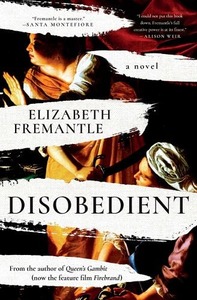

6 Difficult Women Who Live on in Fiction

Elizabeth Fremantle Rescues Misfits and Disruptors from the Wastebin of History

I like difficult women. They are the disrupters, the kind of women that break the rules and push the boundaries, the kind of women that are driven and ambitious and uncompromising, that take risks and are prepared to face the consequences—the Malala Yousafzais, the Rosa Parks, the Emmeline Pankhursts, the Katherine Parrs.

Though the women I just mentioned are (rightfully) widely known, many others have disappeared into the past, so I like to dig down into history and shake the dust off their stories. Often their achievements have been deemed inferior to men’s or their actions have been misrepresented by a history written by men. I have sought, in my own small way, to redress those injustices by shining new light on those women in my fiction.

Take Artemisia Gentileschi, the heroine of my latest novel Disobedient. She was one of the greatest painters of her day, an achievement that came at great personal cost. Despite the success she found during her lifetime, instead of becoming a household name like male painters of her time, she fell to obscurity. Her work was written off as unserious by dint of her sex. It is only now that she is gaining the respect she lost over time. Her story is fascinating, inspiring and profoundly shocking and it is my great hope that with Disobedient I can play a small part in giving her the recognition she always deserved.

Those are the stories that I am compelled to write and also the ones I love to read, so I’d like to share with you some of my favorite historical heroines in fiction.

Lauren Groff, Matrix

Matrix may be about a medieval nun, but quiet and contemplative it is not. Rather, it is a carnivalesque, thrilling and sometimes sapphic depiction of a unique and fierce woman. It is about power dynamics and desire and that woman’s unerring determination to shape her own world and make her mark on it. Marie de France was a 12th century poet and writer of fables, whose work is full of female cunning and occasionally strikes a surprisingly modern chord. Groff weaves beautifully the fragments of Marie’s possible biography into a beguiling and addictive narrative.

Maggie O’Farrell, Hamnet

We might have heard of Anne Hathaway but we’ve definitely heard of her husband William Shakespeare, who was strutting his stuff on the London stage while she was raising the children in rural Stratford. We know very little about her, except she was called Anne or Agnes, was some eight years older than Shakespeare, had three children—one who died young—and that her husband bequeathed her his second-best bed. This novel gives Agnes a voice and a heartbeat.

She is depicted as an outsider in the community, coming from a family that lives a little way out of town in the woods. She strides about with her falcon perched on her shoulder and is sometimes mistaken for a boy. The young William, engaged to teach Latin to her brothers, is beguiled. Hamnet depicts—beautifully, tragically—a community wretchedly infected by plague, the death of one of Agnes’s children and how she faced her grief. She is an unconventional woman, a misfit in her world, a woman who marches to her own drum beat and is entirely beguiling. I am a major fan of O’Farrell’s work, but I can dispassionately say that Hamnet is the novel of an author at the very top of her game.

Pat Barker, The Silence of the Girls

The Silence of the Girls tells the story of The Iliad from the perspective of the women of Troy, ripped from their homes to be enslaved by the besieging enemy. They are made to live in the soldiers’ encampment as the concubines of the warriors made famous by Homer. These women, mere shadows in that text, are brought to vivid life here—particularly Barker’s primary narrator, Briseis, won by Achilles as a prize, then stolen from him by Agamemnon, causing fatal conflict in the Greek camp.

Barker never balks from depicting the extreme violence of war. She weaves her narrative along Homeric lines yet shapes the conflict through the suffering and courage of the women, rather than the heroism of the men. Through Briseis’ story we are forced to face the grim fact that, even now, women continue to be used as the spoils of war.

Costanza Casati, Clytemnestra

Clytemnestra, a distinctly assured debut by classicist Costanza Casati, shines a light on a woman known for thousands of years as unforgivably wicked, having murdered her husband and thus continuing the cycle of revenge depicted in Aeschylus’s Oresteia. Casati offers us a new Clytemnestra, injecting her with humanity. Raised, as princesses were in Sparta, to wrestle and hunt, she is strong and steely and when she is pushed into marriage with Agamemnon, the man who murdered her beloved husband and son, and taken to far away Mycenae, she has no choice but to accept her fate.

But she does not forget or forgive, just as she does not forgive when her husband tricks her into delivering her daughter up for sacrifice to enable his war on Troy. In his absence Mycenae thrives under her rule while she waits and waits for his return, so she can mete out her revenge. Casati roots her Clytemnestra firmly in the real and gives a context to her actions. She is vigorous and tough and fascinating—entirely my kind of heroine.

Anni Domingo, Breaking the Maafa Chain

Did you know that Queen Victoria had a black goddaughter? I didn’t and it is likely that despite the great many things we do know about her personal life and her reign, you didn’t, either. Anni Domingo has redressed that void in history with her remarkable and profoundly moving novel, Breaking the Maafa Chain. This is fiction rooted in fact, in which sisters Salimatu and Fatmata, daughters of a West African chief, are captured by the slave trader King Ghezo of Dahomey. Fatmata is sold into slavery, while Salimatu is gifted to Queen Victoria. She is renamed Sarah Forbes Bonetta, dressed in western clothes and taken to England by Captain Forbes, an agent of Queen Victoria.

Domingo creates a fictional sister Fatmatu (renamed Faith), and describes her terrible fate as a slave, setting it against that of Salimatu. In doing so, she gives us two distinct stories of loss of identity. In the name of benevolence, Salimatu is stripped of her name, language and roots, to live the cossetted life of an aristocrat, while Fatmatu also has her roots ripped away but to exist in extreme hardship. We see that despite her apparently privileged life, Salimatu is as lacking in freedom as her enslaved sister. Maafa is the Swahili term for the African Holocaust and this novel illuminates this dark period of history, evoking beautifully the life and culture and lives they, and millions of others, lost.

Hilary Mantel, Bring Up the Bodies

What Mantel, an author of extraordinary skill and subtlety, has done in Bring Up the Bodies—in my opinion the best of her Cromwell trilogy—is give us a new portrait of Anne Boleyn. Henry VIII’s second wife has been more fictionalized than any other woman of that period, apart, perhaps from her daughter, Elizabeth I. There are so many versions of Anne – the temptress, the victim, the conniver – it is hard to gain a sense of what she might really have been like.

Mantel has excavated the historical record to find the politically canny Anne, the Reformation Anne, the Anne that made an uncomfortable ally of the coming man Cromwell, who would ultimately mastermind her downfall. This Anne is one who refused to be like other women but overplayed her hand and paid the ultimate price. Mantel’s depiction of her execution manages to balance being both heart-breaking, yet unsentimental. A truly extraordinary portrait of a remarkable and much maligned woman.

__________________________________

Elizabeth Fremantle is the author of Disobedient, available now from Pegasus Books