5 Book Reviews You Need to Read This Week

“Its quivering rhythms mimic those of a slow desert wind, picking up dust, chaff, and the bones of small mammals.”

Our feast of fabulous reviews this week includes Victor LaValle on Susana M. Morris’ Positive Obsession, Amanda Hess on Tarpley Hitt’s Barbieland, Saachi Khol on Olivia Nuzzi’s American Canto, Becca Rothfeld on John Darnielle’s This Year, and Bailey Trela on Forrest Gander’s Mojave Ghost.

Brought to you by Book Marks, Lit Hub’s home for book reviews.

*

“When writers, artists of any kind, attain a certain level of prominence, it can be easy to imagine that they were destined for their acclaim, that their greatness was inevitable. But that doesn’t serve them, or us. Instead, the portrait of Butler not simply as a genius, but as a human being riddled with insecurities and despair, is what makes Positive Obsession: The Life and Times of Octavia E. Butler by Susana M. Morris such a moving and welcome biography.

…

“Great writers, like Ralph Ellison and Toni Morrison, inspire esteem and even awe, but few, in my experience, are also able to provoke intimate identification, to seem like a person of great accomplishment who is also, somehow, deeply relatable in a personal way. Butler strikes me as such a writer, and Positive Obsession only served to deepen my affection. The book is a very fine examination of her books, how she wrote them, what inspired her, and the highs and lows of her career. But Morris’s most ingenious choice is to focus on the most personal elements of Butler’s life as well, evidenced by the journal entries quoted throughout.

..

“In her journal, Butler wrote: ‘I have no children. I shall never have any. American Black children will be mine. My fortune will be spent motivating and educating them while I live and after my death.’ Morris’s biography serves as proof that this goal was met. As does my career, and the careers of so many other Black writers I know who have, to varying degrees and across several genres, believed we could be writers because Octavia Butler proved it so.”

–Victor LaValle on Susana M. Morris’ Positive Obsession: The Life and Times of Octavia E. Butler (The Washington Post)

“The 2023 film Barbie begins with a parodic homage to 2001: A Space Odyssey. We open on a prehistoric desert landscape. Little girls in fusty dresses tend to a fleet of baby dolls. One wearily pushes hers in a creaky pram. Then a larger-than-life Barbie materializes, à la the monolith, in her original stiletto slides and strapless swimsuit. The girls are moved to rebellious action. They rip off their aprons and smash their baby dolls’ heads in. This is just the most recent and stylish retelling of Mattel’s central lore, which maintains that toy companies exclusively sold babyish dolls until the Mattel co-founder Ruth Handler dreamed up Barbie, freeing girls to center their imaginative play on an actual woman—as if it took this brilliant inventor to unlock their natural (and yet also progressive, sophisticated, even feminist) desire for a doll with breasts.

It’s a gripping pitch, though little of it is true. The real story of Barbie’s origins is much messier, and more interesting—especially as told in Barbieland, Tarpley Hitt’s rollicking tale of how Mattel spied, copied and stole its way to market dominance, then fought with military intensity to compel us to buy more and more. Barbieland is a book written from outside Barbieland’s high-security gates; we meet Hitt—an editor and contributor with The Drift magazine—as she’s being escorted off the premises of Mattel’s headquarters in El Segundo, Calif. Her book proceeds in a somewhat paranoid style, which is justified by its content. This is less an account of how Mattel made Barbie than an investigation of how Mattel wants us to believe it made Barbie, and the lengths to which it has gone to enforce this version of events.

…

“Parts of this story have been told before, as journalists and historians have worked, decade after decade, at disentangling Mattel’s regenerating promotional web. But Hitt has a special skill for enlivening the archive, and its gaps. She builds a propulsive story with players who double-delete their emails and burn confidential correspondence. She has an eye for the absurd detail, and she transforms toy executives into indelible characters whose lives are consumed by the cartoonish drama of competitive children’s entertainment.”

–Amanda Hess on Tarpley Hitt’s Barbieland: The Unauthorized History (The New York Times Book Review)

“American Canto was the last real opportunity for Nuzzi to talk about what happened: tangibly, what she did to torpedo her career and personal life. It could have been a pulpy tell-all that explains how she fell in love with the worst Kennedy or a political book opening up her reporter’s notebook to share from a vantage point few people ever reach. After these brief weeks around Christmas, already a chaotic time to publish a book, the interest around her will ebb. American Canto could have helped redeem her if only it were interesting.

Instead, it is illegible in ways you can’t imagine. Historians will study how bad this book is. English teachers will hold this book aloft at their students to remind them that literally anyone can write a book: Look at this, it’s just not that hard to do. Three hundred pages with no chapter breaks, it swerves back and forth through time, from Nuzzi’s interviews with Donald Trump over the years to her combustible relationship with fellow annoying journalist Ryan Lizza to her alleged affair with Robert F. Kennedy Jr. as he was running for president himself. Reading it is like spending time with a delusional fortune cookie: platitudes that feel like they were run through a translation service three times.

Written in a stream-of-consciousness flow, the book offers almost no insight into Kennedy as a person, as a politician, as a figure helping guide our collective political moment, or even into Nuzzi herself as a journalist once widely lauded and now largely seen as embarrassing. If you have not studied the intricate details of the pre- and post-exile life of a broadly connected 32-year-old reporter, the book’s contents are nearly incomprehensible, like hieroglyphics written in dust. For those who have been locked in on the Nuzzi gossip of late, it’s merely ham-fisted and tedious.”

–Saachi Khol on Olivia Nuzzi’s American Canto (Slate)

“I can’t remember the first time I encountered the great indie rock band the Mountain Goats, perhaps because to know them at all feels like having known them forever. Even on a first listen, their music has the redolence of a childhood memory, more like something forgotten and remembered than like something wholly new.

…

“It may sound as though This Year is of interest only to Mountain Goats obsessives—as I am firmly convinced anyone discriminating ought to be—but Darnielle is good company for everyone. He is charmingly digressive, and his frame of reference is dizzyingly wide, ranging from video games to professional wrestling to Italian filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini to German playwright Bertolt Brecht. Personal details emerge piecemeal, in no particular order, always in connection with the music with which they are entangled. One song, Darnielle tells us, is about ‘the Tasmanian tiger, the dodo, and the golden toad,’ three species that humans have tragically obliterated; another is about the time he ‘woke up handcuffed to a hospital bed’ after an overdose.

…

“The preponderance of Darnielle’s work is no less affecting than ‘The Sunset Tree,’ but it is more slyly allusive. To be sure, many Mountain Goats songs have something to do with Darnielle’s period as a methamphetamine addict in Oregon, his subsequent stint as a nurse in a psychiatric hospital in California, his four years studying classics and English at Pitzer College (I can think of no other band with as many songs about Euripides and Sophocles), his various moves across the country, his happy marriage, and his lapsed and then ambivalently unlapsed Catholicism (‘I tried to square my politics, which are radical, with the Church’s, which are a mixed bag’)—but the exact connections can be hard to pin down. They materialize mostly in ambiance and atmosphere, theme and tone. Darnielle writes often of desolation and addiction, and perhaps just as often of improbable bouts of grace, but he writes about them at a distance, in the guise of fictions—in an album about an alcoholic couple on the verge of divorce, in a song about a sinner who desecrates a church before pleading, ‘Let my mouth be ever fresh with praise.’

…

“To say that the Mountain Goats’ best songs are curiously bereft without the accompanying tumult is no insult to them. On the contrary, it is a measure of the full extent of their power. ‘This Year’ is no substitute for the live, thrashing artifacts. But the book is something else very worthwhile—an introduction to the sensibility behind a remarkable body of art and a chronicle of both the nearly fatal pain and the stubborn awe behind it. ‘I am glad I am alive,’ sings the narrator of the 1994 song ‘Going to Tennessee.’ I am so, so glad that Darnielle is alive, too.

–Becca Rothfeld on John Darnielle’s This Year: 365 Songs Annotated (The Washington Post)

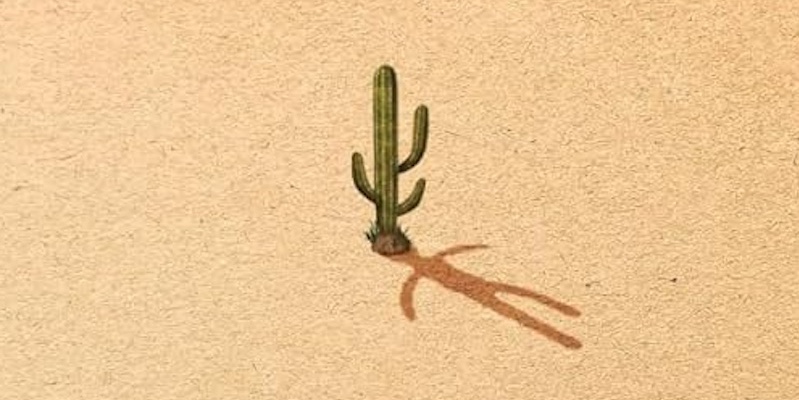

“Forrest Gander is on good terms with the mineral world, and he’s made a habit in his poetry of displaying a deep familiarity with the layers of sediment below our feet. His expertise—Gander is a geologist by training—has allowed him to convert technical terms (such as rift zone, ilmenite, and olivine) into lyrical tools that capture rarefied emotional states and complex systems of relation. So it’s natural that his latest collection, Mojave Ghost, opens with an act of geophagy. ‘The first dirt I tasted was a fistful of siltstone dust outside the house where I was born in the Mojave Desert,’ Gander writes in a brief preface. The dirt, the rocks, the minerals that make up the earth around him are an index of intimacy, of a time and place that shaped his fluid sensibility. Melding the human and nonhuman realms becomes an act of self-recognition for Gander, granting a deeper understanding of himself and the setting of his birth. But Mojave Ghost is an elegy, too, and the grief Gander expresses here is another form of intimacy we might develop with the earth. His mother, who passed away in 2020, is the titular ghost…

…

“Over the course of nearly four decades and 13 collections, Gander has evolved a poetics defined, first and foremost, by its thematic and formal hybridity: It’s a poetry of transfusion, obsessed with the crossing of borders between mediums, between the animate and inanimate. A proponent and sometimes practitioner of ecopoetry, Gander is committed to describing the natural world while simultaneously frustrating an anthropocentric reading of it.

…

“A long, continuous poem in blank verse and with no set stanza structure, Mojave Ghost moves at a meditative crawl. Its quivering rhythms mimic those of a slow desert wind, picking up dust, chaff, and the bones of small mammals—a sort of primordial accumulation.”

–Bailey Trela on Forrest Gander’s Mojave Ghost (The Nation)

Book Marks

Visit Book Marks, Lit Hub's home for book reviews, at https://bookmarks.reviews/ or on social media at @bookmarksreads.