5 Book Reviews You Need to Read This Week

Of Novels by Cormac McCarthy, Philip K. Dick, Barbara Kingsolver, and More

Our trove of terrific reviews this week includes Adam Rivett on Cormac McCarthy’s The Passenger, Leo Robson on John Banville’s The Singularities, Ron Charles on Barbara Kingsolver’s Demon Copperhead, and Molly Young on the novels of Philip K. Dick.

Brought to you by Book Marks, Lit Hub’s “Rotten Tomatoes for books.”

*

“… a sprawling, surreal affair, a book as strange as any he’s ever written, and reminiscent of the melancholy drift and God-haunted monologues of McCarthy’s earliest novels, published half a lifetime ago. While in precis a thriller, this isn’t No Old Country For Old Men. No gun is fired, no blade drawn from its sheath. This is more digression than headlong chase … Almost everything about the novel’s first hundred pages generates expectations for something tough, lean and violent…And then—beautifully, mysteriously, and somewhat bafflingly—we get another book entirely … Even while flouting expectations, McCarthy’s fundamentals remain undeniable. He’s a writer of both wonderfully taut and often very funny dialogue, and this is a book full of talk, bouncing from jokey drunk chat to near-baffling stretches of monologic erudition … Above all else, he is a prose stylist without peer … On almost every page some Faulknerian dazzle finds you, and while his language verges on the purple or overripe, it’s thrilling to return to writing as unashamedly biblical and rhetorical as this, when compared with the dutiful sentences and sturdy, balanced paragraphs of contemporary prose … Less successful is the book’s occasional dabbling with mathematics and physics … The novel comes to life most vividly when it drops this baggage and instead of gesturing towards darkness, embodies it through Bobby … Perhaps fittingly for a book about someone driven to stasis by mourning, the book feels inside out, forever discussing people not there, matters from the past half-explained. Both Bobby and finally the book feel a little withholding, as if we’ve been granted permission to only witness loss, without directly accessing its source.”

–Adam Rivett on Cormac McCarthy’s The Passenger (The Sydney Morning Herald)

“The Irish novelist John Banville writes prose of such luscious elegance that it’s all too easy to view his work as an aesthetic project, an exercise in pleasure giving…But what drives Banville—and his relentless hunt for the ideal adjective and simile and cadence—is a desire to touch something elusive and not quite nameable while providing a parallel or overlapping commentary on that doomed but never pointless effort. Although he is often compared to Nabokov, with particular reference to his arch and swaggering narrators, and an emphasis on doubles, Banville’s most important debts are to literary-minded German thinkers (Nietzsche, Heidegger), philosophically inclined German writers (Kleist, Rilke, Hugo von Hofmannsthal) and others in that line of descent, notably Beckett and Wallace Stevens … The Singularities, Banville’s exhilarating new novel, offers itself quite overtly as a rumination on, or rummage around, ideas about representation. Like much of his best work, it aims to both scrutinize and confront one of the central challenges of the human endeavor: how to create an accurate portrait of things … Banville is taking advantage of the breakthrough posited in The Infinities to create a universe inhabited by virtually all of his creations. But this isn’t merely a conceit or addendum along the lines of Paul Auster’s Travels in the Scriptorium. Banville has found a form that mobilizes his most cherished theme—the slipperiness of reality.”

–Leo Robson on John Banville’s The Singularities (The New York Times Book Review)

“Teddy lived long enough for his flaws to be fully exposed. All are laid bare in this book—the drinking, the infidelity, the selfishness, the casual cruelty, the emotional isolation. The central riddle of Kennedy is how these weaknesses existed alongside the benevolence, loyalty, perseverance and wisdom that made him one of the most influential senators in modern American history … More than just a personal profile, Farrell’s book revisits the origins of policy debates that still divide the country … Farrell mined historical archives from North Carolina to Kansas to California and many points in between. The result of his research is nearly 600 pages—not counting an extensive index and collection of source notes—that burst with detail … Farrell manages to unearth new tidbits about one of the most scrutinized lives in American politics.”

–Chris Megerian on John A. Farrell’s Ted Kennedy: A Life (The Los Angeles Times)

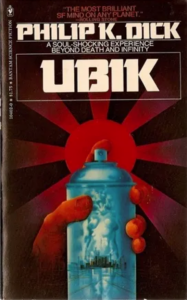

“The K stands for ‘Kindred.’ It was a family name, but if there’s anyone who can forgive a fanciful imputation of significance, it is Philip K. Dick. How lovely that a poet of alienation would come into existence bearing that word … The best of his work is fueled by nuclear-strength imagination, grand metaphysical and theological explorations, and prescience in matters of technology, marketing, consumerism, media and ecological catastrophe. Dick picked up on sinister cultural undercurrents the way a cat senses a can of tuna being opened six rooms away … The novel’s themes of entropy and delusion will swirl in your subconscious like a malevolent cone of soft serve. If I could propose two essential qualities of Dick as a human, they would be cosmic bafflement and heroic hopefulness, both present in Ubik. This is a novel with a long half-life. You may not clock the full effects until you find yourself thinking about it six or 60 months later.”

–Molly Young on the novels of Philip K. Dick (The New York Times)

“Equal parts hilarious and heartbreaking, this is the story of an irrepressible boy nobody wants, but readers will love … Demon is right about America’s condescending derision, but he’s wrong about his own worth. In a feat of literary alchemy, Kingsolver uses the fire of that boy’s spirit to illuminate—and singe—the darkest recesses of our country … Kingsolver hasn’t merely reclothed Dickens’s characters in modern dress and resettled them in southern Appalachia, the way some desperate Shakespeare director might reimagine A Midsummer Night’s Dream taking place in an Ikea. No, Kingsolver has reconceived the story in the fabric of contemporary life. Demon Copperhead is entirely her own thrilling story, a fierce examination of contemporary poverty and drug addiction tucked away in the richest country on Earth … Kingsolver has effectively reignited the moral indignation of the great Victorian novelist to dramatize the horrors of child poverty in the late 20th century … she’s raised the bar even higher, providing her best demonstration yet of a novel’s ability to simultaneously entertain and move and plead for reform.”

–Ron Charles on Barbara Kingsolver’s Demon Copperhead (The Washington Post)

Book Marks

Visit Book Marks, Lit Hub's home for book reviews, at https://bookmarks.reviews/ or on social media at @bookmarksreads.