6 Famous Writers Injured While Writing

When Making Stuff is Hazardous to Your Health

Even the toughest of poets and strongest of Hemingways would have to admit that “writer” is not a particularly dangerous job. (Unlike, say, fisherman, miner, logger, knife-thrower assistant.) Unless, that is, you count the risks of carpal tunnel and a sedentary lifestyle—which are real enough, but not exactly sonnet-worthy. Still, a few writers in history have actually suffered some serious health problems as a result of their writing practice—or in some cases, the drugs they used to fuel it. Below, you’ll find the stories of a few famous authors who found that writing was pretty hazardous, or even deadly. So perhaps the next time you sit down at your computer, you’ll remember to use caution. Maybe a life vest. Probably not amphetamines.

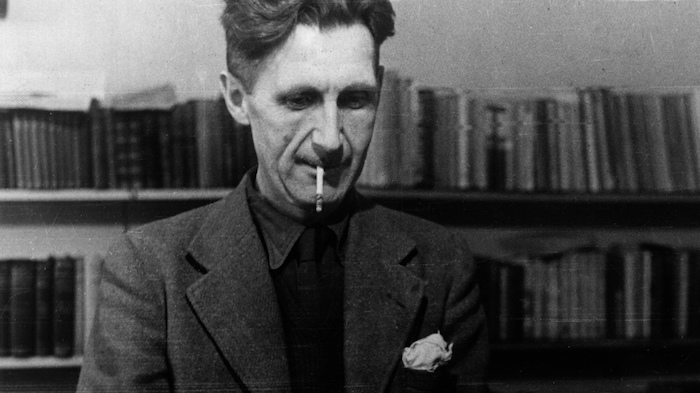

In Shakespeare’s Tremor and Orwell’s Cough: The Medical Lives of Great Writers, John J. Ross describes George Orwell’s “recurrent pattern of overwork and burnout.” Orwell struggled with health problems from childhood, and things were not improved when he was shot in the neck in Spain. But as Ross writes at PW, “his health collapsed for the first time after the writing of Homage to Catalonia, and the heroic effort of writing and revising Nineteen Eighty-Four would kill him.” As Ross notes, a line from Orwell’s essay “Why I Write” is significant here: “Writing a book is a horrible, exhausting struggle, like a long bout of some painful illness.” Indeed, in the process of writing the book, he got sicker and sicker: “He coughed up blood, had fever and night sweats, and lost 28 pounds in weight. The last two months of writing were done in bed.” He had developed the TB that would soon kill him.

Over at Poets & Writers, Anelise Chen notes that Herman Melville “dove with such intensity into his whale book that his entire family circulated letters conspiring to make him rest. Ignoring their pleas, he emerged from Moby-Dick plagued with eye spasms, anxiety attacks, and debilitating back pain.” John J. Ross quotes Melville’s wife Lizzie, who wrote that “this constant working of the brain, & excitement of the imagination, is wearing Herman out. . . [He is] toiling early & late at his literary labors & hazarding his health.” Nathaniel Hawthorne had a similar assessment, writing that his friend “no doubt has suffered from too constant literary occupation, pursued without much success, latterly; and his writings, for a long while past, have indicated a morbid state of mind.”

The nineteenth-century Italian poet Giacomo Leopardi, whom Adam Kirsh has dubbed “the supreme poet of passive, helpless suffering,” may have turned out that way because he from debilitating scoliosis, which gave him a hump and turned him into, as he put it, “a walking sepulcher.” He blamed his condition on his “scholarly excesses”—read: writing too much—and once wrote, “I have woefully and incurably ruined myself for the rest of my life, rendering my appearance terrible and despicable to most people.” All in the service of his writing, which, despite the fact that he died before his 40th birthday, is ranked among the best of his time.

Honoré de Balzac was famously addicted to coffee, which he loved for what it did for his writing. He drank it in large amounts to fuel his creative work, until finally, as he explains in his essay “The Pleasures and Pains of Coffee,” resorting to eating cold coffee grounds on an empty stomach for maximum effect:

This coffee falls into your stomach, a sack whose velvety interior is lined with tapestries of suckers and papillae. The coffee finds nothing else in the sack, and so it attacks these delicate and voluptuous linings; it acts like a food and demands digestive juices; it wrings and twists the stomach for these juices, appealing as a pythoness appeals to her god; it brutalizes these beautiful stomach linings as a wagon master abuses ponies; the plexus becomes inflamed; sparks shoot all the way up to the brain. From that moment on, everything becomes agitated. Ideas quick-march into motion like battalions of a grand army to its legendary fighting ground, and the battle rages. Memories charge in, bright flags on high; the cavalry of metaphor deploys with a magnificent gallop; the artillery of logic rushes up with clattering wagons and cartridges; on imagination’s orders, sharpshooters sight and fire; forms and shapes and characters rear up; the paper is spread with ink—for the nightly labor begins and ends with torrents of this black water, as a battle opens and concludes with black powder.

It’s not for everyone, of course. Balzac cautions that he once recommended his special method to a friend who was desperate to get some work done—but the friend was “tall, blond, slender and had thinning hair,” and it did not go at all well. Neither did it go perfectly well for Balzac himself, who reportedly died of caffeine poisoning at the age of 51.

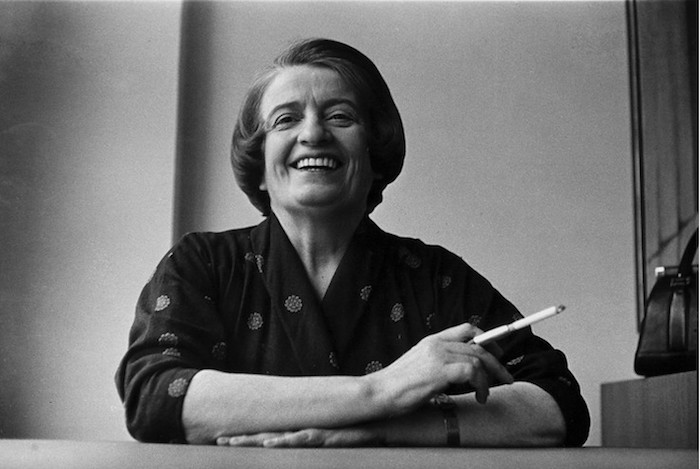

Objectivist Ayn Rand also had an addiction that sprang from her writing process: amphetamines. After selling The Fountainhead to Knopf in 1938, Rand found herself unable to finish it by the publisher’s deadline—even after a year’s extension, she was only a quarter of the way through. In 1940 Knopf dropped the book, and no one else would publish it either. Rand wound up firing her agent and finally getting in touch with Archibald Ogden, an editor at the Bobbs-Merrill Company, who basically forced his bosses to let him buy the book. Again, she had just over a year to finish it. It was then she turned to Benzedrine, which allowed her to write at an unprecedented clip, and she finally turned in the completed manuscript, one day before the deadline. But there were costs to her newfound productivity. Rand’s reliance on the drug led to “mood swings, irritability, emotional outbursts, and paranoia,” and according to biographer Jennifer Burns, “by the time the book was complete Rand’s doctor diagnosed her as close to a nervous breakdown and ordered her to take two weeks of complete rest.”

If you’re familiar with his work, it isn’t particularly surprising to find out that Franz Kafka put himself through emotional and physical hell to get his writing done. As Zadie Smith outlined it in The New York Review of Books:

At the Assicurazioni Generali, Kafka despaired of his twelve-hour shifts that left no time for writing; two years later, promoted to the position of chief clerk at the Workers’ Accident Insurance Institute, he was now on the one-shift system, 8:30 AM until 2:30 PM. And then what? Lunch until 3:30, then sleep until 7:30, then exercises, then a family dinner. After which he started work around 11 PM (as Begley points out, the letter- and diary-writing took up at least an hour a day, and more usually two), and then “depending on my strength, inclination, and luck, until one, two, or three o’clock, once even till six in the morning.” Then “every imaginable effort to go to sleep,” as he fitfully rested before leaving to go to the office once more. This routine left him permanently on the verge of collapse.

This weakened state may or may not have played a role in his contraction of laryngeal tuberculosis and its subsequent ravages on his body, so it’s too much to say his work killed him, but it certainly seems relevant. His throat closed up, precluding the ingestion of any food, and so he technically died of starvation, working on his story “The Hunger Artist” to the very last.

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.