5 Books Making News This Week: Returns, Refugees, and Religious Cults

Inara Verzemnieks, Lawrence Osborne, Rebecca Stott, and More

Award-winning biographer Hermione Lee lauds Graham Swift, winner of the venerable but secretive Hawthornden Prize. Edwidge Danticat’s new book interweaves memoir and literary criticism, Laura Dassow Walls gives us a fresh perspective on Thoreau, Lawrence Osborne’s new novel, set on the Greek island of Hydra, echoes the Odyssey, Inara Verzemnieks returns to her grandmother’s village in Latvia, and Rebecca Stott writes of growing up in a cult.

Edwidge Danticat, The Art of Death

Danticat’s memoir Brother, I’m Dying won the 2007 National Book Critics Circle award in autobiography; her novel The Dew Breaker was a 2004 NBCC fiction finalist. Her new book, an addition to Graywolf Press’s series on the craft of writing, interweaves her personal story of her mother’s death from cancer with a thorough and insightful reading of literature on death and dying.

“This book is a kind of prayer for her mother—an act of mourning and remembrance, a purposeful act of grieving,” writes Michiko Kakutani (New York Times). “It’s also a book about how Danticat and other writers have tried to come to terms with the fact of death.”

“Danticat’s is a memoir written in a manner akin to the circular, overlapping and overwhelming processes of grief and mourning,” notes Leah Mirakhor (Los Angeles Times); “she layers her story with other poems, memoirs, novels and essays about death, scaling the personal to wider-ranging political and ecological catastrophes.

The Art of Death is not a novel, points out Maria Murriel (PRI’s The World), “but a book on the craft of writing—specifically about death. The book is a rich exploration of how we understand death—‘one of life’s greatest mysteries’—written in Danticat’s curious, enchanting prose.”

Laura Dassow Walls, Henry David Thoreau: A Life

This 640-page new biography of Thoreau—the first in some 50 years—arrives at a timely moment to mark the two hundredth anniversary of his birth. Critics praise its author for the many new perspectives she offers on the man we thought we knew.

Fen Montaigne (New York Times Book Review) writes, “Laura Dassow Walls’s exuberant biography leaves the reader in no doubt how Thoreau might react to the current administration in Washington, filled as it is with people who deny the established physical science of global warming. Thoreau would pick up his pen to skewer them mercilessly, and—practicing what he preached in his essay ‘Civil Disobedience’—would probably take to the streets in protest.”

At the core of Walls’s book, writes Daegan Miller (Los Angeles Review of Books), “is the stunningly perceptive, deceptively simple insight that ‘[Thoreau’s] social activism and his defense of nature sprang from the same roots: he found society in nature, and nature he found everywhere, including the town center and the human heart.’ Walden and ‘Civil Disobedience,’ in Walls’s view, are of a piece, and Thoreau’s entire life, she contends, was spent in search of whatever it is that connects nature to society, the wild to the domestic, in one ‘community of life.’”

Colin Fleming (San Francisco Chronicle) concludes:

Pleasing to me was to see Cape Cod—Thoreau’s tome about that beguiling, bewitching peninsula, a briny world unto itself—get the plaudits it deserves. Walls rightly calls it ‘Walden’s dark twin,’ with its ‘rough chaos of the liminal zone,’ and the stylized—but still natural—metaphor of the lighthouse keeper making sure that his domicile remains a temple of light rather than darkness. . . .

This is Thoreau’s best writing, his most sonorously poetic, a mellifluous foghorn sounding for you, and your attention, in the deepest lapis lazuli of the night. As Walls writes, Thoreau relished visceral joy—the dance of nature, the reverberation of unadulterated, uncapped feeling—”making this book of darkness blaze with life.” The same phrase could double as an encapsulation for his life, and now this biography, a rectangle of radiance in your hands, with its own glow.

Lawrence Osborne, Beautiful Animals

Osborne’s latest novel involves a Syrian refugee and two young women visiting the Greek island of Hydra. Homer is an inspiration. “The Odyssey is a great poem to refugee-dom,” Osborne tells NPR’s Ari Shapiro. “Odysseus is not entirely a refugee . . . he’s somebody who’s blown off course. The entire book is an exploration of that theme.” I call it “a masterful and sophisticated psychological thriller that explores moral ambiguity from multiple perspectives” in my BBC Culture column.

“In the age of GoFundMe, the act of giving can feel vexingly weightless,” writes Katie Kitamura (New York Times Book Review). “This relationship between ease and charity is the starting point of . . . Beautiful Animals. Of the central character, an entitled young Englishwoman named Naomi, her father observes: ‘She wanted to be a Samaritan: the easiest job in the world, and perfect for the useless European middle classes.’”

“Let’s not mince words,” writes Lionel Shriver (Washington Post). “This is a great book. Truly difficult to put down, the novel exerts a sickening pull. Its climax and resolution will not disappoint. The social perspective is sophisticated, smart and uncomfortable, and the story is cracking.”

Inara Verzemnieks, Among the Living and the Dead

A child of divorce, raised by her paternal grandmother, returns to Latvia five years after her beloved Livija dies, to discover “what history meant in flesh and blood.”

Rebekah Denn (Christian Science Monitor) writes, “In her elegiac new book, [Verzemnieks] describes how she hoped the faraway travels would restore her grandmother to her ‘in the old stories’ that still existed there. In the region of Latvia where my grandmother was raised, there are people who believe even to this day that the right words spoken in the right combination are a way of resurrecting what has been lost . . . Ultimately, what she found was even broader: the meaning of home, the power of stories, and the different ways survivors and their memories move forward.”

Angela Ajayi (Minneapolis Star-Tribune) concludes:

Verzemnieks, a former journalist, is a gracious writer, inviting the readers on her journey into the past. Yet she does so with few guideposts along the way—the book lacks a table of contents and photographs, and its chapters have no titles, just Roman numerals, stark elements of the past. This gives the memoir’s progression, as it moves between present and past, an inscrutable feel, for better or worse. However, armed with her wealth of knowledge in Latvian history and myths, and her masterful and lush observations, Verzemnieks remains an able guide, earning our undivided attention and admiration.

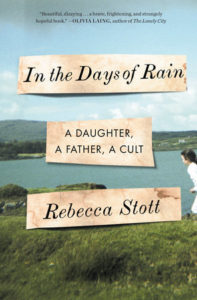

Rebecca Stott, In the Days of Rain: A Father, A Daughter, A Cult

Stott’s memoir explores the Brethren, the cult she was born into in England. “I was full of rage,” she tells NPR’s A Martinez. “I remember I couldn’t show it. I was very good at not showing it because as a Brethren girl, you know, we had to keep our heads covered, we had to grow our hair long, we weren’t allowed to wear trousers. We had to be subject; we had to be silent; women weren’t allowed to speak in meeting. You know, it was extremely conservative in terms of its gender roles. So as a Brethren girl I had to be quiet and good.”

Lara Feigel (Financial Times) writes, “In the Days of Rain interweaves Stott’s personal story with the wider history of the Brethren. As a memoir, it is dramatic, because it leaves the reader wondering anxiously when and how her family will escape. It is also very moving in its portrayal of ambivalent family love. Stott’s father—who seems to have preached for a religion he had no belief in because he enjoyed the thespian pleasures of the pulpit—is a man who was clearly difficult to respect. He ended up in prison because he had embezzled money from the family store to fund his gambling habit. Yet she renders him lovable; his passion and frequently maddening optimism are made enticing on the page. And through their dual stories, she reveals the potency of literature for those who most need it.”

“Her upbringing was unique and fascinating, just like her recollections and reflections are,” notes Stephanie Topacio Long (Bustle).

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.