5 Books Making News This Week: Labors, Lawyers, and Lost Ships

Hannah Tinti, Malin Persson Giolito, Paul Watson, and More

Isabel Allende wins the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award for lifetime achievement, with honors also going to Peter Ho Davies’ The Fortunes (fiction), Karan Mahajan’s The Association of Small Bombs (fiction), Margot Lee Shetterly’s Hidden Figures (nonfiction) and Tyehimba Jess’s Olio (poetry). Finalists for the New York Public Library Young Lions Fiction Award are Clare Beams (We Show What We Have Learned), Brit Bennett (The Mothers), Kaitlyn Greenidge (We Love You Charlie Freeman), Nicole Dennis-Benn (Here Comes the Sun) and Karan Mahajan (The Association of Small Bombs). The $10,000 Bancroft Prize, awarded by Columbia University for books about “diplomacy or the history of the Americas,” goes to three books: The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America by Andrés Reséndez; Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy by Heather Ann Thompson, and Remaking the American Patient: How Madison Avenue and Modern Medicine Turned Patients into Consumers by Nancy Tomes. Hannah Tinti writes a dazzling variation on the 12 labors of Hercules, the presenter of BBC’s Museum of Lost Objects offers a first short story collection, a sommelier details her training in Cork Dork, a Pulitzer Prize winning photojournalist tells two tales, about the doomed 1845 Franklin expedition to the Arctic, and how the long-lost ships were found, and the first English translation from a Swedish lawyer turned thriller writer.

Hannah Tinti, The Twelve Lives of Samuel Hawley

Critics rave bout Tinti’s father-daughter novel, inspired by the myth of Hercules.

Lucy Feldman (Time) writes, “Samuel Hawley is a rugged, gun-toting single father (call Brad Pitt’s agent) with 12 bullet scars, inspired by the 12 labors that Hercules performed as penance for murdering his family. ‘There are dark stories behind heroes, terrible things they have to do to accomplish their goals,’ Tinti explains. By that definition, Hawley certainly qualifies as a hero. He blurs the lines between caregiver and criminal, raising his daughter Loo on the run, while keeping secret how her mother died. Half of the chapters follow Loo, telling the story of a girl raised a little bit wild. The rest flash to Hawley’s far darker past, plunging into scenes of crime and revenge.”

“Every other chapter of the novel takes us back to some near-deadly adventure in Hawley’s criminal past that started with robbing gas stations and ended with fencing priceless antiques,” notes Ron Charles (Washington Post). “It’s a breathless relay race of missteps, disasters and murder that stretches for years. It’s also a master class in literary suspense. Hercules himself might feel daunted by the labor of writing tales for 12 bullets, but Tinti is indefatigable. Each one of these stories drops us into a different setting somewhere in the country, establishes a tense situation in progress and then barrels along until slugs start tearing into flesh. Given the repetition, you would think we would come to anticipate Tinti’s methods and grow weary with these near-escapes, but each one is a heart-in-your-throat revelation, a thrilling mix of blood and love . . . And the ingenuity of these tales is matched by a rambunctious range of tones—from macabre comedy to scalding tragedy.”

Dan Cryer (Newsday) compares Tinti to Russell Banks and Richard Russo, in urging us “to be open to the humanity beneath the screw-up, the kernel of goodness beneath the lawbreaker. Her ordinary people just want to be loved.”

Kanishk Tharoor, Swimmer Among the Stars

This first story collection from the presenter of the BBC series Museum of Lost Objects draws in part on his upbringing in Calcutta, New York, and Geneva with his father, Indian statesman Shashi Tharoor. O Magazine calls it “A virtuoso debut collection that is as globalist as it is fabulist.” “If you put a gun to my head and said Faulkner or Hemingway, it would be Faulkner every day,” the author tells Electric Literature’s David Busis.

Swimmer Among the Stars, notes Sabrina Toppa (Mother Jones), “is refreshing for its lack of attachment to national borders. Blending together the futuristic and folkloric with contemporary social and political concerns, Tharoor leads readers from a circus-like ethnography of a single woman speaking an endangered language to an eerie Skype call between a coal mine worker and the foreign photojournalist who splashes his image on a magazine.”

Jason Heller (NPR) writes:

The same way that Swimmer Among the Stars offers a short story nested within a short story, Borges-like, so does another part of the book offer a short story collection nested within a short story collection. “The Mirrors of Iskandar” is a sequence of fourteen brief tales imagined to exist within the framework of the real-life Romance of Alexander, a form of viral fiction written between the 4th and 16th centuries. In explaining this framework, Tharoor’s preface states that “the purpose of the romance was never to tell a straightforward story. Its stories offered variously a vision of ideal kingship and courtly behavior; a cautionary tale about arrogance and ambition; prophetic revelations; a description of fantastical adventures; and a sense of the deep, conflicted past of the world as well as its fundamental impermanence.” Cleverly and with no small amount of chutzpah, Tharoor is telegraphing his own checklist for the stories in Swimmer.

“The dozen or so stories in Tharoor’s collection are mostly gentle, fabulistic concoctions that are easy to embrace,” writes Steve Donoghue (Open Letters Monthly). He finds the collection uneven. “Some of these stories are animated by a wan kind of whimsy that doesn’t always sustain much in the way of energetic reading.” However, he adds, “the main advantage to importing so much whimsy into fiction is to enhance the strangeness of the narrative, and it’s to Tharoor’s credit that he manages to do this so effectively even when writing stories set in the near-present; the image of history ripples when this author runs his fingers through it, and when the device is particularly successful, it hints at some future epic that might speak volumes to an age set adrift from the past. And Tharoor’s instinct for when to pause and simply appreciate the strangeness is his strongest gift as a writer.”

Bianca Bosker, Cork Dork

Bosker quit her job as a Huffington Post editor and started over again as a “cellar rat,” training to become a sommelier. Her oenophilic journey is a hit.

“‘Cork dork’ is the name given to the most obsessive sommeliers: the kind of oenophiles who lick rocks to train their palate, who refer to 10 a.m. tasting sessions as “tongue cardio,” and who can name not only the grape and region in which any given wine was produced but can also tell you the weather during the year it was grown,” write Nicola Twilley and Cynthia Graber (The Atlantic). Cork Dork tells the story of [Bosker’s] transformation from wine novice to pro, as well as diving deep into the neuroscience of smell training, the economics of wine pricing, and the history of the sommelier, from Roman sex slave to today’s cellar rats.”

“Bosker was an executive tech editor at the Huffington Post, but left to explore the all-consuming world of wine, determined to explore how and why sommeliers—or cork dorks—push themselves so hard in the name of fermented grape juice,” writes Jessica Yadegaran (San Jose Mercury News)

Cork Dork earns a starred Kirkus Review:

Bosker made her way into a couple of blind tasting groups, where she met a wine mentor who coached her for the competition; traveled to California to view the production of mass-market wine; talked her way into a wine “orgy” for the mega-rich; and met with the inventor of the “Wine Aroma Wheel,” a “circular chart of six dozen descriptors.” Always perceptive, curious, and entertaining, the author describes her experiences with precision and a wry sense of humor, locating the exact words to evoke even the most insubstantial sensations.

Jennifer Senior (New York Times) calls Cork Dork “a compendium of bewitching and sometimes disgusting facts. (There’s an art to spitting, apparently.) Do ignore the subtitle, which is filled with about as many additives as your average plonk, and every bit as cloying. It’s deceptive. Bosker’s journey into this sodden universe is thrilling, and she tells her story with gonzo élan.”

Paul Watson, Ice Ghosts: The Epic Hunt for the Lost Franklin Expedition

The Pulitzer Prize winning photojournalist was with archaeologists who located the Erebus, one of two sunken ships lost in the doomed 1845 Franklin Expedition a few years back. “It’s chilling really to look at it,” he tells NPR’s Steve Inskeep. “The ship is almost completely intact. The only thing that’s missing is her three masts, which presumably had been sheared off by moving ice over the years.” His book combines the story of the expedition with the ultimately successful search for the long-lost ships.

“Britain’s Sir John Franklin set out in 1845 with two ships and 128 men to seek an open trade route through the Arctic to the Pacific—and disappeared,” writes Kim Ode (Minneapolis Star-Tribune). “Not until 2014 and 2016 were the Terror and Erebus finally discovered, sitting upright on the ocean floor, the culmination of decades of work by dozens of searchers. Paul Watson, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, tells how Inuit lore, British pride and modern technology often worked at cross-purposes, and also how people, sometimes for no logical reason, became obsessed with the ill-fated expedition.”

“Why all the interest in HMS Erebus and HMS Terror?” asks Bill Streever (Dallas Morning News). “Because the search for these two vessels, in a very real sense, has continued more or less nonstop since they failed to emerge from the Arctic in 1847. It was a search with many twists and turns, with false leads and dead ends. Its cast of characters included a bereft but determined widow, the Royal Navy, whalers, psychics and ghosts, sled dogs and arctic foxes, Inuit Eskimo oral histories and sophisticated electronics, independent explorers operating on a shoestring, a software billionaire, and the Canadian government. And it was a search that offers insights into the worlds of Arctic exploration, marine archaeology and the bureaucracies of government and science.”

David B. Williams (Seattle Times) concludes:

Watson eloquently shows, particularly through Inuit historian Louis Kamookak and his search to discover what his relatives and elder Inuit knew, that if only the many generations of Franklin searchers had thought to ask, then the great mystery of Franklin might been have solved decades ago. This final section of the book is when Watson’s story shines. It is also what makes his story different and more valuable than most of what comes from the cottage industry of Franklin books.

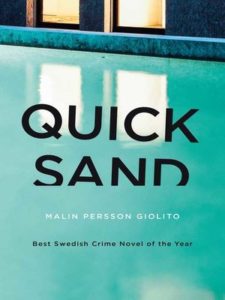

Malin Persson Giolito, Quicksand

The Swedish author’s first book translated into English is a courtroom procedural that dissects contemporary Swedish class differences. Its narrative voice captures critics.

Lidija Haas (New York Times Book Review) writes:

The first of Malin Persson Giolito’s four novels to be translated into English, Quicksand is also the first to be told from the perspective of a defendant rather than a lawyer….What we’re reading here is not so much Maria’s unfiltered thoughts as her speech to an imaginary audience: Mostly we listen in as she tries to make sense of what happened, but she occasionally addresses us directly, speculating as to what assumptions we might make about her and what comfy delusions we may be harboring about ourselves. The voice is uneven, unpredictable in a way that feels characteristic of a teenager—Maria is scathing in her dissection of other people’s clothes, habits and pretensions, yet she also sometimes slips into sentimental reveries about her 5-year-old sister: “I dream that she places her little hand, light as a birch leaf, on my arm, looks at me, and asks why.”

“Giolito, who practiced law before she turned to fiction, writes with exceptional skill,” writes Patrick Anderson (Washington Post). “She seems to know everything about Stockholm’s rich and the ways of teenage girls. Her story examines the corrosive effects of vast wealth. Even the novel’s title, Quicksand, suggests a world that will suck in, swallow and devour the unwary.”

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.