ginny Tapley Takemori