26 Maps Reveal a New York City Hiding in Plain Sight

From Rebecca Solnit, Garnette Cadogan, and Joshua Jelly-Schapiro's Nonstop Metropolis

Nonstop Metropolis, by Rebecca Solnit, Garnette Cadogan, and Joshua Jelly-Schapiro, is the final installment in a trio of atlases that imagines New York City through the unlikeliest of cartography, deploying 26 maps that trace the city from odd angles and unique perspectives. From the Bronx to Staten Island, Hell’s Kitchen to East New York, layer upon layer of the world’s greatest city is revealed through the insights and roaming eyes of writers like Garnette Cadogan, Teju Cole, Francisco Goldman, Margo Jefferson, Barry Lopez, Valeria Luiselli, Emily Raboteau, Astra Taylor, and many more. The excerpts below (along with details from the accompanying maps) present a New York City as yet unseen, but right in front of our eyes.

7.

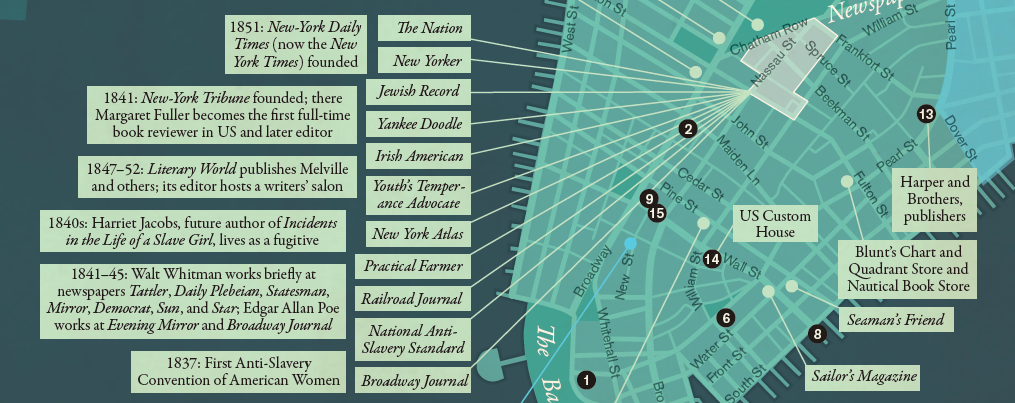

HARPER’S AND HARPOONERS

“The child is father of the man,” wrote William Wordsworth, and the mid-19th-century city is the mother of the current metropolis, or maybe its great-great-great-grandmother, unchanged when it comes to some buildings, utterly different in technology, economy, scale, population, and perception—though maybe something about loneliness and questing persists. Herman Melville’s Manhattan is not a lost city like Atlantis or Pompeii, but it is a place that has been mostly erased, from the vital shipping industry that fringed the lower island with a beard of piers, to the sailors’ haunts that were a prominent feature of the place, to the literary work done by whale light—by the burning of whale oil, which was a major source of illumination before kerosene and the age of petroleum and electricity, and the reason young Melville and legions of men from Nantucket, Hudson, and Long Island went hunting whales. What remains from that lost city is the powerful presence of publishing in the area, from the new headquarters of Condé Nast at One World Trade Center to those of Time magazine on Liberty Street. And some of the buildings and publishing houses there have had long lives. Two years before Herman Melville’s birth in 1819, James and Joseph Harper began a publishing operation that has spun off into the progressive Harper’s magazine, located at 666 Broadway (not far from where it began in 1850), and the mega-publishing house HarperCollins, now at 195 Broadway and owned by arch-conservative Rupert Murdoch, who also owns the New York Post (founded in 1801). It helped that Harper’s was the first commercial publisher in the United States to use the British-imported printing process called stereotyping, which enabled it to regularly print books in high volume. This, combined with people ready to market cheap books and readers ready to gobble them up, made New York the leading book-publishing city, and one that continues to employ technology to cultural ends and dominance.

11.

LOVE AND RAGE

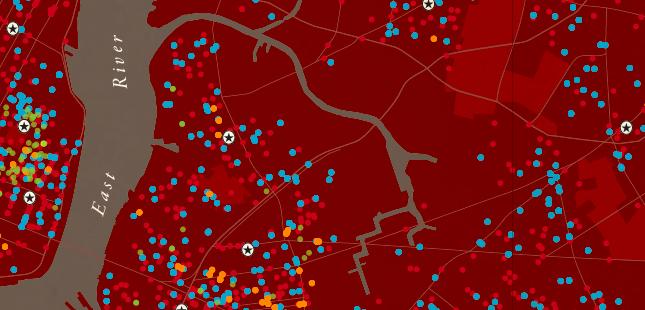

If the city is a living organism, then its streets and tunnels are vessels and bones: the physical structure that gives its body shape and keeps it moving. These built systems of concrete or steel aren’t hard to map, with the help of the right survey data or satellites. But if the city is a living organism, it also has emotions whose timbre and flow are as key to its health and function as they are to any human. These are harder to chart: not every force shaping our lives can be given discrete visual form or lent the weight of science. This map affirms that that’s true. But it also suggests how two emotions in particular animate this city, where the sheer density of humans can give rise to intense feelings of both love and rage. To name one well-known contrast of two of the city’s finest sons: Whitman loved the passing hordes in Lower Manhattan, while Melville often found himself annoyed by them. Both love and rage can manifest as an activity often associated with New York in particular.

Complaining is, if not an art form, at least an aria and sometimes a choral achievement in New York City, whose Yiddish-speaking population supplied us with the onomatopoeic word kvetch to cover it. Eloquent testimony to the richness and variety of complaints is borne out by the list at 311, the complaint hotline New Yorkers phone to address damaged trees, overgrown trees, streetlights, and toxic lead, as well as a host of other phenomena, including sacred noise, or “noise— house of worship” as it’s called, along with noise from helicopters, vehicles, and “street/sidewalk”; myriad animal problems, including “unsanitary pigeon condition,” “rodent,” “unleashed dog,” “animal in a park,” and “illegal animal sold”; “panhandling,” “poison ivy,” and “public assembly.” People call in out of empathic concern or annoyance or even fury, articulating a city categorized by concerns—although the less urgent ones, since the more urgent ones go to 911.

These emotions become forces shaping the city and responding to it. Love and rage could be imagined as attractions and repulsions, a set of invisible magnetic fields, of pushes and pulls, that direct our movements through a city, though violence may be the anomaly in this equation, the times when rage brings someone close enough to wreak damage rather than steering them away. We wanted to think big about love, since love of animals, of gardens and community and civil society, of justice, and of the city itself, as well as romantic and erotic love, shape how people act and where they go in the city. Sexual and gender violence might be where what is commonly classified as love warps into rage (though whether there was any love in the perpetrators is another conversation). Sifting through the city’s 311 data with Chris Henrick, a cartographer as skilled at “data scraping” as mapmaking, it became clear that some categories of activity were so common they were unmappable at this scale, except as a blur of color. Maps are an art of selection, and so out of the sea of emotions, reactions, and reports in response to the city’s everyday life we selected a few to suggest the range of civic-minded and antisocial action that is the everyday warp and weft of urban life.

The fact that the city breeds emotional extremes is also why it’s no stranger to romance: to fall in love while bathed in Gotham’s bright lights, against its unique backdrop of drama, is its own thrill. But love in the city doesn’t just mean romance—it means the love for community, evinced by those who turn vacant lots into gardens; the love for books and the public good, evinced by the city’s extraordinary system of libraries; the love for those young men and women who have too often been the targets of state violence, love that was voiced in the Black Lives Matter protests that erupted in 2014. The city makes us intimate in ways we desire and in ways we don’t. And with intimacy come all the human complications tied to love and rage, and the vexing place, too, where they twirl around each other and overlap—whether you’re on intimate terms with one person or eight and a half million of them.

15.

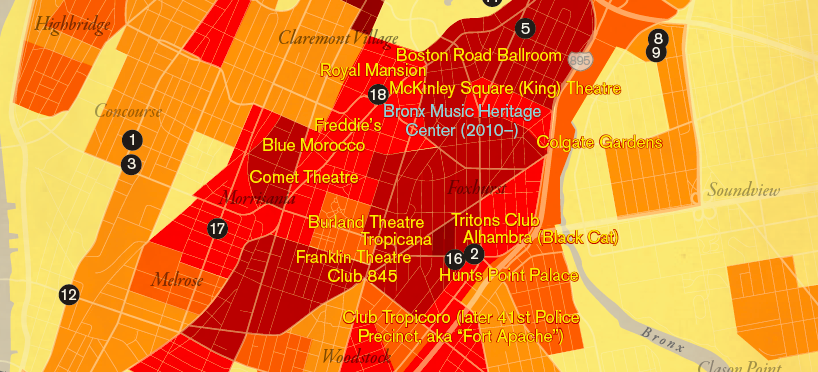

BURNING DOWN AND RISING UP

Langston Hughes, in the last book he wrote, depicts a child hearing grim news about the place where he plays and feels comfortable: “Misery is when you heard on the radio that the neighborhood you live in is a slum but you always thought it was home.” For people living in the Bronx, that is too often the experience: the media describe their home as a no man’s land or lawless Wild West. A borough of markedly different neighborhoods full of architectural delights, from the quiet waterfront community of City Island with its Victorian homes to the lively Grand Concourse Historic District lined with art deco beauties, the Bronx is too often caricatured as a burned-out wasteland.

The borough’s misrepresentation stems partly from an outbreak of fires that ravaged the South Bronx in the 1970s, leaving much of it rubble and many homeless. Residents were blamed for the devastation. But in that mess, kids found a way to achieve some measure of normalcy, remaking the landscape through a culture they would come to call hip-hop, creating beautiful, funky graffiti and sinuous dances, accompanied by infectious beats and catchy lyrics that provided a new soundtrack to the grim times. That culture and its “four elements”—graffiti, break-dancing, DJ-ing, and MC-ing—would quickly grow to become a lingua franca for global youth culture. By deciding to ignore other people’s reports about their home, these young innovators revealed how kids at play can burn with a determined fire that inflames the entire world for the better. Drawing on never-before-collated data on housing units lost to the fires, this map features the artwork of iconic graffiti pioneer Lady Pink, yet again hailing the borough through its remarkable story.

19.

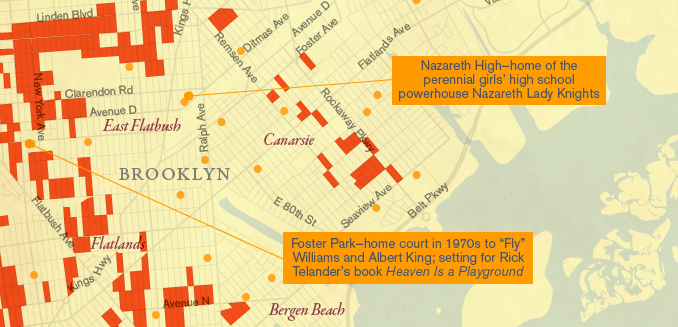

BROWNSTONES AND BASKETBALL

This is a city of icons—the life of its people is bound up in its symbols. This is a city of stoops. People greet the street and their neighbors from their doorsteps. The Dutch brought the stoop—derived from the Dutch word stoep, meaning the stone steps at a house’s entrance—to New York City, and its residents have used it since to exchange greetings, share laughter, ask “how your mamma be,” steal a kiss, or just rest and let the worries of the world evaporate in the cool of the evening. For a while, it was part of a popular game, stoop ball, in which a ball was thrown against steps rather than at a batter. It made the city’s brownstones more than architectural beauties—they doubled as sites of pleasure.

This is also a city of basketball courts. Just as one can get to know and more deeply enjoy one’s neighborhood from its stoops, as if the city were organized around them, so can one be more a part of the neighborhood by playing on its basketball courts. On those flat surfaces people also share laughter, assign affectionate nicknames, seek relief, and give themselves over to the energy of the city, flying elbows and bumps and trash talk notwithstanding. Basketball, “the city game,” has been as much part of New York City’s landscape as its majestic spires and regal brownstones. A pickup game became a way to know your neighborhood. (Before the displacement that is now sine qua non of economic development, the public courts had mainly neighborhood kids.) In these shared urban spaces you could be friendly without being friends. But with all the development since the 1990s, renovating old brownstones and removing neighborhood basketball courts, sights of neighborly playfulness seem to have become more infrequent. Sadly, the stoops and basketball courts of Brooklyn, where both frequently lay in close proximity, have now come to represent a sign of treasured things being lost.

21.

PUBLIC/PRIVATE

Public used to be a word that summoned up glory, and homage to the idea of the public was paid by buildings like Grand Central Station, the great cathedrals for everyday populism. The word shifted; the term public housing now brings up images of Bauhausian brutalism, danger, and neglect, though the 328 New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) residential complexes that accommodate 400,000 souls—the equivalent of the whole population of Tulsa or Minneapolis—constitute some of the greenest housing in the city. New Yorkers are exceptional among Americans in their reliance on public transportation and their possession of a great public transit system, in their grace at living in public among strangers while the denizens of many suburbs and sprawling cities cower in car-based and socioeconomically segregated spaces. In New York 1.1 million children are enrolled in one or another of the city’s 1,800 schools. You could celebrate New York as a capital of democratic public life, except that it is also the capital of the opposite. As a major world center for the transnational super-wealthy, it is the home of many of the architects of the attacks on the public sphere in recent years, and of course in that narrative Wall Street looms large. The new wealth is sometimes a direct incursion on public space, as when luxury towers on 57th Street put Central Park’s lower reaches in the shade. Sunlight literally becomes a private luxury, stolen from the park often seen as one of the nation’s greatest democratic spaces. The children of the elite travel in private cars, go to private schools, and have a host of luxuries, privileges, and enrichments thrust upon them, from specialists in packing for camp to SAT tutors to expensive party organizers and entertainers, as well as entrance into private spaces whose fees are steep. To read accounts of their lives is to recognize that their parents regard life as a brutal competition and anxiously try to keep their children ahead in the race with in-utero enrollments in the preschools that set them on the long road to elite success, with rewards all along the way. Equality is often imagined as a flat landscape, a level playing field; this is a map of Manhattan as a place as far from level as high-altitude luxury towers can make it. The public sphere is often magnificent in New York; the private sphere throws shade all over it.

From NONSTOP METROPOLIS. Used with permission of University of California Press. Copyright 2016 by Rebecca Solnit and Joshua Jelly-Schapiro.

Lit Hub Excerpts

An excerpt every day, brought to you by Literary Hub.