9 New Books To Read in June

Recommended Reading by Lit Hub Staff and Contributors

Sanaë Lemoine, The Margot Affair

(Hogarth Press)

The Margot Affair is that perfect mix of literary and entertaining, which was exactly what I needed this late spring: it’s the novel that has taken me out of my mushy-brain, can’t-read-fiction situation. I loved the voice of Margot, the secret daughter of a French politician – her relationship with her actress mother alone had me hooked, but Lemoine’s elegant, deft prose has layers, and this story contains a whole body-of-the-iceberg of emotional turmoil in its wonderfully Parisian (class issues included) characters. This is one of those books that you didn’t know you needed until you read the first few pages and you go: oh, I’m home.

–Marta Baussells, European editor at large

Tara Isabella Burton, Strange Rites

(PublicAffairs)

There are few writers working today who are better at chronicling the overlap of culture and religion than Tara Isabella Burton. Her new book Strange Rites brings a panoply of belief systems and devotions together into one place, showcasing the numerous ways in which people have utilized faith and belief to make sense of the contemporary world.

–Tobias Carroll, Lit Hub contributor

Emily Temple, The Lightness

(William Morrow)

It’s no secret that Emily Temple herself is a favorite of all of ours at Lit Hub, but even if I didn’t know her and know how exact, wry, and brutally intelligent she is, I would be able to tell from this book. The Lightness is everything that I want right now: a story far from my reality, and yet resonant in its depictions of femaleness and friendship, the kind of friendships young women have that are a marriage of sorts. That is: deeply felt, entwined with danger, fear, and love, and when they end, a kind of death. This is especially true for the protagonist, Olivia, who is sent to a summer program for troubled teens and meets the girls that will fundamentally change her life. The Lightness is a perfect summer book, by which I mean addictive, and satisfying, and yet I do not mean light: it is not that. It is heavy with darkness and edges, but in the way that life is, in the way life can be: as well as flecked with humor, and joy, all of it jostling for space and fitting together to make up the whole, fiercely alive, thing.

–Julia Hass, Lit Hub editorial fellow

Masatsugu Ono trans. by Angus Turvill, Echo on the Bay

(Two Lines Press)

This short gem of a novel is part cautionary tale and part fable. A pig and yellowfin tuna serve as metaphors for repressive regimes of the governmental and familial kind. While the ocean serves as an entity that hides sins, coughs them up, and is conduit for successful and unsuccessful trips of relocation. What makes this book special is how a specific Japanese community is portrayed. We hear from a greek chorus of ethnographers, who make sure we are paying attention to what we are learning about the culture of place and the roles that people play in receiving and passing on its intimate history. An enlightening read.

–Lucy Kogler, Lit Hub columnist

Audur Ava Ólafsdóttir trans. by Brian Fitzgibbon, Miss Iceland

(Grove Press, Black Cat)

I love books about the literary flight from the provinces to the city. It’s a tired myth, though, so I was happy to see Audur Ava Ólafsdóttir gives it a thorough renovation in her latest novel, Miss Iceland, smoothly translated by Brian Fitzgibbon. Set in Reykjavik in the 1960s, the book follows its heroine Hekka from the hinterlands into the capital city. Then as now, there’s still a stench of whale blubber by the water, but at Cafe Mokka, a literary set of male poets gathers and ponder imponderables in a cloud of cafe smoke. “What would happen if I strolled into the cloud of smoke with Thoregurdur in my arms and ordered a cup of coffee?” Hekka’s friend asks, while juggling her newborn. Hekka winds up sharing a flat with an equally alienated man, who finds no space in the hyper masculine world of fishing trawlers. Rather than seek acceptance from a world almost deigned to keep them out, slowly Ólafsdóttir tilts her characters toward one another and they find in each other far more than adventure, motherhood, and literary questing ever promised them. This warm book is one of the best hymns to friendship I have read in some time.

–John Freeman, Lit Hub executive editor

Brian Castleberry, Nine Shiny Objects

(Custom House)

When nine UFOs fly over the Washington mountains in 1947, they inspire loners, weirdos, and hard-up desperadoes across the country to imagine a better, more just world. Over the course of several months, the inspired find each other and start their own devout community. To outsiders, they’re a strange new cult. But the believers are convinced that their vision is truth: that the future will be free of racial rifts and other national divides. Nine Shiny Objects is Brian Castleberry’s debut, but it reads like the work of a seasoned writer at the top of his game. Jumping from character to character, and decade to decade, the author weaves an extraordinary saga that captures both the brokenness and optimism of America.

–Amy Brady, Lit Hub contributor

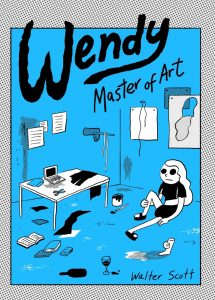

Walter Scott, Wendy, Master of Art

(Drawn & Quarterly)

I felt shaken by Wendy, Master of Art. Walter Scott renders a set of ambitious, naïve, and more than anything messy young people who get smashed together in the same Master of Fine Arts program at the University of Hell in small-town Ontario. These compact and fast-moving comics are funny, poignant, and scary. Scott makes you laugh and then rips your heart out.

–Nate McNamara, Lit Hub contributor

Megha Majumdar, A Burning

(Knopf)

In just 289 pages, Megha Majumdar gives you a whole world. It is a world of corruption and injustice, but it is populated by people who have sacrificed enormously and hope earnestly. Her stunning debut novel begins with a terrorist attack on a train in India. Because of a careless Facebook comment, an innocent young woman is charged with the crime. From prison, Jivan tells us her story. And not just the story of the day on the train, but her whole story. We hear about the injustices her family faced growing up in poverty, the pride her father took in her literacy (my heart!), her aspirations of becoming a teacher. Jivan is the connective tissue of this story, but what makes this novel feel so full of life is the chorus of voices that also come in. A Burning is also told through the eyes of PT Sir, Jivan’s old gym teacher, who is trying to move up in the world through the right-wing party and whose social climbing proves detrimental to Jivan’s case. We also hear from Lovely, a “hijra” (a transgender woman) who is treated as an outcast but who dreams of becoming a movie star. Lovely was one of Jivan’s students, and her voice has a particular, shining musicality: she always speaks in the present progressive, giving us a sense of continuation, of past events always unfolding and previous lives always lingering. This brilliant convergence is at the heart of A Burning, a novel you’ll likely consume in one sitting.

–Katie Yee, Book Marks Associate Editor

Diane Johnson, The True History of Mrs. Meredith and Other Lesser Lives

(NYRB)

Now, Diane Johnson is known for her Anglo-French novels of manners, Le Marriage, L’Affaire and Le Divorce. Few connect her with her earlier career as a biographer, and a revolutionary one at that. Lesser Lives, as Johnson’s 1972 book is commonly known, was one of the first biographies of the just as interesting wife of a famous man: Mary Ellen Peacock Meredith was married to the poet George Meredith and the brilliant and unconventional daughter of artist Thomas Love Peacock. Set solidly in the Victorian age, Johnson’s book asks why we have ignored people like Mrs. Meredith: “A lesser life does not seem lesser to someone who lived one,” and more of us lead lesser lives than the other kind. Johnson’s book opened up biography to include all kinds of lesser lives and minor characters who are just as fascinating as the famous people to whom they are adjacent.

–Lisa Levy, Lit Hub contributing editor