50 Facts About The Power Broker to Celebrate Its 50th Anniversary

In Which James Folta Refuses to Write to a Listicle

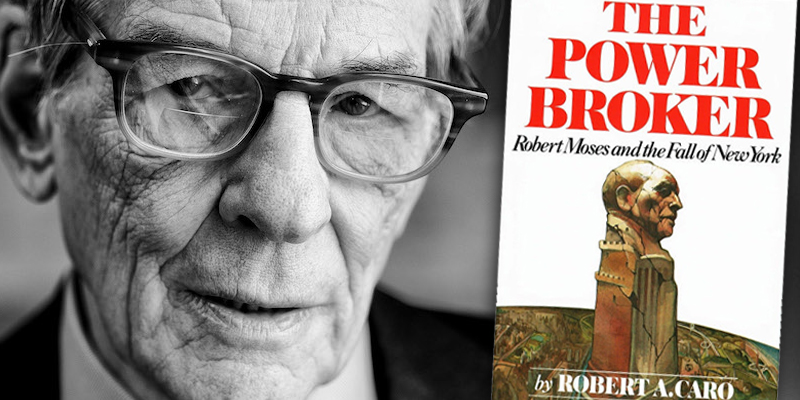

Today is the 50th anniversary of the release of Robert Caro’s The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York (Fact #1). The book remains incredibly popular—it’s currently in its 74th printing and has has never been out of print in hardcover or paperback (#2), despite Caro initially believing the naysayers who said no-one would be interested: “…I really did believe what people said, that nobody would read the book. I did believe that.”

People not only read it, but praised it: The Power Broker won the Pulitzer Prize for biography and the Francis Parkman Prize for American history, and was a finalist for the National Book Award (#3). Every book Caro’s written has appeared on the cover of The New York Times Book Review, a perfect six-for-six record (#4). And culturally, the book is an institution: there are podcasts about it, games about it, a play about it, and Caro even “appeared” (played by comedian Alex Fernie) on a recent episode of the comedy show Comedy Bang Bang.

People book-club The Power Broker, pundits give it a prominent place in their Zoom backgrounds, and completing the book is something to brag about—at the New York Historical Society Museum’s special exhibition celebrating the book’s 50th anniversary, you can buy cheeky “I Finished The Power Broker” mugs.

I’m one of those Caro-crazed obsessives who has read everything he’s written—the books are well worth your time, and there’s no better place to start than this volume on Robert Moses, an unelected, and nearly unknown figure who nonetheless managed to build so many roads, bridges, and parks that he fundamentally changed America’s largest city.

Caro’s books are about power, how it is controlled and deployed by individuals and institutions, and what it reveals in those who manage to get it. Caro was inspired by early brushes with the powerful. After graduating from Princeton, he briefly worked as a speechwriter and PR man for a Democratic Party boss in New Brunswick, New Jersey, but was so disgusted by the way the elected official was treating Black people, that he walked away from that job, and working in politics, forever (#5).

Caro first wrote about Moses as a journalist for Newsday, writing a series of articles about the wrong-headedness of a planned bridge across the Long Island Sound (#6). His piece was widely praised as being persuasive, but to no avail, as he told The Times:

“This was the world’s worst idea,” he told me. “The piers would have had to be so big that they’d disrupt the tides.” Caro wrote a series exposing the folly of this scheme, and it seemed to have persuaded just about everyone, including the governor, Nelson Rockefeller. But then, he recalled, he got a call from a friend in Albany saying, “Bob, I think you need to come up here.” Caro said: “I got there in time for a vote in the Assembly authorizing some preliminary step toward the bridge, and it passed by something like 138-4. That was one of the transformational moments of my life. I got in the car and drove home to Long Island, and I kept thinking to myself: ‘Everything you’ve been doing is baloney. You’ve been writing under the belief that power in a democracy comes from the ballot box. But here’s a guy who has never been elected to anything, who has enough power to turn the entire state around, and you don’t have the slightest idea how he got it.’ ”

His Newsday writing earned him a Nieman Fellowship at Harvard where he continued to investigate power (#7). He studied government and urban planning, but started to see urban planning’s technocratic analysis of what gets built and why, as hopelessly naive: “‘This is completely wrong. This isn’t why highways get built. Highways get built because Robert Moses wants them built there.”

Caro knew he was onto something, but that it needed to be longer than a newspaper would allow, so he wrote a proposal letter that landed with an editor at Simon & Schuster. The editor wanted a book on suburbia, but Caro insisted and was signed to a two-year, $5,000 contract for a manuscript on Robert Moses (#8).

It would take him seven years to finish the book (#9), and anyone who has seen it on a shelf can see why: The Power Broker is a hefty 1,344 pages long (#10). The depth of Caro’s writing begins in his rigorous, frankly overwhelming research process. He read thousands of documents and conducted 522 interviews for the book, (#11) everyone from a reluctant Moses down to each and every social worker who was employed at the camp run by Robert Moses’ parents (#12). He and his wife Ina—the only research assistant he’s ever worked with (#13)—interview people over and over for his books, knowing that they’ll get something new each time.

Working on The Power Broker in the ‘60s meant a lot of wading through paper. The archives were a physical challenge—Caro injured his back in a basketball game early in his research on Moses, so Ina did a lot of the critical shoe leather work in 1967 (#14). (Ina is often mentioned as his wife and assistant, but she’s a writer and historian too, and wrote a book about experiencing French history by train.)

Caro is thorough because he doesn’t want to miss a single thing. He often cites the advice he got from the managing editor when he was a journalist at Newsday: “Turn every goddamn page.”

But research is only part of Caro’s process; his writing is similarly rigorous. Caro is a relentless outliner and re-outliner, which always focus around a kernel that informs the whole book. As he told The Paris Review:

So before I start writing, I boil the book down to three paragraphs, or two or one—that’s when it comes into view. That process might take weeks. And then I turn those paragraphs into an outline of the whole book…Then, with the whole book in mind, I go chapter by chapter.

This simplifies things for him: “…if you can figure out what your book is about and boil it down into a couple of paragraphs, then all of a sudden a mass of other stuff is much simpler to fit into your longer outline.”

He doesn’t often follow that outline though, and over and over in Caro’s books, sections that he planned as chapters end up expanding into entire volumes. His books scale out like fractals, expanding and pushing out into different topics.

This tunneling and informative digression is one of the things that make his books so good. They are focused in thesis, but explored in ranging execution. The Power Broker contains sections on the geology and ecology of Long Island, New York State government, and Governor Al Smith (#15). And these aren’t mere footnotes—Caro often spends a hundred pages on these “off-topic” subject—but they always prove to be instrumental to understanding some aspect of the larger story.

This may sound like an inundating, firehose approach, but Caro is a gorgeous writer and is as attentive to the construction of his sentences as he is to his narratives. Caro’s longtime editor Robert Gottlieb said in an interview that, “A semicolon matters as much as, I don’t know, whether Johnson was gay.”

It’s a novelist’s approach, with a deep attention to pacing and word choice. In an interview with The Paris Review, Caro describes finding inspiration in The Iliad:

For instance, Moses built 627 miles of roads. I said, Come on, that’s just a bare statement of fact—how do you make people grasp the immensity of this? And I remembered reading the Iliad in college. The Iliad did it with lists, you know? With the enumeration of all the nations and all the ships that are sent to Troy to show the magnitude and magnificence of the Trojan War. … So in the introduction to The Power Broker, I tried listing all the expressways and all the parkways. I hoped that the weight of all the names would give Moses’s accomplishment more reality. But then I felt, That’s not good enough. Can you put the names into an order that has a rhythm to it that will give them more force and power and, in that way, add to the understanding of the magnitude of the accomplishment? … Rhythm matters. Mood matters. Sense of place matters. All these things we talk about with novels, yet I feel that for history and biography to accomplish what they should accomplish, they have to pay as much attention to these devices as novels do.

This particularity around his writing hasn’t made his writing life any easier though. One of Caro’s big fights around edits was with The New Yorker, which ran a truncation of The Power Broker as a four-part series in 1974 (#16), with amazing Saul Steinberg illustrations (#17). Caro thought the magazine would run excepts, but instead, The New Yorker compressed the whole book, taking his nearly quarter of a million words down to around 100,000 (#18). Caro was not happy, and complained that the magazine edited his project to death, “They softened my style.” The fight became so intense between Caro and editor-in-chief William Shawn “that between the second and third installments there was a weeklong gap, unthinkable in those days, while the two sides stared each other down.”

Caro ultimately won enough semicolon fights that he let the series conclude. It was a boon for the struggling writer: the check that Caro got from The New Yorker was more than what he’d been paid for the book up until that point (#19). Caro and Ina used the money to take a trip to Paris, a trip he had promised they’d take when the book was finished (#20).

And by 1974, Ina had been waiting a long time for that trip. Caro thought he could finish The Power Broker in nine months, but it took him seven years, three publishers, and two editors (#21). One chapter alone—“The Mile,” which documents hundreds of families displaced to build one mile of expressway—took Caro six months to research and write. (#22)

Writing The Power Broker also nearly bankrupted him. The advance for the book was $5,000, but he ran through that in a year and was nowhere near finished (#23). Desperate for more time, Ina sold their house on Long Island and they moved to an apartment in the Bronx, planning to live off the $25,000 they made on the house for a year (#24).

But that ran out too, with Caro having written half a million words that only covered half of Moses’ story (#25). Simon & Schuster gave him another $1,500, but around the time that was spent, Caro’s editor left to work on his own book (#26). Caro jumped at the chance to take his book elsewhere, and began searching for an agent to land him an editor and money. He ended up with Lynn Nesbit, who told him money was no problem, “‘You can stop worrying about that right now,” Nesbit told him. “I can get you that by just picking up this phone. Everybody in New York knows about this book’” (#27).

At this point, Caro was five years and a million words into the project, and finally felt financially stable. This time was necessary; Caro had always been a long writer, and it’s rumored that his college thesis on existentialism in Hemingway was so long that Princeton’s English department set a limit on how many pages senior theses could run (#28).

But no one wanted a million-word book from a first-time writer. Enter Robert Gottlieb, Caro’s longtime editor and the man who cut him down to size, who Nesbit connected Caro with (#29). Gottlieb cut 350,000 words from The Power Broker manuscript (#30), with Caro fighting him every step of the way. He told The Daily Beast that two entire chapters were cut (#31),

One was on Jane Jacobs stopping the Lower Manhattan Expressway. And one was why the New York City Planning Commission has no power so that someone like Robert Moses could run over the Planning Commission. Those are very significant things. Today I get asked a lot about both those subjects, and then I always have a pang of regret that they’re not in The Power Broker.

Caro’s fights with Gottlieb are legendary, and sometimes became so contentious that Caro had to retreat to the men’s room at Knopf to cool off (#32). The two became close, though—and the documentary Turn Every Page is in large part an homage to their long-lasting relationship.

The process of working on such a long book was a physical issue too. Caro couldn’t lug all that paper around during the year his back was injured (#33), and even when he recovered, he needed help carrying it:

…there came a point when I had to bring the manuscript in, and it was in seven typewriter boxes. Ina drove me in, I got out of the car, and [the boxes] just reached up to my chin. Seven boxes. And I’m in the elevator going up. This man I’ve never met — Tony Schulte — says to me, ‘Is that a manuscript in there?’ I said, ‘Yes.’ And he said, ‘How many copies?’ And I said, ‘One copy.’

Back in the ‘70s that Knopf employee may have rolled his eyes at Caro, but today people would line up to carry those boxes. Caro has an army of super-fans: Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg has referenced The Power Broker (#34), and President Obama cited the book as an influence:”’I think about Robert Caro and reading The Power Broker back when I was 22 years old, and just being mesmerized, and I’m sure it helped to shape how I think about politics’” (#35).

One of Caro’s nerdiest fans is comedian Conan O’Brien: “‘The Lyndon Johnson books by Caro, it’s our Harry Potter,’ Mr. O’Brien said. ‘If there were over-large ears and fake gallbladder scars that we could wear instead of wizard hats while waiting in line to get the book, we would do it’” (#36).

Conan spent years trying to book the historian as a late night guest for years, but Caro always politely declined (#37). Conan was afraid he would get scooped:

In his morbid fantasies, he imagines Mr. Caro appearing on “The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon,” where the guests often play games with the host.

“I know that someday I’m going to turn on Fallon and see Caro playing Pictionary,” he said. “And I’m just going to be enraged. He’s going to get everyone cheering, and Cardi B’s there, high-fiving him. And I’m just going to be enraged.”

Caro finally sat down for an interview on Conan’s podcast (#38) while promoting his latest book Working—Conan thanked the historian for “finally writing a book that’ll fit on my night table.”

Today, Caro is finishing the final volume of his “Years of Lyndon Johnson” series. By all accounts, his process is the same as it was when he was writing Power Broker; Caro dresses in a jacket and a tie, and writes out his drafts in pencil, favoring the brand he used as Newsday journalist (#39). Once he has nearly a half-dozen drafts done by hand (#40), he starts typing on a Smith Corona Electra 210 (#41), double-spacing so that he can continue to edit by hand. The Smith Corona he uses is no longer being produced, but fans have sent him so many old ones that in 2019, he had 11 extras on hand to raid for parts (#42).

Caro rarely uses a computer (though the Johnson presidential library made him use a laptop after staff complained about the clacking of his typewriter [#43]) and for many years, he didn’t have an email address (#44).

He worked on The Power Broker for year at Columbia University, thanks to a Carnegie Foundation fellowship (#45), then in a small office in the basement of an apartment building on Johnson Avenue in the Bronx (#46), and finally in the prestigious Frederick Lewis Allen Memorial Room, a collective space at the New York Public Library (#47).

Now he writes at an office on 57th Street or at a shed in his Long Island backyard, and both writing spaces have a custom desk (#48) that Time magazine described as having, “a rounded notch, a clean little half circle that lets him snug his wooden chair into his custom-made workstation. Instead of legs, the top rests on a pair of sawhorses.” The height of the desk was “calibrated by President John F. Kennedy’s personal physician, Janet G. Travell, M.D., a specialist in back pain” (#49).

I imagine that’s where Caro is today, right now perhaps, surrounded by his outlines, transcribed interviews, and spare typewriters, working away on his final volume on LBJ—a project he’s been working on for nearly as long as Johnson was alive (#50).

But all the effort, over all those years, has led to stunning writing. 50 years on, The Power Broker is still fascinating and urgent, and it’s why so many of us can’t wait to read his final volume on LBJ. It’s like waiting on George R.R. Martin, but for a different kind of nerd.

Will he finish? Some have speculated that, for various psychoanalytical reasons, Caro maybe doesn’t want the project to end, that the idea of handing in a final manuscript is too hard for him to face. Caro says no:

“That’s ridiculous. You couldn’t want anything more than I want to be finished with this book.”

James Folta

James Folta is a writer and the managing editor of Points in Case. He co-writes the weekly Newsletter of Humorous Writing. More at www.jamesfolta.com or at jfolta[at]lithub[dot]com.