5 Book Reviews You Need to Read This Week

"The book is a naked attempt by a twilight superstar to shore up his legacy"

Our fivesome of fabulous reviews this week includes Michelle Orange on Mary Gabriel’s Madonna, Becca Rothfeld on Werner Herzog’s Every Man for Himself and God Against All, Hugh Ryan on Justin Torres’ Blackouts, Charles Arrowsmith on Arnold Schwarzenegger’s Be Useful, and Jennifer Szalai on Fergus M. Bordewich’s Klan War.

Brought to you by Book Marks, Lit Hub’s book review aggregator.

*

“Suggests something comprehensive: it is eight hundred and eighty pages … Light on author interviews and other new source material, the biography is a towering work of assemblage, a guided tour through the origins and the creative life of ‘the enigma called Madonna,’ with a view to solidifying her status as a leading artist of her time. That there exists some doubt about this forms a subtext of the book, which, like any biography, proposes a fragile patchwork of contracts with the reader in the name of mastering its subject and fulfilling its brief … Gabriel, a former Reuters editor, organizes the chapters by dateline, taking an almanac-like approach, the idea being, more or less, that a thorough record of Madonna’s accomplishments will speak for itself. The result succeeds on the strength of that record and on the fine-toothed diligence with which Gabriel, who has claimed that she set out with no particular knowledge of or attachment to Madonna, combs through it. The tone is one of admiring dispassion, the approach at times discreet to the point of inertia. Readers hungry for original takes, fresh intel, or freewheeling analysis will remain so. Gabriel avoids risk and complication as fervently as Madonna has sought them out, spinning modest threads of historical, political, and cultural context that are never less than perfectly apt and rarely anything more … Though Gabriel emphasizes the relationships that have helped midwife Madonna’s work, she fails to make them intelligible: we get no sense of the artist’s grind, her habits and challenges as a songwriter, singer, producer, dancer, or director; or of how her vision and her ear have prevailed, in a decades-long evolution, through countless co-productions and genre dalliances. Old press-tour quotes on this subject are as illuminating as you might expect … More than her talent or her cunning, Madonna’s success reflects a public’s ambivalence about those freedoms we cherish, even as they frighten, bewilder, and enthrall us. Her story is that of an artist committed to remaking certain old ideals: beauty, sovereignty, connection, grit. It also tells of how starved we were, and still are, for their pure embodiment.”

–Michelle Orange on Mary Gabriel’s Madonna: A Rebel Life (The New Yorker)

“The book is nonlinear and exuberantly free-associative, less a narrative than an extravagant demonstration of sensibility … The book’s oddities will delight devotees of Herzog’s singular cinema, but readers unfamiliar with his tragicomic tirades and brooding philosophical meditations may find his digressions vexing … He recounts near-fatal exploit after near-fatal exploit with unwavering sang-froid, as if it is perfectly natural, even inevitable, to pursue the impossible to the brink of death … I got the impression that Herzog has not only never had a normal experience but that he has never encountered a normal person … Is any of this true? These marvelously magical remembrances may not be flatly accurate, but childhood is, most essentially, a land of terrors and enchantments, and a sober account of its charms would only serve to distort them. No one understands better than Herzog that, as he puts it, ‘truth does not necessarily have to agree with facts,’ that it is a matter of ‘poetic imagination.’ ‘The ecstatic truth’ is his wonderful name for the elusive quality he chases in his documentaries, which are not dry investigations but feats of storytelling with a distinctive point of view. In many ways, this is a shockingly impersonal memoir, but there is one sense in which Herzog is palpable in it. His melancholic, meditative and theatrically nostalgic way of being is as irrepressible in his writing as it is in his films. Sometimes, he verges on self-parody…But if Herzog is a fertile subject for satire, it is only because he is so inimitably and emphatically himself … I feel the same sense of awe when I contemplate the phenomenon of Werner Herzog as I do when I contemplate the pyramids. Amazing, that this fabulous impracticality exists. Amazing, that we go to such lengths to achieve such magnificent superfluities. Amazing, that we create such burdens for ourselves, and for no other reason than that, if we didn’t, we would be living dully, without the respite of our dreams.”

–Becca Rothfeld on Werner Herzog’s Every Man for Himself and God Against All (The Washington Post)

“…erasure poetry is much like queer history, a discipline that revolves around reading against the archive—mining biased sources for neutral facts, reading meaning into what isn’t said as much as what is, and flensing useful details off a rotten mass of lies. In Torres’s lyrical new novel, Blackouts, these two forms—erasure poetry and queer history—collide to create one epic conversation between a pivotal 20th-century queer sexology text and two unreliable queer Puerto Rican narrators … The further into the novel you go, the less ‘real’ everything outside Juan’s and nene’s stories seems. It is impossible to tell if ‘the Palace’ is a sad charity hospice for dying homosexuals, for instance, or some kind of queer bardo for gay ghosts. The supreme pleasure of the book is its slow obliteration of any firm idea of reality—a perfect metaphor for the delirious disorientation that comes with learning queer history as an adult … Torres haunts this book full of ghosts like a ghost himself, and with this novel, he has passed the haunting on, creating the next link in a queer chain from Jan to Juan to nene to you.”

–Hugh Ryan on Justin Torres’ Blackouts (The New York Times Book Review)

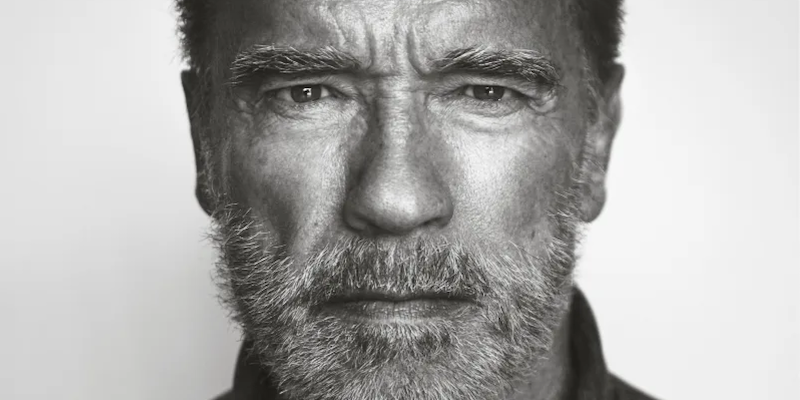

“Now 76, the five-time Terminator becomes a first-time Tony Robbins with the publication of his self-help book … Yes, like a moribund franchise, the Austrian Oak has been rebooted—this time as an elder statesman ready to dispense hard-won wisdom as abundantly as he once doled out movie death … His sensible guru era suggests that Schwarzenegger believes it’s temperance rather than bile that behooves an elder statesman and that the nation will eventually return to its senses. It also puts clear space between him and the parlous ghouls of today’s GOP, with its commando tactics and true lies. But what of the book? Permit me to save you the trouble of finding out for yourself: Be Useful is a raw deal, a hollow PR exercise filled with precepts and quips but devoid of self-awareness or humility. You might be swayed by Arnie’s touching faith in bipartisanship and the need to tackle the climate crisis or moved by his tales of heroic procurement of personal protective equipment during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. But as a pitch for Marcus Aurelius status…it’s thoroughly expendable—an overpromoted TED Talk, just another cross-promotional weapon in the Schwarzenegger multimedia arsenal … That the book is a naked attempt by a twilight superstar to shore up his legacy and project a new and benign vision of himself is abundantly obvious. Be not fooled: When Schwarzenegger talks of having vision, the ‘tunnel’ is silent.”

–Charles Arrowsmith on Arnold Schwarzenegger’s Be Useful: Seven Tools for Life (The Los Angeles Times)

“A vivid and sobering account of Grant’s efforts to crush the Klan in the South … For the most part, Bordewich’s narrative hews closely to the historical period, showing how federal power was the only way to stamp out local regimes that countenanced the suffering of Black people while allowing white perpetrators to go unpunished. For all their cries about ‘states’ rights,’ the Klan was unabashedly antidemocratic. Some Black Southerners, especially those who survived attacks or witnessed the violence firsthand, decided that they couldn’t bear the extreme risk of simply exercising their franchise. Bordewich includes some heart-rending testimony from freedmen who were too terrified to go to the ballot box. As one Black man put it, ‘I had to deny voting to save myself’ … Toward the end of the book, Bordewich gestures toward the fractured political landscape of the present day. Grant’s victory over the Klan is a story that many Americans would like to tell themselves, but the retrenchment that followed is a cautionary tale. A premature push for conciliation and compromise can leave the roots of some very old pathologies untouched, ready to grow again when the conditions are right. ‘Barbarism,’ Bordewich writes, ‘may lie only a small distance beneath the skin of civilization.’”

–Jennifer Szalai on Fergus M. Bordewich’s Klan War: Ulysses S. Grant and Battle to Save Reconstruction (The New York Times)

Book Marks

Visit Book Marks, Lit Hub's home for book reviews, at https://bookmarks.reviews/ or on social media at @bookmarksreads.