8 Books That Move Disability From the Margins to the Center

Katherine Dunn, Anne Finger, and Beyond

As a disabled writer, I’ve looked at how disability is represented in our literature for over two decades. This interest has taken me across the globe, with a special focus in disability representation in Japan, and more recently in Germany. Recently, at the behest of a writer colleague who was about to teach a class on writing with empathy (and inspired by the Bechdel Test), I came up with the Fries Test to measure the progress of disability representation. The questions of the Fries Test are purposefully basic, or as someone once commented, the bare minimum of how disability should be accurately represented in our literary culture. Here, I’ve compiled a list of texts that go further than that. These books move disability from the margins to the center, where they provide a critical lens to look at how we—disabled and nondisabled alike—live, or might live, our lives.

Geek Love, Katherine Dunn (1989)

A finalist for the National Book Award, Dunn’s novel is the story of the Binewski family, whose offspring are purposely born with various disabilities so they can perpetuate the family business—working in the circus. Dunn explodes what we think we know about disability. Her characters, such as Arturo the Aquaboy (who has flippers for limbs) and the conjoined twins Iphy and Elly, are incredibly complex in all their messy emotional and physical humanity. By placing disability in the historically important context of the freak show, Dunn not only gives us a startling look at humanity’s imperfections, but uses disability to give an insightful, sometimes scathing, look at family dynamics familiar to us all.

Mean Little Deaf Queer, Terry Galloway (2009)

Galloway’s memoir is funny, poignant, and, yes, mean. As the Lambda Literary review of this memoir says, “Blessedly, the disabled-child-as-hero is absent from Galloway’s history.” Galloway writes: “Passing as hearing took such a toll that passing as straight was a piece of cake.” She portrays herself as both oppressed and oppressor. She writes, “I might love the girls but I lusted for power.” Galloway gives us what we are rarely given in literature: a fully dimensional disabled person, warts and all.

Planet of the Blind, Stephen Kussisto (1998)

This memoir follows Kussisto’s movement from passing as sighted to accepting his identity as a blind person. Kussisto shows both the reasons for his wanting to pass as sighted and its foolish unworkability. He also redefines blindness from its usual depiction of total darkness. And by exquisitely employing his poetic skills—Kuusisto has also published books of poems—he allows the reader to imagine what it might be like if we lived in a world where being blind was no big deal:

On the planet of the blind no one needs to be cured. Blindness is another form of music, like the solo clarinet in the mind of Bartók . . . On the planet of the blind people talk about what they do not see, like Wallace Stevens who freely chased tigers in red weather. . . . The sighted are beloved visitors, their fears of blindness assuaged with fragrant reeds.

![]()

Elegy for a Disease: A Personal and Cultural History of Polio,(2010) and Call Me Ahab: A Short Story Collection, Anne Finger (2009)

Finger structures her memoir Elegy for A Disease as a dual history of a life lived with polio. By combining her personal history with that of the disease, she liberates the isolated disabled protagonist from typical narrative strictures, showing how sociopolitical myths, fears, and panic are an inextricable part of the disability experience. No longer is the heroine a lone figure fighting to survive a physical impairment—here we have disability defined as much by physical and social barriers.

This is also at the heart of Call Me Ahab, her short story collection. In what Finger calls “historical fictions of disability,” she places characters with disabilities center stage in events in which they are usually peripheral. For example, in “The Artist and the Dwarf,” she makes Mari Barbola, the dwarf depicted in Velazquez’s painting “Las Meninas” the protagonist of the story, giving us a truer history of Spain at that time.

The Still Point of the Turning World, Emily Rapp (2013)

In her best-selling memoir, Rapp turns the story of losing a son to Tay-Sachs disease into a thoughtful and philosophical look at parenting. The no-holds barred depiction of what it is like to have a child with a disability is distinguished not only by Rapp’s literary intelligence but also by her own disability experience, which she previously wrote about in Poster Child (2007). By employing the writings of C. S. Lewis, Sylvia Plath, and Hegel and drawing on works such as Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Rapp opens up what otherwise could be a claustrophobic and deservedly myopic story of her son Ronan’s life.

The Giant’s House, Elizabeth McCracken (1996)

This poignant and affecting novel about spinster librarian Peggy Cort’s love for James Sweatt, a younger man who was already 6’2” at eleven years old, can be seen as a counter to Diane Arbus’s famous 1970 photo, “The Jewish Giant at Home with His Parents.” Whereas Arbus’s giant is but a metaphor for our fear of difference—as well as the photographer’s own sense of herself as freakish—McCracken depicts the inner life of James Sweatt, as well as his life with his family, who welcomes Peggy into their fold. McCracken doesn’t shy away from the physical issues that beset James’s body as he grows older and taller. The humanity of this novel is breathtaking.

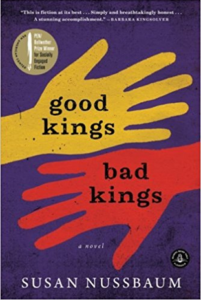

Good Kings Bad Kings, Susan R. Nussbaum (2013)

Playwright Nussbaum’s fiction debut, recipient of the Bellwether Prize for Socially Engaged Fiction, is told in the voices of seven diverse characters, patients or employees of an institution for adolescents with disabilities. 15-year-old Yessenia describes the situation succinctly: “I do not know why they send us all to the same place but that’s the way it’s always been and that’s the way it looks like it will always be because I am in tenth grade and I been in cripple this or cripple that my whole sweet, succulent Puerto Rican life.” Nussbaum gives voice to every character with an unsentimental vitality rarely matched in fiction.