5 Books Making News This Week: Magic, Memoirs, and Conspiracies

Alice Hoffman, Jeannie Vanasco, The Obama Inheritance, and More

The week has showered honors and bucks on many writers. Novelists Viet Thanh Nguyen and Jesmyn Ward earn MacArthur Grants, ($625,000 over five years, the gift of “time and freedom,” as Ward put it to the AP’s Janet McConnaughey). Whiting Creative Nonfiction Grants for works in progress, which clock in at $40,000, go to eight writers, including Phil Gourevich, Meghan O’Rourke, George Packer, and Julie Phillips. Poets and Writers honors “Five Over 50” writers Jimin Han, Laura Hulthen Thomas, Karen E. Osborne, Tina Carlson and Peg Alford Pursell.

Alice Hoffman’s magical prequel draws glowing reviews, as do complicated memoirs by Jeannie Vanasco and Xiaolu Guo. Liz Mundy uncovers the invisible world of Code Girls, and Gary Phillips asks 15 writers to write about The Obama Inheritance.

Alice Hoffman, The Rules of Magic

The prequel to Hoffman’s 1995 best seller Practical Magic reaches back to 1680. “I didn’t really realize that in colonial America, and in colonial New York, magic was rampant,” Hoffman tells NPR’s Lulu Garcia-Navarro. “There was so much magic going on in early New York, and you kind of never hear that. It’s always the secret history, because it’s the history of women. It isn’t written down—it’s just told. It’s an oral tradition.”

“The magic in these endearing witches is in their everydayness,” writes Patty Rhule (USA Today). “They cope with high-school mean girls, apply to college, play music and oh yes, can hear each other’s thoughts, move furniture with their minds and are unable to sink in water.”

The story “unfolds in romantic and magical ways against the backdrop of 1960s, with the Stonewall riot, LSD in Central Park, Bob Dylan and Vietnam all making appearances,” concludes Marion Winik (Newsday). “Hoffman will keep you guessing until the very end of the book how the Practical Magic generation fits in, a clever, heartbreaking finale.”

Jeannie Vanasco, The Glass Eye: A Memoir

Vanasco’s memoir begins with a promise to her dying father, and traces a decade of obsessions with him and the death of a half sister who shared her name.

Amy Jo Burns (Ploughshares) is enthusiastic:

Is grief an illness, a part of illness, or a separate entity unto itself? Essayist and poet Jeannie Vanasco expertly explores the trinity between grief, psychosis, and creativity in a taut memoir about her beloved father and all that arose in his absence. This book has a blazing lyricism to it, one that’s bound to be a trademark of Vanasco’s limber mind.

“Jeannie Vanasco explores [the] link between mental illness and the compulsion to write in her new memoir,” notes Andrew Schenker (Los Angeles Review of Books). “She traces the process that led her to undertake the book, the fulfillment of a promise she made to her dad shortly before he died when she was 18. Promise or no promise, though, we soon come to understand that she could not not write this book, since she’s long been obsessed with the memory of her father and since, she tells us early on, she’s been making various attempts at telling her father’s story for over a decade, ‘poems, essays, short stories, a novel, several versions of a memoir—all titled The Glass Eye.’”

Isabella Biedenharn (Entertainment Weekly) compares The Glass Eye to Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts. “The Glass Eye isn’t a straightforward memoir: Rather, it’s a self-aware chronicle of her struggles as she talks us through her process on the page (‘I worry I’m too easily swayed by the sonic impact of a line’) or researches the sparse facts of her half sister’s death. As the pages fly by, we’re right by Vanasco, breathlessly experiencing her grief, mania, revelations, and—ultimately—her relief.”

Kristin Iverson (Nylon) concludes, “It’s a journey that takes Vanasco into the dark depths of her family history, as well as her own psyche, and it shows in an incredibly intimate methods we use to cope with loss, disappointment, and grief, and how we can try and make our way out of the darkness and into a place of recovery.”

Xiaolu Guo, Nine Continents

A Taoist monk predicted the young Guo would journey far from the village in China where she was born in the 1970s, and indeed she has. Her memoir traces her combination of talent and iron will.

Kirkus Reviews calls the book a “rich and insightful coming-of-age story of not only a woman, but an artist and the country in which she was born.”

“Almost 20 years since she published her first novel in China, Guo lays bare her first 40 years in a single book, and for all her international success in print and celluloid, her life is a raw record of detachment, shame, and suffering,” writes Terry Hong (Christian Science Monitor). “Nine Continents arrives this month in the U.S. as a testimony to resilience and hard-earned peace. Undoubtedly galvanized by the birth of her daughter at 40, Guo admits ‘the time had come to face the past.’”

Pialo Roy (Toronto Star) concludes:

Nine Continents is a compelling and often startling read, written in a direct style with a few moments of sentimentality. Guo intersperses scenes from a Buddhist folk tale throughout the book, providing a dreamy feel to an often hard-edged story. While she does discuss the many influences on her artistic life, Guo does not really reflect on her practice. It feels strange that a prolific novelist and filmmaker would exclude discussing her many works in English and Chinese.

What Guo does detail is the quest for freedom in a changing communist China, the anguished pull of family, and the loneliness of a new immigrant. Ultimately, the memoir is a feminist meditation on the yearning to balance individuality with belonging and find a home.

Liza Mundy, Code Girls

More than 10,000 women worked as code breakers during World War II. Liz Mundy tells their story in a book Kirkus’s starred review calls a “well-researched, compellingly written, crucial addition to the literature of American involvement in World War II.”

Randy Dotinga (Christian Science Monitor) writes, “Mundy learned about the women from a book about a decades-long counterintelligence operation that referred to the surprising number of wartime code breakers who were female schoolteachers. Intrigued, Mundy uncovered a hidden world.”

“In researching this extraordinary book, Mundy perused declassified Army, Navy and NSA archives,” notes Joe Peschel (Houston Chronicle). “And she managed to get some, but not all, material declassified. She also examined private collections and oral histories, and conducted interviews with some of the code girls and their relatives. Mundy’s book is expansive and precise. It’s anecdotal enough to make it an entertaining read for the layperson, and there’s plenty of technical detail to interest the crypto-nerd.”

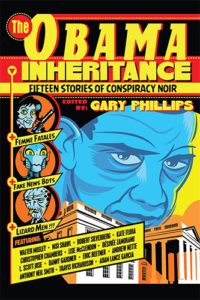

The Obama Inheritance, ed. Gary Phillips

An anthology of 15 themed stories draws attention to conspiracy theories circulating around the Obama presidency.

Maureen Corrigan (NPR) writes, “Phillips, who has written some terrific hard-boiled mysteries himself, invited each of these contributors to chose one Obama conspiracy theory and ‘[r]iff on it, take it apart and turn it on its head, and give the reader a thrill ride of weirdo, noirish, pulpy goodness.’ The overarching aim of all this outlandishness is to entertain, as well as to tuck some social criticism into the formulaic folds of these tales of spooks, spies, private eyes, clones, bots and alien invaders.”

Kirkus Reviews calls the book “a surprising, though sometimes frustrating, collection that uses genre fiction to confront the impact of Obama’s presidency on the white American psyche.”

“The 15 entries in this intriguing theme anthology riff with mixed success on the weird, mostly racist conspiracy theories that followed Barack Obama through his White House years, including those of the phony birth certificate, death panels, and secret lizard people,” notes Publishers Weekly, calling out several stories:

Several of them are truly excellent, notably Travis Richardson’s “I Know They’re in There!,” in which death panel believers take hostages at a hospital, and Walter Mosley’s “A Different Frame of Reference,” in which the only dirt that detectives can dig up on Obama for a white men’s group is that he smokes.