5 Books Making News This Week: Misfits, Survivors, and Revolutionaries

Lidia Yuknavitch, Richard Lloyd Parry, and Janet Fitch

One highlight of the Texas Book Festival in Austin this past weekend is the announcement of the Kirkus Prize winners, each awarded $50,000. Lesley Nneka Arimah wins the fiction prize for What It Means When a Man Falls from the Sky: Stories, which the judges laud as “a kaleidoscopic and emotionally powerful collection that displays remarkable range, shifting from a dystopian exploration of a futuristic society to the interplay between mothers and daughters and to the legacy of the violent political struggles of Nigeria’s past.” The nonfiction prize goes to Jack E. Davis’ The Gulf: The Making of an American Sea (“a groundbreaking history of the sea illuminating the complex forces ravaging our environment”), and the Young Readers’ Literature prize to Cherie Dimaline’s The Marrow Thieves (a “poetic and lyrical novel . . . in which, she presents the links between our past and our future in a world where dreams are harvested by those who continue to oppress the Indigenous peoples of North America”).

Also in Austin, Dan Rather—journalist, author and Wharton County native—is honored with the Texas Writer Award, as he launches his new book, What Unites Us: Reflections on Patriotism. Lidia Yutnavitch expands her TED talk, through a new book and a #MisfitManifesto Twitter campaign, Janet Fitch’s new novel is a coming-of-age story coinciding with the Bolshevik Revolution, John Banville offers a sequel to Portrait of a Lady, Richard Lloyd Parry assesses the aftermath of the 2011 Japanese tsunami, and Adam Federman writes a life of Patience Gray, the idiosyncratic author of Honey from a Weed.

Lidia Yuknavitch, The Misfit’s Manifesto

A 2016 TED talk that found some 2 million viewers leads to a nonfiction book, launched at Powell’s, propelled by excerpts in Oprah and the Literary Hub and a #MisfitManifesto Twitter Campaign that draws hundreds, including Elissa Schappell (“When I was a girl my family visited Scotland, I smuggled water I took from Loch Ness back home for my witchcraft”), David L. Ulin (“The high school writing teacher who flunked me and told me to ‘disavow myself’ of the notion I had talent”), and Matthew Zapruder, who tweets “dear @LidiaYuknavitch here is one of so many moments I discovered I did not and couldn’t belong” and links to a new poem. Yuknavitch rocks the zeitgeist.

“This small book roars in Yuknavitch’s big voice, arguing in favor of compassion, justice, and love for the misfits among us who choose (or are forced) to take the long view visible only from society’s margins,” writes Meredith Maran (Christian Science Monitor).

Matthew Korfhage (Willamette Week) notes, “Though Manifesto is occasionally pocked by academic bromides like ‘addiction may be the logic of late capitalism,’ the idea that animates the book is that the misfit may be more essential to life than the hero. Yuknavitch quotes the poem at the base of the statue of liberty…In many ways the misfit’s journey she describes is a story that defines our country, the waves of refugees who ‘started out in hell’ only to arrive at a place that didn’t understand them. The hope of the misfit is the hope of America, and it’s not a hero’s triumph. It’s the refusal to surrender, the unbending will to live that defines life itself.”

Janet Fitch, The Revolution of Marina M.

Dostoyevsky established for Fitch what a novel could and should be—“big, intense, brimming with high drama and unforgettable characters,” she tells me. She majored in Russian history in college; decades later, while visiting St. Petersburg researching this book, she was invited to lecture at the Dostoevsky Literary-Memorial Museum—in the very apartment where the master composed some of his greatest works. Her 800-page novel brims, indeed.

“The novel is both story and history, which prove inseparable, as the young life of our heroine, Marina Makarova, is upended first by the Russian Revolution and later by the Civil War,” writes Ani Kokobobo (Los Angeles Review of Books). “But despite the book’s size and the headiness of the material it tackles, Marina’s unlikely Bildungsroman—her growth, her loves, her dreadful losses and disappointments, but, above all, her enduring hope and determination to survive, against all odds—proves so gripping that it’s hard to put the book down.”

Simon Sebag Monfefiore (New York Times Book Review) points out the factual framework of Fitch’s book:

Like Marina, the real women who became revolutionaries often hailed from noble families, perhaps the most famous of them being the Bolshevik Alexandra Kollontai, the Communist daughter of a czarist general. Women in this milieu endured prison sentences and Siberian exile but also enjoyed love affairs with male revolutionaries (some of whom they married).

Kollontai especially was a trailblazer who, in tracts such as her 1921 essay “Theses on Communist Morality in the Sphere of Marital Relations,” advocated free love in powerful, forward-thinking axioms: “Sexuality is a human instinct as natural as hunger or thirst.” She believed that marriage was an oppressive bourgeois concept based on the presumption of female dependence on men, a notion that would be rendered obsolete under socialism, when both sexes would depend only on society.

“The Revolution of Marina M. is an often exasperating, strange story of a spoiled, entitled aristocratic girl coming of age during the Russian Revolution,” writes Trine Tsouderos (Chicago Tribune). “And yet, despite its narcissistic heroine and its meandering story, Janet Fitch’s novel shimmers with vital energy.”

John Banville, Mrs. Osmond

Taking on a sequel to Henry James’s Portrait of a Lady is risky business, even for a Man Booker award winner, as evidenced by the mixed tone of the reviews. Banville acknowledged that the project was “like feeding on the corpse of a great lion,” and predicted he would be called “arrogant, foolhardy and stupid.” Critics were kinder than that.

Edmund White (The Guardian) writes:

Mrs. Osmond is both a remarkable novel in its own right and a superb pastiche. But I found irritating the very mannerisms that try my patience in James; I remember once reading in The Golden Bowl, “Her thick hair was what could vulgarly be called brown,” and throwing the book against the wall (why should the colour brown be “vulgar”?). When his enigmas are all lined up, no one is more gripping than James. Still, I prefer Banville’s own nuanced, exciting voice, as in Ancient Light or The Sea.

Heller McAlpin (Los Angeles Times) calls the book a “risky homage and sequel” that “feels more repetitive than fresh, particularly for those familiar with the original.” She adds, “While Mrs. Osmond does indeed answer questions that remained at the end of what James called his ‘ado about Isabel Archer,’ Banville, too, has left plenty of windows open to this vivid, strong-willed heroine’s next chapters.”

Christine Smallwood (Harpers) concludes:

The overriding reason Mrs. Osmond fails is that Banville sidesteps the questions that worry the readers of Portrait. The problem of James’s ending is not that we don’t know what Isabel does—it’s that we must answer why. Why is it that she, as James has it, “can’t escape unhappiness”? For what end, or for whom, is she living? What meaning can she wring from her disillusionment? Banville waves a wand and these questions vanish. His is a rescue mission, not a literary one. (You might as well show up in Jude the Obscure and start passing out contraceptives.) He has the sense not to marry Isabel off to someone else, but doesn’t know what to do with her. James gave Isabel’s life an arc and a destiny, however tragic. Banville restores her to the condition in which we first met her: a single, uncommitted heiress who wants to be free. But freedom, as Portrait shows, is hardly an end in itself.

Richard Lloyd Parry, Ghosts of the Tsunami

Parry, was Asia Editor of the Times of London, was working in Tokyo when the disaster struck Japan in 2011, beginning as an earthquake, becoming a tsunami and disaster at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. He spent the next six years covering the story. “The strengths and weaknesses of Japanese society were brought out by the tsunami, not so much in the disaster itself but in the aftermath,” Parry tells Bloomberg’s Nisid Hajari. “These people who were washed up by the wave did form strong bonds, did help one another out, there was heroism, self-sacrifice—and those are things we celebrate. But overall, the pain outweighed the consolation. And sadly, the same thing is true at the national level. I think that the legacy of this disaster is a weaker, less confident, more vulnerable Japan than before.”

Michael Schaub (NPR) appreciates Parry’s perspective:

Parry writes about the survivors with sensitivity and a rare kind of empathy; he resists the urge to distance himself from the pain in an attempt at emotional self-preservation. The result is a book that’s brutally honest, and at times difficult to read. “A tsunami does to human connectedness the same thing that it does to roads, bridges, and homes,” he writes. “And in Okawa, and everywhere in the tsunami zone, people fell to quarreling and reproaches, and felt the bitterness of injustice and envy and fell out of love.” Ghosts of the Tsunami is a brilliant chronicle of one of the modern world’s worst disasters, but it’s also a necessary act of witness.

One of the most startling moments of the book, Lisa Levy (New Republic) writes, “is a description of the tsunami by a government functionary named Teruo Konno. Konno describes his ordeal in terrifying detail. As the building he worked in was hit by the tsunami, he was surrounded by swirling water. ‘I never heard anything like it,’ Konno says. ‘It was partly the rushing of the water, but also the sound of timber, twisting and tearing.’ Lloyd Parry explains, ‘In the space of five minutes, the entire community of 80 houses had been physically uprooted and thrust, bobbing, against the barrier of the hills.’ It is in these accounts that we finally can start to comprehend what the experience of the tsunami was like. It’s hard to think about the waves crashing on the beach in quite the same way, so powerful is Ghosts of the Tsunami. Lloyd Parry’s account is truly haunting, and remains etched in the brain and the heart long after the book is over.”

“Grief differs,” concludes Leaf Arbuthnot (Times of London). “It divides. Some survivors were left with enough to rebuild. Others lost too much. Of the children who survived the Okawa primary school disaster, Tetsuya Tadano was the only one to speak openly of his experiences. His tale, in a way, is encouraging—he became captain of his high-school judo team. But in his schoolbag was a picture of his lost schoolmates. ‘If I carry it in my bag, I feel as if they are having lessons with me,’ he says.”

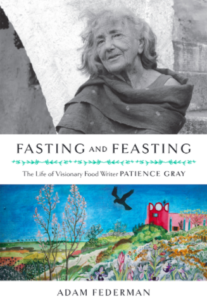

Adam Federman, Fasting and Feasting

Federman launches the first biography of pioneering foodie Patience Gray, who wrote, “Pounding fragrant things—particularly garlic, basil, parsley—is a tremendous antidote to depression.”

Laura Shapiro (New York Times Book Review) notes, “Gray was an extraordinary creature, quite unlike any of the other female icons who dominate postwar culinary history. Maybe that’s why culinary history hasn’t often treated her as one of its own. Books about Elizabeth David, M.F.K. Fisher, Julia Child and Alice Waters are plentiful by now, . . . but Fasting and Feasting is the first about Gray, though she became a cult figure with the publication of Honey From a Weed in 1986.”

Nancy Matsumoto (NPR) writes, “What emerges from his book is a portrait of a strong-willed, intellectually curious and intelligent woman who chafed under the restrictions of both bourgeois urban life and parenthood. She could be both competitive and cutting to those she viewed as rivals, yet also a fiercely loyal friend to many and a tireless correspondent, practicing a form of epistolary art that combined drawings and multi-colored typewritten sentences and expressed her love of graphic design.”

“The book is a satisfying portrait of an uncategorical woman,” writes Julia Berick (Paris Review). “The biography begins with a tension that suffuses the entire book. Gray ‘liked to say that life began at Spigolizzi,’ where she moved with her lover at the age of 52. But Federman carefully (though not tediously) notes all the years prior as well.”

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.