5 Books Making News This Week: Technology, Buddhism, and Thrillers

Ellen Ullman, Robert Wright, Christopher Bollen, and More

Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards go to Isabel Allende for lifetime achievement, Peter Ho Davies’ The Fortunes and Karan Mahajan’s The Association of Small Bombs (fiction), Tyehimba Jess’s Olio (poetry) and Margot Lee Shetterly’s Hidden Figures (nonfiction). Carl Sandburg Literary Awards go to Margaret Atwood and Dave Eggers. The James Tait Black Award is shared by Eimear McBride, for her novel The Lesser Bohemians, and Laura Cumming for her biography The Vanishing Man: In Pursuit Of Velazquez.

Paul Yoon’s new story collection launches with starred reviews from PW, Kirkus and Library Journal, tech pioneer Ellen Ullman is back with another deep dive into life in coding, artist Emma Reyes writes an “incredible” inadvertent memoir, Christopher Bollen’s latest thriller “positions him as a worthy successor to Patricia Highsmith,” and Robert Wright has a new take on mindfulness meditation that might help those mired in political polarity.

Paul Yoon, The Mountain

Six stories set in the past, present and future in various locations—Shanghai and South Korea, upstate New York, Vladivostok, Galicia among them—from Yoon, a winner of the National Book Foundation’s 5 under 35 Award and author of the novel Snow Hunters and the story collection Once the Shore. The enthusiasm begins when The Mountain earns starred reviews from PW, Kirkus and Library Journal.

“The stories in Paul Yoon’s . . . story collection are told with a placidity that belies their violence,” writes Mark Athitakis (Minneapolis Star-Tribune).

“Reading The Mountain is like admiring a glowing sunset before realizing that what you’re really watching is a wildfire heading your way. Children are shot. Men are blown up. Addiction and displacement abound. And yet Yoon maintains a gentle tone, not to soften his characters’ troubles but to encourage us to see them differently.”

Ilana Massad (Los Angeles Times) points out, “The characters peopling these pages share certain commonalities: as children, most were raised by one parent, with the other dying or abandoning the family; their adulthood is full of nostalgia for childhood intimacy; their shaky memory is impeded by sometimes unspecified trauma; and their friendships are rare and tend to end violently.”

Kevin Nguyen (GQ) concludes, “To some, Yoon’s subtlety might come across more as sleepy, but for the patient, there’s plenty to unravel in his tightly wound stories. Both careful and confident, The Mountain shows that a classic approach to a classic form can still feel vital and relevant when in the hands of a perfectionist like Paul Yoon.”

Ellen Ullman, Life in Code

Writing code, writes Ullman, is “an illness, a fever, and obsession. It’s like riding a train and never being able to get off.” Her first book, Close to the Machine: Technophilia and Its Discontents, published in 1997, detailed her work as a programmer. After two decades as one of the rare females in the digital world (and the author of two novels), she’s still a refreshingly authentic voice for the joy of computing. “I am dedicated to changing the clubhouse,” she tells The New Republic’s Anna Wiener. “The way to do it, I think very strongly, is for the general public to learn to code . . . It’s coding as populism: Self-education as a way to shift power in an industry that is increasingly responsible for the infrastructure of everyday life.”

Life in Code “manages to feel like both a prequel and a sequel to her first book,” notes J.D. Biersdorfer (New York Times Book Review). “The technology mentioned within those early chapters often recalls quaint discovery, like finding a chunky, clunky Nokia cellphone in the back of the junk drawer. The piece on preparing computers for the Year 2000 has a musty time-capsule feel, but the philosophical questions posed in other chapters—like those on robotics and artificial intelligence—still resonate.”

Life in Code, writes Laura Miller (Slate), marks Ullman’s “long-awaited return to the themes that first made her name: what it’s like to share our world with sophisticated machines; the myriad, nearly undetectable ways that they change us; and the fundamental ways they cannot. One of the book’s highlights is a long, reported look at the idea of artificial life, and it ends with a perceptive, respectful and wholly unsentimental tribute to Ullman’s late cat, Sadie.”

Leah Greenblatt (Entertainment Weekly) calls Life in Code “a consummate insider’s take, rich with local color and anecdotes.” It’s “illuminating and unfailingly clever,” she adds, “but above all it’s a deeply human book: urgent, eloquent, and heartfelt.”

Emma Reyes, The Book of Emma Reyes, tr. Daniel Alarcon

Raised in poverty in Bogotá, Emma Reyes grew up to be an artist living in Paris in a circle that included Frida Kahlo and other Latin American luminaries. Her writing was praised by Gabriel Garcia Marquez (although she stopped writing the letters that form the basis of her memoir for two decades because her correspondent showed them to Marquez, breaching her confidence).

“Hers is an incredible biography by any measure, but the book’s most startling element is Reyes’s clear-sighted, unsentimental remembrance of her difficult childhood,” writes Nicole Rudick (Paris Review). “The narrative comes in the form of 23 epistolary sketches written by Reyes between 1969 and 1997 to her friend, the critic and historian Germán Arciniegas. (He once showed them to García Márquez, who effused about them to Reyes herself; furious with Arciniegas’s breach of privacy, she didn’t write him another letter for some 20 years.) Reyes is gloriously unceremonious in her telling: the memoir begins in a garbage heap and ends with a dog sniffing another’s behind.”

John Williams (New York Times) points out, “The most sophisticated aspect of this book, conceived as an amateur’s project—‘she wanted the book to be published with errors,’ the editor Felipe González once said; ‘she cultivated her mistakes’—is just how meticulously Reyes maintains the perspective of a child throughout. When she remembers how one nun taught her that Jesus ‘wasn’t on the earth anymore,’ and had ‘gone to live with his rich dad who was in the clouds,’ it’s as if we are the child learning this lesson.”

“Her writing is exceptional,” writes Lily Meyer (NPR). “Several times while reading, I gasped out loud at the beauty of her prose. It’s some of the best writing I’ve read in years.”

Christopher Bollen, The Destroyers

In Bollen’s tense literary thriller, his narrator tracks down his boyhood friend, the son of a wealthy Greek-Cypriot businessman, on the Greek island of Patmos. Almost at once his search for opportunity turns dangerous. Critics approve.

Art Taylor (Washington Post) writes, “Bollen . . . reveals a graceful prose style in his literary thriller. Sharp imagery and incisive descriptions bring to life both the Greek island of Patmos and the moneyed class laying claim to it: tourists ‘lingering between states of hangover and hunger,’ ‘ochre bodies fashionably starved’ and dancers swaying in ‘slow, narcotic movements.’ Heat pours through ‘the white hole of noon,’ and on the Aegean, ‘darkened yachts look like flies crawling on raw, blue meat.’ As the images and commentary suggest, paradise isn’t quite what it seems, especially amid Greece’s austerity crisis and an influx of Syrian refugees.”

“The Destroyers is built of a tension almost sexual in its luxuriousness,” notes B. David Zarley (Paste). “It’s all gleaming seas and waxed wooden decks, the warmth of burned flesh and vodka, the metallic taste of blood and lucre, with the effortless indomitability of a yacht bobbing along a bleached-bone dock.”

Bollen’s second literary thriller “positions him as a more than worthy successor to Patricia Highsmith,” writes Lucy Scholes (The National).

Thad Ziolkowski (New York Times Book Review) concludes:

Bollen demonstrates a generally sure hand with the thriller’s death-propelled events, which frees him to explore afresh certain timely (and timeless) themes: the constraints on friendship in adulthood, the double-edged sword of money in its scabbard of family, and—especially—the weightless coming to terms with no longer being young. This novel’s motto could almost have come from Sophocles: Youth, which the gods adore, dies at 29.

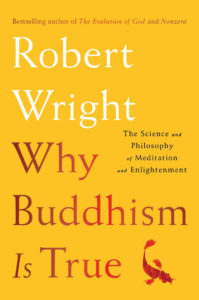

Robert Wright, Why Buddhism Is True

“Buddhist practice, once seen as subversive and countercultural, now looked like a capitalist tool,” Wright points out in his new book (already a New York Times best seller). “It had gone from deepening your insight to sharpening your edge.” In a podcast with Isaac Chotiner (Slate), Wright suggests that secular Buddhism and meditation are a “program for seeing the world more clearly” and an aid for those mired in political polarity. His emphasis on the practical and the scientific resonates with critics.

“The goal of Why Buddhism Is True is ambitious,” notes Antonio Damasio (New York Times Book Review): “to demonstrate ‘that Buddhism’s diagnosis of the human predicament is fundamentally correct, and that its prescription is deeply valid and urgently important.’ It is reasonable to claim that Buddhism, with its focus on suffering, addresses critical aspects of the human predicament. It is also reasonable to suggest that the prescription it offers may be applicable and useful to resolve that predicament. To produce his demonstrations and to support the idea that Buddhism is ‘true,’ Wright relies on science, especially on evolutionary psychology, cognitive science and neuroscience. This is a sensible approach, and in relation to Buddhism it is almost mainstream.”

Adam Gopnik (The New Yorker) writes, “The dwindling down of Buddhism into another life-style choice will doubtless irritate many, and Wright will likely be sneered at for reducing Buddhism to another bourgeois amenity, like yoga or green juice . . . Yet what Wright is doing seems an honorable, even a sublime, achievement. Basically, he says that meditation has made him somewhat less irritable. Being somewhat less irritable is not the kind of achievement that people usually look to religion for, but it may be as good an achievement as we ought to expect.”

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.