5 Book Reviews You Need to Read This Week

"We all need—we all deserve—this vibrant, love-affirming novel"

Our feast of fabulous reviews this week includes Ron Charles on James McBride’s The Heaven and Earth Grocery Store, Katie Kitamura on Maya Binyam’s Hangman, Isaac Butler on Patti Hartigan’s August Wilson: A Life, Catherine Lacey on Ia Genberg’s The Details, and Charles McGrath on Steven Millhauser’s Disruptions.

Brought to you by Book Marks, Lit Hub’s “Rotten Tomatoes for books.”

*

“Ever since his memoir, The Color of Water (1995), became a fixture of American literature, there’s been an element of exuberance bordering on the miraculous in McBride’s work. Vitality thrums through his stories even in the shadows of despair … The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store confirm the abiding strength of McBride’s vernacular narrative. With his eccentric, larger-than-life characters and outrageous scenes of spliced tragedy and comedy, ‘Dickensian’ is not too grand a description for his novels, but the term is ultimately too condescending and too Anglican. The melodrama that McBride spins is wholly his own, steeped in our country’s complex racial tensions and alliances. Surely, the time is not too far distant when we’ll refer to other writers’ hypnotically entertaining stories as McBridean … If there’s a ramshackle quality to McBride’s plotting, it’s the artful precariousness of a genius. His expansive collection of ominous, preposterous and saintly characters twirls like loose sticks in a river, guided by a physics of chaos beyond all calculation except awe … We all need—we all deserve—this vibrant, love-affirming novel that bounds over any difference that claims to separate us.”

–Ron Charles on James McBride’s The Heaven and Earth Grocery Store (The Washington Post)

“Hangman is, among other things, a caustic rendering of immigration, diaspora and deracination. If the narrator is not at home in his adopted country, he is equally alienated from the country of his birth. That double displacement might be a familiar subject for fiction, but Binyam immediately short-circuits narrative expectation. From the start, it’s evident that America has been no land of opportunity, and that this visit will also be fraught with disorientation, a return without recuperation … A marvel of compressed unease, the novel is also wildly exuberant. This is in no small part due to the tensile strength of Binyam’s prose. Her style is simple and matter of fact, but full of unexpected pivots. She is also very funny. The novel is written with the kind of deadpan humor that makes you laugh even as it leaves you feeling a little queasy. The narrator himself is a primary source of this disquiet. Unflappable in the face of ever-increasing strangeness, he resembles Cary Grant’s character in North by Northwest, interpellated into a system against his will, buffeted by the waves of a wildly illogical narrative, the shape of which he cannot entirely perceive … There’s dark wonder in the final moments of this exhilarating novel, as the narrator gives himself over at last to both his fate and his longing.”

–Katie Kitamura on Maya Binyam’s Hangman (The New York Times Book Review)

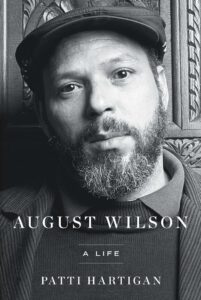

“It’s impossible to imagine American literature, dramatic or otherwise, without August Wilson. The playwright, who died in 2005 of liver cancer, transformed the American theater and created a new lyricism out of the black vernacular with a body of work whose ambition and expansiveness rival Walt Whitman’s … Yet his greatest invention may have been himself. Self-educated, self-named—he was born Frederick Kittel, named after a white father he barely knew and rarely acknowledged—Wilson was a legendary raconteur and a notorious fabulist. Both his greatness and his self-creation pose immense challenges to the would-be biographer. How do you see through the twin fogs of Wilson’s posthumous canonization and his habit of being untruthful about his life, in order to find the real man underneath? It is fortunate for us all, then, that we have Patti Hartigan’s masterful August Wilson: A Life. With painstaking research, stylistic verve, and an eye both admiring and exacting, Ms. Hartigan has pieced together the man behind the 20th Century Cycle, bringing Wilson to furious, complicated life … His early drafts were often a series of barely strung together monologues, with major plot incidents missing or underexplained. He required multiple fully staged productions to understand his plays and shape them into their final form. But oh, what final forms he conjured! … Ms. Hartigan has an eye for the perfect, telling detail … She isn’t afraid to take Wilson’s work to task, particularly in its portrayals of women, while also recognizing the unique power of his gifts. Ms. Hartigan also unearths plenty of juicy backstage gossip … Reacting to Wilson’s death, the playwright Tony Kushner told the New York Times: ‘Heroic is not a word one uses often without embarrassment to describe a writer or playwright, but the diligence and ferocity of effort behind the creation of his body of work is really an epic story.’ Finally, with August Wilson: A Life, we have an epic account to match.”

–Isaac Butler on Patti Hartigan’s August Wilson: A Life (The Wall Street Journal)

“Serious readers, after decades of filling their shelves, often notice that ‘some books stay in your bones long after their titles and details have slipped from memory.’ The unnamed narrator of Ia Genberg’s brief and penetrating new novel, The Details, is just such a reader, haunted by the nearly forgotten minutiae of the novels—and people—that have changed her life … The nonlinear structure of The Details means the narrator’s children flicker in the periphery as toddlers, then babies, then teenagers. She de-emphasizes her own parenthood as a way to recover some past part of herself that exists outside of being a mother, lover or friend. Books are so crucial to her inquiry because they cannot define the reader the way a child, husband or girlfriend does … The literal fever that begins the book mirrors the feverish beginnings and endings of these relationships, as well as the fever of reading — how it forces the reader inward, then leaves an invisible imprint in its wake. Genberg’s marvelous prose is also a kind of fever, mesmerizing and hot to the touch.”

–Catherine Lacey on Ia Genberg’s The Details (The New York Times Book Review)

“Steven Millhauser, whose new collection, Disruptions, is out just in time for his eightieth birthday, is the great eccentric of American fiction: a sleight-of-hand artist who from time to time seems to vanish into his own work … Millhauser reminds you of Borges sometimes, of Calvino and Angela Carter at other times, even of Nabokov once in a while. What sets him apart from other writers these days is that he’s a fabulist of a particular sort: his stories take place, for the most part, neither in the real world nor in one that’s wholly fantastical but someplace in between … The new collection includes a couple of excellent stories about dreamy, moony, self-conscious adolescents, another of Millhauser’s preoccupations. He’s written about them so often you can’t help guessing he must have been one himself. At the core of Disruptions, though, is a group of stories in a mode that Millhauser keeps returning to in book after book: a disorienting version of the small-town tale … All these stories are about transcendence—about a wish to get away from the worlds we inhabit and the limitations they impose on us … Much as Millhauser relishes the magical, he also has a soft spot for the humdrum: the sound of a lawn sprinkler, the sight of a basketball left on a driveway. His genius is to be able to evoke both so urgently. It’s telling that, in most of the Connecticut stories, the townspeople, after their flings with shadows or ladders or whatever, eventually come back down to earth.”

–Charles McGrath on Steven Millhauser’s Disruptions (The New Yorker)

Book Marks

Visit Book Marks, Lit Hub's home for book reviews, at https://bookmarks.reviews/ or on social media at @bookmarksreads.