5 Book Reviews You Need to Read This Week (Ron Charles Does Not Like the New Mitch Albom)

“Such soggy inspirational literature makes me seasick.”

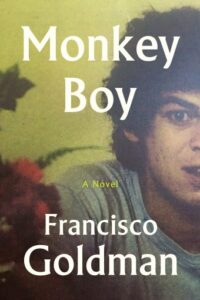

Our quintet of quality reviews this week includes Scaachi Koul on Emily Ratajkowski’s My Body, Julie Philips on Louise Erdrich’s The Sentence, Jennifer Szalai on Cathy Curtis’ A Splendid Intelligence, Ron Charles on Mitch Albom’s The Stranger in the Lifeboat, and Ed Morales on Francisco Goldman’s Monkey Boy.

Brought to you by Book Marks, Lit Hub’s “Rotten Tomatoes for books.”

*

“What an impossible task Emily Ratajkowski gave herself—it’s admirable, really, her efforts to better understand the arcane, patriarchal, racist, capitalistic measurements of physical beauty that have allowed her to be famous and successful and rich … Honestly, the whole book is pretty depressing, a constant push-pull between Ratajkowski’s self-awareness and the greater forces that commodified her … Ratajkowski’s clean, clear writing does what you want it to do; it wrestles with what it means to be conventionally attractive … Where Ratajkowski fails is in thinking more critically about her place in the world, in the continuum of women feeling bad about their bodies, being discriminated against for their bodies, being abused and assaulted for their bodies … The thing that she’s trying to understand in a more holistic, intersectional way is the very thing that has given her a good, comfortable life. I don’t begrudge her those moments of low self-esteem or the individuals in her life who seem to think she’s nothing but a body, but when taken in the larger context of fat-shaming and body discrimination, hers is an unfulfilling tale … My Body doesn’t give us any way to move forward, any idea what to do with our punishing self-hatred or the way men profit from women’s beauty … People are entitled to look however they want, Ratajkowski included, even if her body sometimes makes me feel bad about my own. That’s not her fault, per se—but she is an active participant in a system that raises her up and makes me hate jean shopping. That dichotomy is missing from her reflections … My Body doesn’t cut as deep as I want, but it cuts all the same.”

–Scaachi Koul on Emily Ratajkowski’s My Body (Buzzfeed)

“Darkly funny and wickedly brilliant … Erdrich’s great gift is for creating fully realized, fully human characters in complex and satisfying relation to one another … If you’d been wondering who was going to write the first Great American COVID-19 novel, you might not have guessed Erdrich, whose gifts of empathy and imaginative power aren’t the kind usually associated with hot takes on current events … The Sentence must have been written at high speed, and the haste shows, but what the book loses in tidy plotlines and a satisfying resolution, it gains in urgency and inventiveness. Rising from last summer’s ashes and honoring its ghosts, The Sentence is the perfect book to read right now, an unpolished, intense, politically passionate, sorrowful, comic masterpiece.”

–Julie Philips on Louise Erdrich’s The Sentence (4Columns)

“To be a literary biographer is to court the extravagant ridicule of the very people you write about. For all of the salutary services a writer’s biography can offer—the tracing of the life, the contextualizing of the work, the resuscitation of a reputation and the deliverance from neglect—the biographer has been derided as a ‘post-mortem exploiter’ (Henry James) and a ‘professional burglar’ (Janet Malcolm) … Curtis, whose previous subjects include the midcentury painters Grace Hartigan and Elaine de Kooning, has written the kind of straightforward, informative book that Hardwick frequently deplored—a ‘scrupulous accounting of time’ (as Hardwick derisively put it), a recitation of the facts that stretch across Hardwick’s long life, with scarcely little that truly captures the compressed intensity of the work itself. Still, the book is a start … Curtis assiduously chronicles the literary panels, the gossip and the ailments of Hardwick’s later years, before she died in 2007, observing the rhythms of Hardwick’s work while never quite falling into sync with them. But then a march is different from a dance, even if each has its own choreography.”

–Jennifer Szalai on Cathy Curtis’ A Splendid Intelligence: The Life of Elizabeth Hardwick (The New York Times)

“Such soggy inspirational literature makes me seasick. Everything about The Stranger in the Lifeboat is sketched in cartoon colors—from its vacuous theology and maudlin tragedies to its class warfare theme. Instead of character development, TV news reports interrupt the story to provide potted biographies of the lost souls. And the Lord’s statements supply all the holy insight of a sympathy card from your insurance agent. Panning a book like this may feel like harpooning a minnow, but I think treacly metaphysical fiction does us a cultural disservice. To borrow a word, it narcotizes people in search of real spiritual wisdom. That’s a shame because every religious tradition and many thoughtful writers of faith provide profound guidance through dark times of despair and grief. Cotton candy such as The Stranger in the Lifeboat is a saccharine substitute that spoils the appetite for sacred food.”

–Ron Charles on Mitch Albom’s The Stranger in the Lifeboat (The Washington Post)

“Throughout his fiction and nonfiction, Francisco Goldman has mapped the many border lines that pervade his life. Some of his novels have mined his Central American family connections. His journalistic work has uncovered the genocidal policies of the US government and its Guatemalan government collaborators. Sometimes he has adopted the detached demeanor of a forensic investigator looking into horrible crimes. Other times he has reveled in arch wittiness or an achingly sad prose filled with regret about personal loss, the kind that every human feels. His portrayal of his mixed identity, however, is not mired in lament about his tragic, internally warring selves, but rather is defined by a celebration of the fully realized intersections that make up an individual … Monkey Boy is a way to confront, work through, and even embrace these dark and unhappy legacies, to find meaning and joy in them.Monkey Boy has larger ambitions as well. It seeks not only to tell us a story set in ‘America’; it asks us whether there ever was such a place … Goldman at once explains how trauma is passed on through his parents’ experience of mid-20th-century America and—particularly through his passionate rejection of its ‘American Dream’ and the violence of American-backed dictatorship—offers an unsparing critique.”

–Ed Morales on Francisco Goldman’s Monkey Boy (The Nation)

Book Marks

Visit Book Marks, Lit Hub's home for book reviews, at https://bookmarks.reviews/ or on social media at @bookmarksreads.