5 Books Making News This Week: Politics and Poets

Linda Gordon, Victor Sebestyen, James Blunk, and More

The 2017 Langston Hughes Medallion goes to to Zadie Smith. The Crime Writers Association Diamond Dagger Award goes to Ann Cleeves. (The judges cite the books on which the TV series Vera and Shetland are based, her 30 “hugely enjoyable crime novels,” her role as a “passionate and effective advocate for libraries”, and “her generosity towards fellow crime writers as well as readers.”) The finalists for the ALA’s Carnegie Medals are Jennifer Egan’s Manhattan Beach, George Saunders’ Lincoln in the Bardo, and Jesmyn Ward’s Sing, Unburied, Sing (fiction) and Sherman Alexie’s You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me, Daniel Ellsberg’s The Doomsday Machine, and David Grann’s Killers of the Flower Moon (nonfiction).

James McBride’s new collection is “a pinball machine zinging,” historian Linda Gordon describes the KKK resurgence in the 1920s, the first authorized biography of Oriana Fallaci, who made a “career of battering politicians, celebrities and dictators” is here, Victor Sebestyen’s new book on Lenin is first-rate history that “reads like a thriller,” and a life of James Wright is a “sad, even tragic story.”

James McBride, Five-Carat Soul

Winner of the National Book Award for his novel The Good Lord Bird is back with a finely tuned story collection. “These stories give me the room to breathe,” McBride tells the Washington Post’s Carole Burns. “Fiction offers some relief from the drudgery of sitting on the third rail of race, where most of us sit or avoid. Fiction allows us to dream. Without dreams what do you have? Fiction gives you real hope.”

Tayari Jones (New York Times Book Review) calls McBride’s new collection “a pinball machine zinging with sharp dialogue, breathtaking plot twists and naughty humor,” noting, “At the same time McBride also plumbs the vast emotional terrain underneath performances of masculinity, questioning what it is to be a man rather than a woman rather than a boy rather than a beast.”

“McBride lets his sense of whimsy run wild in this collection,” writes Tyron Beason (Seattle Times). “The closing entry, ‘Mr. P and the Wind,’ about an enchanted zoo where the animals can communicate with each other through their thoughts and read the mouths of humans, who they call ‘Smellies,’ is a loopy and macabre bedtime story for kids at heart. McBride is at his best in this off-kilter mode.”

Michael Schaub (NPR) concludes:

The stories in Five-Carat Soul vary widely in style and setting, but they’re all linked by the author’s compassionate sensibilities. The characters in this book—human and otherwise—feel real and beautifully drawn, and their stories are bound to stay with readers for a very long time.

Linda Gordon, The Second Coming of the KKK

In her timely new book, the NYU historian focuses on a little-known aspect of twentieth-century American political life.

Deborah Douglas (Vice) writes, “Second Coming of the KKK illustrates how a ne’er do well Atlanta physician dusted off racist remnants of the post–Civil War Klan aimed at maintaining white supremacy in civic and social life in the South. With the help of a couple of savvy public relations pros, Klan membership spread like wildfire, enveloping Northerners and Westerners in love with the idea of defining themselves by what they were not, including being black, Jewish, Catholic, or recent immigrants.”

Todd Moye (Texas Observer) writes:

The Second KKK, Gordon argues, influenced the national conversation in ways that still resonate. “The Klannish spirit—fearful, angry, gullible to falsehoods, in thrall to demagogic leaders and abusive language, hostile to science and intellectuals, committed to the dream that everyone can be a success in business if they only try—lives on,” she concludes.

Does it ever, and Gordon is not shy about connecting the dots.

Gordon is a “thorough and perceptive historian, and she’s careful to keep most of her opinions to herself,” writes Randy Dotinga (Christian Science Monitor). “She is willing, however, to link the KKK of the 1920s to today’s American politics, especially the nationalist movement. But there’s more to The Second Coming than grim déjà vu. There are lessons, too.”

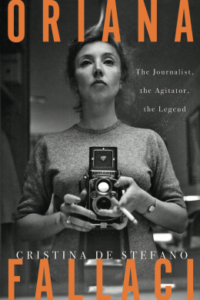

Cristina de Stefano, Oriana Fallaci

Intimate glimpses drawn from her personal archives show the family background and vulnerabilities of the fierce and charismatic journalist.

“It’s the first authorized biography we have of Fallaci, with access to new personal records, and welcome for that reason,” writes Dwight Garner (New York Times). “It is not particularly well-written or thoughtful but it gets her story onto the page and, thanks to its subject, is never dull.”

“Fallaci had made a career of battering politicians, celebrities and dicatotors,” notes Michael Moynihan (Wall Street Journal), “reminding us of what Henry Kissinger once confessed was “the single most disastrous conversation [he] ever had with any member of the press.”

James Marcus (Los Angeles Times) brings up another interview.

While she continued to function as a war correspondent, Fallaci found another way to vent her rage at the abuse of power: the interview. There is a wonderful irony here. Having cut her teeth interrogating the merely famous, she upgraded to the high, the mighty, the Shakespearean movers-and-shakers. They were mostly men, and they were mostly intimidated by this wily, theatrical, fearless woman with a microphone . . . Talking with the Ayatollah Khomeini in 1979, she responded to a jeering comment about her respectability by ripping off her chador: “I’m going to take off this stupid, medieval rag right now. There. Done.” (Khomeini fled the room at once.)

Victor Sebestyen, Lenin

A new look at the life of Lenin through the lens of his relationships, timed to coincide with the centennial of the Bolshevik revolution.

Josef Joffe (New York Times Book Review) is enthusiastic:

Can first-rate history read like a thriller? . . . Victor Sebestyen has pulled off this rarest of feats—down to the last of its 569 pages. How did he do it? Start with a Russian version of “House of Cards” and behold Vladimir Ilyich Lenin pre-empt Frank Underwood’s cynicism and murderous ambition by 100 years. Add meticulous research by digging into Soviet archives, including those locked away until recently. Plow through 9.5 million words of Lenin’s “Collected Works.” Finally, apply a scriptwriter’s knack for drama and suspense that needs no ludicrous cliffhangers to enthrall history buffs and professionals alike.

“The Bolshevik coup disproves the Marxist idea that social and economic forces rule history, as Victor Sebestyen comments in his engaging, highly readable new life of Lenin,” writes David Mikics (Tablet). “Without Lenin’s shrewd tactics, his movement would have been just as feeble as the rest of Russia’s political parties. The Bolsheviks never enjoyed wide support, but they had Lenin’s Machiavellian individual brilliance. Lenin’s tactics were masterful: Encourage schisms; castigate your opponents; make no compromises; refuse all coalitions. He held fast to the key plank that the Mensheviks foolishly rejected: He would end the war immediately upon taking power.”

Sebestyen “brings the man’s complexities to life . . . balancing personality with politics in succinct and readable prose,” writes David Reynolds (New Statesman). “Like other biographers, Sebestyen roots young Vladimir’s revolutionary turn in the double trauma in 1886-87 of his father’s sudden death and his elder brother’s execution for plotting to kill the tsar. From now on Lenin’s one-track, control-freak mind was fixed on the goal of a Russian revolution, in defiance of Karl Marx’s insistence that this would be impossible until feudal peasant Russia had first become a bourgeois society.”

Jonathan Blunk, James Wright: A Life in Poetry

PW’s reviewer calls this new biography of the Pulitzer Prize winning poet “unarguably the definitive work on Wright,” and adds, “this biography contains perhaps more than a simple admirer of his work needs to know.”

David Yezzi (Wall Street Journal) kicks off:

A pure product of the American Midwest, the poet James Wright (1927-80) wanted desperately to escape his hometown of Martins Ferry, Ohio, but his Rust Belt upbringing just wouldn’t leave him alone. Even after moving to New York and garnering a Pulitzer Prize for his Collected Poems (1971), Wright still feared that the place might somehow reclaim him. As Jonathan Blunk recounts in his fluent biography, it was in Martins Ferry, in the wake of the Great Depression, that work at the nearby Hazel-Atlas Glass Co. circumscribed his father’s life.

“Jonathan Blunk, the authorized biographer, shows considerable empathy for his subject, and his sensitivity to the poetry shines through this long and detailed work,” writes Mark Gustafson (Minneapolis Star-Tribune). “But be forewarned: It is a sad, even tragic, story.”

Troy Jollimore (Washington Post) concludes:

Wright endured his share of difficulties: a bad first marriage ending in a financially and spiritually devastating divorce; his enforced separation from his two sons (one of them, Franz Wright, went on to win the Pulitzer for his own poetry); the challenge of securing reliable academic employment; and, perhaps most damagingly, his lifelong struggle with alcoholism, which led him in his later years to Alcoholics Anonymous . . .

These hardships lend some narrative drama to Blunk’s biography, an intermittently entertaining read that will serve as a useful source for readers interested in the poet’s life. Ultimately, however, James Wright comes across as unsatisfyingly exterior. Wright’s dramas played out within his mind and on the pages he left for us. It is there—in his poems and wonderful letters—that we find his humor, his tenderness, his insecurity, his unique and unforgettable voice. In the end, we must turn to Wright’s own words to get a true sense of the man, which is just the way he would have wanted it.