5 Books Making News this Week: Power, Prequels, and Pulitzer Winners

Ta-Nehisi Coates, Adam Gopnik, Jennifer Egan, and More

The mysterious Nobel Prize in Literature process is unfolding, with the winner to be announced Thursday, October 5 at 7 a.m. EST. U.K. odds-makers, including Ladbrokes, are making a racket, giving advantages to Ngugi Wa Thiong’o, Haruki Murakami, and Margaret Atwood. Your pick?

The six books on the Goldsmiths Prize shortlist “offer resistance to the received idea of how a novel should be written,” writes Dr. Naomi Wood, the chair of judges. “Variously, they break the rules on continuity, time, character arcs, perspective, voice, typographical conventions and structure. As such, there is a wildness to all of our chosen books that provokes in the reader a joyful inquiry about just what a novel might be there to do.” Fitting her description: Nicola Barker’s H(a)ppy, Sara Baume’s A Line Made by Walking, Kevin Davey’s Playing Possum, Jon McGregor’s Reservoir 13, Gwendoline Riley’s First Love, and Will Self’s Phone.

Pulitzer prize winners in fiction Jennifer Egan and Jeffrey Eugenides are back, she with a noirish historic novel, he with a first story collection. National Book Award nonfiction winner Ta-Nehisi Coates gives us a personal and political update, Robin Sloan’s new novel is “delicious fun,” and Adam Gopnik’s latest memoir is a love letter to “a vanished Soho.”

Jennifer Egan, Manhattan Beach

Egan follows up her Pulitzer Prize winner, A Visit from the Goon Squad, with a noir-tinged historic novel. “Realistically detailed, poetically charged, and utterly satisfying: apparently there’s nothing Egan can’t do,” notes Kirkus in a starred review. Manhattan Beach is on the longlist for the National Book Award.

Maureen Corrigan (NPR) writes:

Like every good historical novel I’ve ever read, the storyline of this one is as hokey as hell and completely transporting. Manhattan Beach is ambitiously and deliciously plot-driven, and it boldly helps itself to a wide library of earlier New York stories: There are echoes here of Betty Smith’s A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, the Damon Runyon tales that would became Guys and Dolls and Joseph Mitchell’s briny descriptions from The Bottom of The Harbor.

“One definition of a great novel, William Styron said, is that it should ‘leave you with many experiences, and slightly exhausted at the end. You live several lives while reading it,’” writes Dwight Garner (New York Times). “Jennifer Egan’s immensely satisfying fifth novel, Manhattan Beach… has a good deal of that kind of life-swamping and life-supplementing effect.”

Katherine A. Powers (Newsday) concludes:

Egan’s extraordinary virtuosity of description and power of evoking a historical milieu are on display throughout Manhattan Beach, which is alive with fully realized, brilliantly rendered characters; even minor players are picked out in unforgettable detail. . . . Alight with . . . moments of black comedy, this truly fine novel, so rich in period and emotional atmosphere and so cunningly plotted, is a joy (and a terror)—one of the standouts of the year.

Jeffrey Eugenides, Fresh Complaint

Pulitzer winning novelist Eugenides publishes his first collection, ten stories written over the past two decades. “In some ways, it’s harder to write a short story than a novel,” Eugenides tells The Associated Press’s Hillel Italie in a recent email. “There’s no room for elaboration or expansion, both of which come naturally to the novelist. In creative writing courses, of course, we start students off writing short stories because they’re more manageable. But it’s like asking someone to pilot a jet on his first flying lesson.”

Lisa Zeidner (Washington Post) notes, “Eugenides excels at penetrating—and gently mocking—the insider lingo of academics. He can make a realistic setting seem deliciously weird, and the highlights in these stories often feature simultaneously funny and plaintive images that encourage our appreciation for ‘the pleasant absurdity of America.’”

Zack Ruskin (SF Weekly) writes, “After penning remarkably complex and emotionally astute novels like The Virgin Suicides and Middlesex, Eugenides now performs his mastery on slimmer tales that center on the personal as the profound. From the story of a traveler eager for enlightenment to the transformation of a failed poet who becomes an embezzler, Fresh Complaint is a welcome addition to Eugenides’ extraordinary personal canon.”

Ben East (The Guardian) concludes:

. . . there’s genuine sadness, also explored in the book’s opening tale of a lonely 88-year-old woman sliding into dementia and taken out of her care home by a well-meaning younger woman (divorced, naturally) on a Thelma & Louise-style road trip.

The story ends—and the overall impression of Eugenides the short story writer is that he’s a fine exponent of the satisfying denouement—with the heartbreaking “Keep going. Maybe she’d meet someone out there, maybe she wouldn’t. A friend.” Fresh Complaint is a bit like that—fleeting visits from characters with whom you’d like to spend a little time. But not too much.

Ta-Nehisi Coates, We Were Eight Years in Power

Eight essays written mostly during the Obama presidency for The Atlantic, where he is national correspondent, each introduced by a personal mini-essay, update the work of the National Book Award winner for nonfiction.

“A new book from Coates is not merely a literary event,” notes Jennifer Senior (New York Times). “It’s a launch from Cape Canaveral. There’s a lot of awe, heat, resistance. The simplest way to describe We Were Eight Years in Power is as a selection of Coates’s most influential pieces from The Atlantic, organized chronologically. The book is actually far more than that, but for now let’s stick with those pieces, which have established Coates as the pre-eminent black public intellectual of his generation.”

“Across his oeuvre, Coates’ prose style and literary prowess are hip-hop sharpened: he believes in the art of dexterous reference, potent, lyrical critique and political storytelling,” notes Walton Muyumba (Los Angeles Times). And he adds:

. . . Coates hasn’t been and isn’t alone in interrogating the American milieu shrewdly, passionately. To my mind, Coates is part of a necessary cipher of extremely gifted freestylers—say, Isabel Wilkerson, Carol Anderson, Claudia Rankine, Terrance Hayes, Kiese Laymon, Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah, Junot Díaz, Jaquira Díaz, Jelani Cobb—writers who break away from the dream, rhyming improvised verses over the Baldwinian beat: “Our dehumanization of the Negro then is indivisible from our dehumanization of ourselves: the loss of our own identity is the price we pay for our annulment of his.”

Carlos Lozada (Washington Post) concludes:

I would have continued reading Coates during a Hillary Clinton administration, hoping in particular that he’d finally write the great Civil War history already scattered throughout his work. Yet reading him now feels more urgent, with the bar set higher. Early in this book, Coates writes that having the Obamas in the White House “opened a market” for him. Trump opens one, too.

Robin Sloan, Sourdough

Sloan’s second novel focuses on the richly rewarding food culture of the San Francisco Bay Area. Why? “About the same time that I was publishing Penumbra, I got a book called Tartine Bread, kind of a well-known baking book that insists that you’ve got to do it with sourdough. They have like no patience for dry, you know, store-bought yeast. And for me, learning what the starter was and how it behaved was a total revelation,” Sloan tells The Verge’s Chaim Gartenberg.

Jason Sheehan (NPR) is enthusiastic:

Robin Sloan’s new novel, Sourdough, is exactly like his first book, Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore, except that it’s not about books (exactly), but is absolutely about San Francisco, geeks, nerds, coders, secret societies, bizarrely low-impact conspiracies that solely concern single-noun obsessives (food, in this case, rather than books), and also robots. And books, too, actually, now that I think about it.

It is a beautiful, small, sweet, quiet book. It knows as much about the strange extremes of food as Mr. Penumbra did about the dark latitudes of the book community.

Elizabeth Hand (Washington Post) describes Sourdough as “delicious fun.” She concludes, “My only mild disappointment was that I couldn’t eat my copy.”

“The novel defies clear-cut analysis,” writes Chelsea Leu (San Francisco Chronicle). “It pushes us to do something simpler, to wonder at the weird beauty, set down in Sloan’s matter-of-fact prose, of life — or at least marvel at the strange sights and tastes of a familiar world embellished by a particularly inventive mind.”

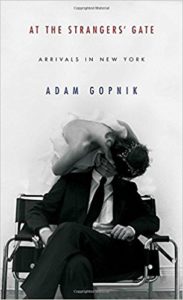

Adam Gopnik, At the Strangers’ Gate

The New Yorker staffer Gopnik writes a prequel to his memoirs Paris to the Moon and Through the Children’s Gate. Response is mixed.

Steve Donoghue (Christian Science Monitor) likens At the Strangers’ Gate to Anatole Broyard’s classic 1993 memoir Kafka was the Rage. “But where Rage was a love-letter to a vanished Greenwich Village, Gopnik’s book is a love letter to a vanished SoHo, where he and his wife miraculously find a charming little loft that doesn’t cost Fort Knox. From the vantage point of their rent stabilized home, they’re able to watch the neighborhood blossom and change . . . ”

Gopnik’s book is “at once self-deprecating and self-celebrating,” writes Heller McAlpin (Washington Post). “Gopnik doesn’t always show himself in the most flattering light. He acknowledges his driving ambition even as he describes relationships with ‘Dick’ Avedon, Robert Hughes and other steppingstone mentors that carry whiffs of sycophancy. In his determination to capture the zeitgeist of the 1980s in art, food, publishing and fashion, his smart observations are sometimes undercut by pontifications: ‘Art traps time. It just does.’”

Vivian Gornick (New York Times Book Review) is not a fan. She concludes:

What we have here is the story of a pair of privileged young adults who suffer neither intellectual disappointment nor spiritual disillusion nor emotional setbacks: everything that is required for a person to mature. As they are at the beginning, so Adam and Martha are at the end. Consequently, what is missing from At the Strangers’ Gate is a sense of progress toward self-discovery: the very essence of any memoir that hopes to achieve lasting value.

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.