5 Books You May Have Overlooked in April

From London Housing Estates to a Broken America 500 Years in the Future

Modern multiracial London, a Caribbean colonial sugar plantation, an undefined afterlife, pre-WWII England, and a dystopian United States—this month’s overlooked fiction will transport you whether you like it, or not.

Guy Gunaratne, In Our Mad and Furious City

Gunaratne’s In Our Mad and Furious City takes place in 48 hours on a London housing estate. What makes a community when everyone in it belongs to a different group—ethnic, religious, cultural? The answer is friendship, and Gunaratne’s protagonists Selvon, Yusuf, and Ardan hold loyalty for each other even when they have given up on their individual futures. Put down your Julian Barnes and your Zadie Smith and whomever you read last year—this is British literature today.

Jenny Jaeckel, House of Rougeaux

Starting in 1785, House of Rougeaux by Jenny Jaeckel follows an enslaved family on a Martinique sugar estate—you may never eat the refined white stuff again after reading. While Jaeckel writes bluntly about the horrors of this particular colonialism, her main focus is the bond between siblings Abeje and Adunbi, a bond that unites them through being orphaned and finally, when a long-held secret is unearthed, helps the Rougeaux family understand its deep legacy. Jaeckel’s graceful prose and clear purpose make this an excellent addition to historical novels about the French Caribbean.

Laura Lindstedt, Oneiron (Trans. Owen Witesman)

Lindstedt won her country’s 2015 Finlandia Prize. She also won that Prize in 2007 for her debut novel, Scissors, so let’s pay attention to her work. In this multi-genre (prose, poetry, essay) work, Lindstedt places seven women together seconds after they’ve departed the earth. Where are they? All the women know is that time has ceased to exist. Together, through different kinds of storytelling, they are able to figure out how they are connected and how they are each meaningful. Lindstedt’s writing can be visceral to the point of shock, not because anything she describes is horrific or vulgar, but because she juxtaposes life’s extremes (orgasm, elimination) with death’s lacunae.

Heidi Sopinka, The Dictionary of Animal Languages

The Dictionary of Animal Languages is a fresh, unexpected debut novel inspired by the life of Leonora Carrington, English-born but Mexican-identified, an artist whose life has too often been defined solely by her relationships with famous men, including the surrealist painter Max Ernst. Sopinka focuses on Carrington in her nineties, when the defiant woman has severed all ties to society in order to complete the great work of the title—but learns that there may be one tie she can’t shake loose. This novel, like Claire-Louise Bennett’s Pond, resides so purely in showing and not telling that Carrington’s great age and iconic roles slip away; readers are suspended in her experience. Highly recommend.

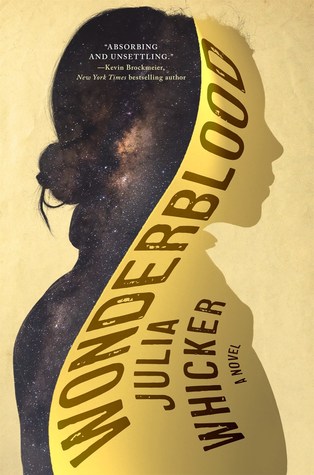

Julia Whicker, Wonderblood

Although Wonderblood has received praise in the trades, there’s not enough chatter about it: This novel is a dystopian’s dystopia, a fabulist’s fable, about a United States 500 years in the future that’s been decimated by disease. Survivors worship space-shuttle ruins and make pilgrimages to Cape Canaveral. Strange, amateurish, black-and-white watercolors separate chapters, illustrating stages in protagonist Aurora’s journey with the mysterious Mr. Capulatio. Reminiscent of Gormenghast in its world-building but far more political in its intent, Wonderblood is a book that might be talked about for some time, if enough people pick it up and enter its eerie world.

Bethanne Patrick

Bethanne Patrick is a literary journalist and Literary Hub contributing editor.