…

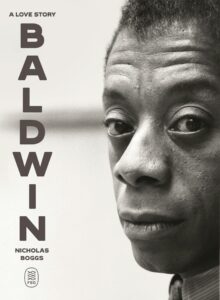

“If the consent framework does not provide substantive guidance, what might a more comprehensive sexual ethics look like? And could an expansive approach to the erotic domain promote sex that is not just blameless but fun? As the Georgetown philosophy professor Quill R Kukla writes in their thoughtful and refreshing new book, Sex Beyond ‘Yes’: Pleasure and Agency for Everyone, ‘We are obsessed with bad sex and how to protect against it, and we talk about that almost to the exclusion of good sex and how to have it.’

Kukla aims to fill this lamentable gap. Sex Beyond ‘Yes’ advances a vision of sex that is mutually fulfilling and respectful; more radically, it offers an affable defense of a good that our puritanical culture threatens to extinguish at every turn: pleasure, in all its glorious and indomitable disorder.

…

“All of this is plausible enough, and I have few bones to pick with the content of Sex Beyond ‘Yes.’ Its ambitions are admirable, its execution cheerfully competent. Yet Kukla’s bright, clean and rather infantilizing style is somehow incommensurate with the dark immensities of their subject. The register of analytic philosophy is curiously ill-suited to an activity that is—and ought to be—a toppling of all the usual defenses. Kukla is prone to cutesy phrases like ‘ninja-grade communication skills’ and exclamation marks, to anesthetizing what ought to ache.

…

“As Kukla observes, the challenge and the joy of ‘sexual communication’ reside in its stubborn oddity. Erotic language is closer to literary language than it is to language of the law. It is rife with euphemism and mischievous misdirection, with innuendo and performance. What makes it hard to do well is also what makes it hard to interpret and impossible to anatomize. But this is no more a reason to fall silent about sex than it is a reason to stop reading literature. It is only a reason to seek a stranger and less assimilable sort of speech.”

–Becca Rothfeld on Quill R Kukla’s Sex Beyond ‘Yes’: Pleasure and Agency for Everyone (The Washington Post)

“Oyeyemi, unlike her fatalist predecessors, conjures alternate realities. She swaps the dead-eyed liturgy of capitalist drudgery for something stranger—magic. Kinga suffers from a peculiar affliction: there are seven of her. Each takes charge of a day of the week, leaving voice memos and diary entries for the others; their texts and transcripts form the book.

…

“Helen Oyeyemi, the British Nigerian novelist who published her début at twenty, is an original—a writer whose style is equal parts mischievous, moony, and tart. Her books occupy the borderlands of realism and fable, where the plausible brushes up against the impossible, and the laws of narrative logic are bent just enough to let in the surreal. If the self-help cant of the title seems to glitch or stutter, the book’s contents shimmer with the same strangeness.

…

“Oyeyemi’s point, perhaps, is that every perspective is hopelessly partial. In these epistemologically treacherous conditions, the Kingas model how to proceed with curiosity and humility: ‘Maybe you see gentleness where I see joylessness,’ one Kinga muses, debating their shared therapist. Yet Oyeyemi sometimes seems to go further, endorsing a relativism so deep that even provisional consensus is out of reach.

…

“Yet in A New New Me, the virus has achieved self-awareness. There’s always been a flighty, avoidant streak in Oyeyemi’s fiction, as if she forever wants to be telling a different story than the one she’s begun.This novel is, in a way, about that very impulse: the lure of complexity as a means of escape.

…

“If Butler’s The New Me lampooned the self-improvement industry, Oyeyemi’s A New New Me pushes the logic of perpetual upgrades to the point that self-help is indistinguishable from self-erasure. It’s bloatware masquerading as betterment. Yet Oyeyemi doesn’t mourn the loss of unity or push for resolution. Is Kinga better off as one or seven? The book is agnostic. Some novels insist on being read as prescriptions for living; Oyeyemi’s simply depicts a process: one splinter of a soul briefly gains control of a body, and goes out to be engulfed by the world.”

–Katy Waldman on Helen Oyeyemi’s A New New Me (The New Yorker)

“Is escaping danger any different from escaping ourselves? And if we manage to do either, do we know where we are going? These are the kinds of questions that animate almost all of Lacey’s fiction, including her newest genre-bending work, The Möbius Book. Billed as a ‘memoir-cum-novel,’ it is Lacey’s first explicitly personal book, though it is a work of universal exposition as much as biographical recollection. Meditating on her life after a divorce, recalling her fraught religious childhood, and sorting through the reasons that she writes fiction in the first place, Lacey offers us an experiment in form but also in ideas. As the first half of The Möbius Book tells a fictional story about a friendship in which not all secrets are revealed, and the second half serves as a vehicle to reflect on the dissolution of a romantic relationship, Lacey presents us with a work that functions like a maze: Where exactly the exit is, and how we might navigate the abrupt, unexpected turns, will always remain a mystery.

…

“How else should we interpret a book that moves not chronologically or even logically, but betwixt itself? Part of the magic of The Möbius Book is that new metaphors and meanings emerge and come into focus as one reads its two different parts. As one reads book two after completing book one, for example, it becomes clear that Lacey shares much with Edie in the earlier tale.

…

“None of these supernatural references will surprise her longtime readers: In addition to formal invention, Lacey’s earlier novels abound with allegory, religious trauma, and spirituality. Yet one mystery remains unsolved in The Möbius Book: Amid its shocking, beguiling tales is that pool of blood. While we do eventually learn its likely cause, the explanation is so strange as to muddle our understanding of interpretation itself. But that, too, seems to be intentional. For if most of Lacey’s fiction is about running away from something or someone, in The Möbius Bookwe also get a study of how ignoring the past nearly always results in loss: not only of one’s tangible identity, but also of one’s coherence, orientation, and sense of meaning.

In this way, The Möbius Book is reminiscent of work by writers like Sheila Heti, Leslie Jamison, and Maggie Nelson. But in another way, the book is also something novel: While Lacey sets out to write both fiction and memoir tinged with universalisms, she resists combining the two genres explicitly; each has its own separate place in the work.”

–Alana Pockros on Catherine Lacey’s The Möbius Book (The Nation)