5 Novels by Singaporean Writers You Should Read

A Historical Drama, a Time-Traveling Love Story, and More

As a Singaporean living abroad, something you lose count of is the number of times you’ve been asked about chewing gum. You explain for the nth time that yes, it is illegal to import gum into Singapore, and while addressing the inevitable questions that follow (no, you will not be arrested for bringing a stick of gum through customs, yes, dental gum can be obtained from dentists), you go through the list of things you wish you could talk about instead.

You wish you could talk about the hawker food, the way your friends are evangelical about their favorite chicken rice stalls, the split between those who believe rice should be subtly flavored and those who prefer each grain slicked and coated in yellow chicken fat. You wish you could talk about the government campaigns whose posters and mascots chart the years of your childhood: the National Courtesy Campaign; the Speak Good English Movement; the Clean & Green Initiative. You wish you could talk about the time you were watching Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End as a teenager and everyone in the movie theater cheered when Chow Yun Fat said “Welcome to Singapore.” How it felt like a sudden shock to have the name of your little country, a country the size of New York City, to be said on screen in a big budget Hollywood movie. How it made you wonder, many years later, why it should feel like a shock at all.

Only one of the five novels on this list, Sharlene Teo’s Ponti, is actually set in Singapore. But I believe that Singapore shimmers beneath the surface of the geographically varied, otherworldly settings of the remaining four.

A Singaporean writer myself, it wasn’t until asked by an interviewer about how growing up in Singapore had influenced my work that I realized I’d been writing about home all along. My own novel, Suicide Club, is set in a dystopian, near future New York, where life expectancies average 300 years. But the ideas it deals with—state paternalism, metric-driven notions of success and the darker side of meritocracy—had all been deeply inspired by my upbringing. Thea Lim similarly attributes the themes of loss in her novel, An Ocean of Minutes, to Singapore’s racing modernity and what often feels like a tenuous relationship with the past; to the unsettling way old buildings and streets back home have a habit of vanishing without a trace.

Amongst the novels on this list, you will find a historical drama set in early Maoist China, a time-traveling love story that takes place in virulent flu-swept America, a silkpunk universe where genders are not assigned at birth. In 2018, Singaporean writers are tackling topics of loss, familial love, memory, female friendships. And I am happy to say that no one is writing about chewing gum.

Clarissa Goenawan, Rainbirds

(Soho Press)

Set in an imagined town outside Tokyo, Clarissa Goenawan’s dark, spellbinding literary debut follows a young man’s path to self-discovery in the wake of his sister’s murder.

Named one of 2018’s most anticipated reads by The Huffington Post and Bustle, Rainbirds “evokes the simple joys of early Haruki Murakami” (amNewYork) and is “a soulful whodunit full of deadpan humor and whimsical narrative unpredictability” (Kirkus Reviews).

Kirsten Chen, Bury What We Cannot Take

(Little A)

Set against the backdrop of 1950s China, Bury What We Cannot Take tells the story of a family forced to flee their home after a nine-year-old boy reports his grandmother vandalizing a framed portrait of Chairman Mao.

Bury What We Cannot Take has been named one of 2018’s most anticipated reads by Electric Literature, The Millions, The Rumpus, Harper’s Bazaar, and InStyle. Celeste Ng calls it “an engrossing historical drama and a nuanced exploration of how far the bonds of familial love can stretch.”

Thea Lim, An Ocean of Minutes

(Touchstone)

In 1981 a deadly flu pandemic flays America, and to pay for her lover Frank’s treatment, Polly takes a job elsewhere: the future. But when Polly reaches 1998, she’ll have to risk everything to find Frank again. An Ocean of Minutes asks: how much does it cost to hold on to the past, and how much does it cost to let go?

A “strikingly imaginative time-travel story” (Elan Mastai), An Ocean of Minutes has been likened to The Time Traveler’s Wife and Station Eleven.

JY Yang, The Descent of Monsters (The Tensorate Series)

(Tor)

The third novella in Yang’s silkpunk fantasy world of The Tensorate Series, The Descent of Monsters follows an investigation into atrocities committed at a classified research facility that threaten to expose secrets that the Protectorate will do anything to keep hidden.

Lauded as “joyously wild stuff” by The New York Times, the Tensorate Series has been described as “full of love and loss, confrontation and discovery” (Ken Liu) and “wonderfully imaginative and original” (Aliette de Bodard). One of the earlier novellas in the series, The Black Tides of Heaven, has been nominated for a 2018 Nebula Award.

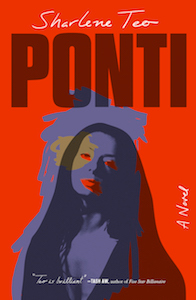

Sharlene Teo, Ponti

(Simon & Schuster)

Set in Singapore, Ponti is the story of three women: 16-year-old Szu; her mother Amisa, a once beautiful actress; and Circe, Szu’s unlikely friend and confidant. Spanning five decades of their interconnected lives, Ponti is about a book about friendship, memory, and how we change.

The winner of the inaugural Deborah Rogers Writers Award in 2016, Ponti has been called “remarkable” by awarding judge Ian McEwan and compared to novels of Zadie Smith and Elena Ferrante. Tash Aw raves: “Sharlene Teo has produced not just a singular debut, but a milestone in South East Asian literature.”

Rachel Heng

Born and raised in Singapore, Rachel Heng is the author of the novel Suicide Club, translated into ten languages and The Great Reclamation. Her short fiction has appeared in The New Yorker, Glimmer Train, McSweeney’s, and elsewhere. She received her MFA from the Michener Center for Writers and has received grants and fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, Sewanee Writers’ Conference, and the National Arts Council of Singapore, among others. She is currently an assistant professor of English at Wesleyan University.