5 Books in Translation You May Have Missed in April

Bethanne Patrick Recommends Bruno Lloret, Eva Meijer, and More

As you’ve seen in the past few months, sometimes I find a theme while I’m ferreting out titles for this column—thrillers in translation, e.g. Sometimes there’s no theme beyond literary excellence, which ties all five of the books here together, and also makes things really tough: at least 15 other books deserved to be included. At a certain point in this game of book criticism, you have to rely on your intuition, and I don’t mean intuition about which books are “the best.” (If that were the case, I’d have to read several dozen for every column.) No, I mean intuition about which books I might best be able to describe and convince others to read. Here’s hoping my gut instincts were correct. Happy reading!

*

Bruno Lloret (trans. Ellen Jones), Nancy

(Two Lines Press)

Lloret’s debut, published in 2015 when he was just 25, won the Bolaño Prize, deservedly so, because the eponymous narrator’s urgent voice combined with the author’s experimental forms make Nancy a must read. Riddled with cancer and heavily medicated, Nancy has returned to her home in Chile to wait for death. But her consciousness has other ideas, returning her far back to a time in her life when joy was like ripe fruit within reach of her able fingers. Her memories arrive less like stream of consciousness than like moments of elimination (at one point she urinates for “three whole minutes, nonstop”), sometimes stopping at her alcoholic husband’s actions, sometimes at her awful mother’s abandonment of her family, sometimes at her father’s bolting with a pair of Mormon missionaries, sometimes going on and on about pain and loneliness but always with an edge that reminds you while Nancy may be dying her memories and experience are real.

Eva Meijer (trans. Antoinette Fawcett), Bird Cottage

(Pushkin Press)

Gwendolen Howard, known as Len by the humans in her life, chose at age 40 in 1938 to leave London for a small Sussex house and the company of birds. Eva Meijer, a Dutch philosopher who published When Animals Speak in 2019, beautifully imagines the decades in which Len Howard withdrew from the world and devoted her days to the care and companionship of avians. Not only does she cover her home with nesting boxes, name as many birds as possible, and feed them—she transcribes birdsong and teaches some of them to count. Meijer’s writing is solid, at times lovely and deft, but what makes this book stand out is less the prose than the deep understanding behind it. The author’s compassion for an eccentric and perhaps difficult person determined to understand a different species just might allow someone reading it to further understand our own.

Amélie Nothomb (trans. Alison Anderson), Thirst

(Europa Editions)

How many times do you read “international literary superstar Belgian novelist”? It’s a first for me, at least, and Nothomb’s 28th novel takes on another first: A fictional life of Jesus. “I always knew I would be sentenced to death. The advantage of such knowledge is that I can focus my attention where it is warranted: on the details.” Boom! From its arresting first lines to its final thoughts on faith and love, this slim novel shows us a funny, sly, and sometimes frustrated Son of God—during his trial presided over by Pontius Pilate, the Canaan bride and groom complain about how long Jesus took to turn water into wine, while Lazarus complains about how he always smells like death, and so on. In other words, Northomb takes the Son of God and turns him into the Son of Man, a very human Jesus whose attempts to cope with his fate actually make his story more powerful.

Eva Baltasar (trans. Julia Sanches), Permafrost

(And Other Stories)

In her “Translator’s Afterword,” Julia Sanches notes that Baltasar’s one ask of her translator be that they select words in English with similar stresses to those in her native Catalan. When you know that Baltasar is an accomplished poet, that makes sense. It also gives Permafrost a wonderful “uncanny valley” vibe; while reading it, you feel a subconscious clang of recognition and distance all at once. And because Baltasar is a poet, she also understands how to reinforce the musicality of her prose with twin themes: queerness and suicidality. No, she isn’t equating them. Instead, she’s showing how a queer, depressed woman’s development from adolescence to middle age feels, and how orientation can be a salvation, how love and eroticism can help lift the narrator out of her low mood. Readers won’t need to worry about low mood while reading this original, spark-y roman à clef, in which so many female family members ask the narrator what it’s like to make love to a woman that she finally answers them with the most unexpected analogy I’ve seen in a while.

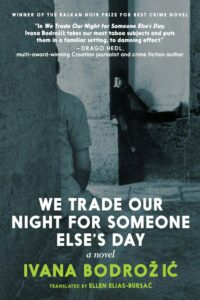

Ivana Bodrozic (trans. Ellen Elias-Bursac), We Trade Our Night For Someone Else’s Day

(Seven Stories Press)

Bodrozic, born in Croatia, was barely nine years old when the Yugoslav Wars began in 1991, when her father disappeared while fighting for their country’s independence, when she and her family wound up in a Kumrovec refugree hotel. She has written about this difficult history in two poetry collections, a short-story collection, an award-winning novel titled The Hotel Tito, and now, a political thriller in which Vukovar becomes a nameless city filled with damaged people who continue to damage each other. Report Nora Kirin, assigned to do a feature story about a Croatian teacher who fell in love with a Serbian student, then murdered her Croatian husband, has her own ghosts to avenge, and the deeper she delves into the teacher’s story, the deeper she becomes entangled in the city’s past. Don’t miss the Translator’s Note for an interesting explanation of the chapter titles, epigraphs, and section names, which come from a pre-1991 Yugoslav band, EKV.