200 Years of Frankenstein On Stage and Onscreen

How Shelley's Tale Became Inseparable from its Film Incarnation

Few novels have spawned so many screen adaptations as Mary Shelley’s 1818 Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus. In the 200 years since it was first published, Shelley’s tale has been rewritten and reinterpreted so many times that it has become inseparable from its celluloid incarnation. From Gothic horror to spooky comedy, cinema has warped Shelley’s creation, building a Frankenstein mythos that extends well beyond the original text.

Just five years after Frankenstein was published, it received its first theatrical treatment with Richard Brinsley Peake’s Presumption! or, The Fate of Frankenstein. Shelley herself attended a performance and reported that, though she was “most amused” and the play “appeared to excite a breathless eagerness in the audience,” she thought the story “not well managed.” Peake’s adaptation was certainly a liberal one. He dispensed with the framing scenes of the novel, in which Captain Walton finds Victor Frankenstein pursuing his creature across the arctic tundra. He also reimagined the monster as mute (Shelley’s creature speaks with eloquence) and gave Victor the now legendary line, “it lives!” These amendments would be repeated in many subsequent adaptations, becoming accepted as “authentic” elements of the Frankenstein story.

1823 playbill advertising the opening night of Presumption; or, the Fate of Frankenstein.

1823 playbill advertising the opening night of Presumption; or, the Fate of Frankenstein.

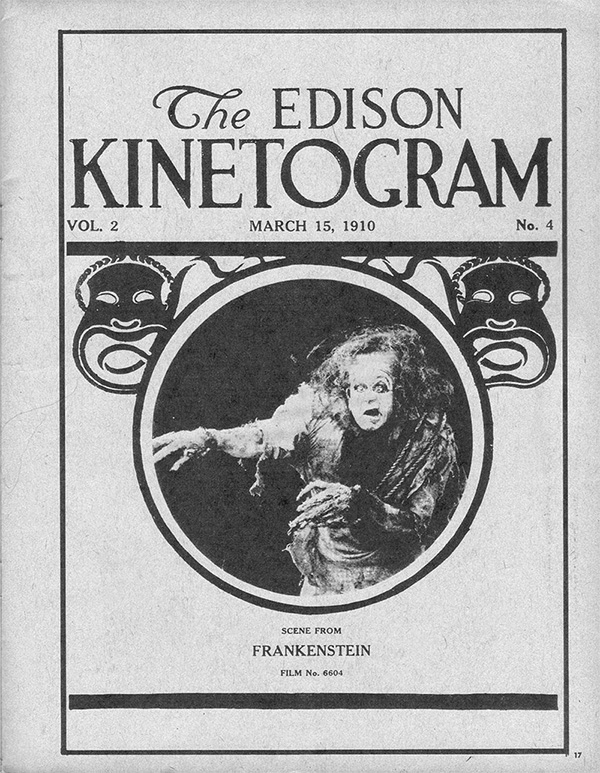

Frankenstein made its cinematic debut in 1910, in a short film directed by J. Searle Dawley for Edison Studios. The source material presented some issues for studio owner Thomas Edison who, believing that the success of cinema depended on “good moral tone,” was concerned that elements of Shelley’s story might be off-putting to viewers. He set about making the story more palatable, promising readers of his “semi-monthly bulletin” the Edison Kinetogram that his Frankenstein would “eliminate all actual repulsive situations” from the original story.

Cover of a 1910 The Edison Kinetogram film catalog, featuring the first motion picture adaptation of Frankenstein.

Cover of a 1910 The Edison Kinetogram film catalog, featuring the first motion picture adaptation of Frankenstein.

Edison’s film may have removed some “repulsive situations” but it dreamt up a whole new one: an eerie creation scene in which the creature emerges from a vast, burning cauldron of chemicals. The sequence was so ghoulish that many exhibitors refused to show the film. Given Shelley leaves the actual moment of creation undescribed, this was entirely avoidable. In the book, Victor is an enthusiastic student of science and mathematics, with a keen interest in electricity, but his precise methods are never detailed. Then again, what filmmaker could resist the high visual drama of a creation scene? From light rays to vats of amniotic fluid, filmmakers have continued to enthusiastically fill the gap left by Shelley’s text. Indeed, the omission itself might be one of the reasons Frankenstein is so appealing to filmmakers; this is one area of the story in which adaptations can take a legitimate free reign.

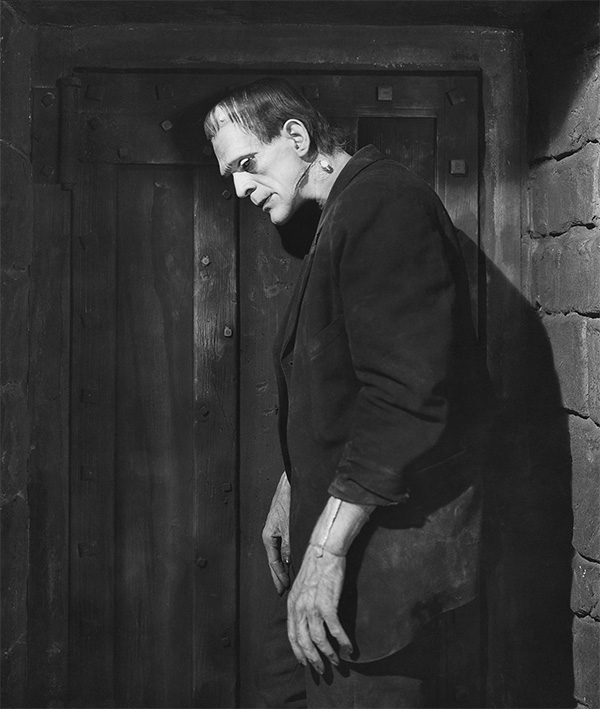

The physical appearance of the creature in Edison’s film is fairly loyal to Shelley’s vision. Hulking and long-haired, he echoes Shelley’s description of a huge creature with “lustrous black hair,” “watery eyes,” and a “shriveled complexion.” But it is another, less faithful, visualization of the creature which has become the iconic image of Frankenstein’s monster: that of Boris Karloff in James Whale’s 1931 film for Universal, Frankenstein. Enormously tall, with a squared-off head and two bolts to the neck, Karloff’s creature is a mute, brutish innocent. Though displaying rather less agency than Shelley’s creature (who is a more cognitively developed being) Karloff’s performance reflects the eerie melancholy of the book, producing a creature as sympathetic as it is frightening.

Boris Karloff in Frankenstein (1931), dir. James Whale.

Boris Karloff in Frankenstein (1931), dir. James Whale.

The film was a hit and the studio quickly produced a sequel, Bride of Frankenstein (1935), in which Victor creates a female companion for his creature. To those who haven’t read the book, the premise of Bride might appear a bit schlocky; the result of Hollywood producers seeking extra sex appeal for their cash-in sequel. But the seed of Bride actually lies in the third act of the book, in which the creature asks Victor to create a companion for him. When Victor refuses to complete the companion, the creature kills Victor’s bride in revenge. Whale’s film expands significantly on that idea, but the central conceit—that the creature longs for a female companion—is Shelley’s.

Boris Karloff and Elsa Lanchester in Bride of Frankenstein (1935), dir. James Whale.

Boris Karloff and Elsa Lanchester in Bride of Frankenstein (1935), dir. James Whale.

After Bride, Universal continued their Frankenstein franchise, veering away from the original story, first into ensemble monster pieces and eventually into comedy. Son of Frankenstein (1939) was followed by such offerings as Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man (1943), starring Lon Chaney Jr. as the Wolf Man and Bela Lugosi as Frankenstein’s monster, and House of Frankenstein (1944), which threw Dracula in the mix. Universal’s monster crossover fare was designed to appeal to the emerging youth market, but mixing Frankenstein with other canonical creatures was nothing new. Indeed, Frankenstein’s monster had shared the stage with vampires as early as 1887, when London’s Gaiety Theatre mounted the music hall production Frankenstein, or the Vampire’s Victim.

Frankenstein had its first comedy film outing in Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948), a film which foreshadows other comedic Frankenstein-inspired offerings, including Mel Brooks’ spoof Young Frankenstein (1974) and The Rocky Horror Show (1973). Horror adaptations continued, notably at Britain’s Hammer Studios. By the mid-1950s, Hammer had established itself as a home for low-budget romance films and thrillers. After a successful foray into science fiction, including The Quatermass Xperiment (1955), the studio turned to horror with The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) starring Peter Cushing as Victor (here styled as Baron Frankenstein) and Christopher Lee as the creature.

Curse was Hammer’s first film in color and this offered new opportunities for on screen gore; bright red blood is liberally splashed about, not least on the face of the monster, whose grey visage is covered in wounds (Lee likened the look to a “road accident victim”). It all proved too much for the British censors, who demanded that cuts be made—including a close-up shot of a severed eyeball—and even then only passed the film with an “X” certificate.

Curse of Frankenstein was a hit, and Hammer churned out six more Frankenstein films, including The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958) and Frankenstein Created Woman (1967). In matters of gore, however, Hammer’s efforts pale in comparison to Flesh for Frankenstein (1974), an Italian-French film produced by Andy Warhol. Flesh for Frankenstein is an orgy of sex and violence, in which Victor’s many depravities include pleasuring himself with the wounds of a dead body. Beaming its “X”-rated excesses to audiences in 3D, the film capitalized on newly relaxed censorship laws, but was still subject to heavy cuts.

Audiences were promised an altogether more faithful adaptation of the book with Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1994). Directed by Kenneth Branagh (who also stars as Victor), the film does cleave closer to Shelley’s narrative than many other adaptations. Branagh restores the framing scenes with Captain Walton, as well as scenes narrated by the creature. Nonetheless, the film is peppered with embellishments, including the resurrection of Victor’s dead bride, and it was not well-received.

Screenwriter Frank Darabont, who distanced himself from the project, felt that Branagh’s highly theatrical approach was ill-suited to Shelley’s more subdued text: “I don’t know why it had to be this operatic attempt at filmmaking. Shelley’s book is not operatic, it whispers at you a lot.”

Robert De Niro as The Creation in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1994), dir. Kenneth Branagh.

Robert De Niro as The Creation in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1994), dir. Kenneth Branagh.

Just five years after Branagh’s film, Frankenstein got a very different treatment in Universal’s direct-to-video Alvin and the Chipmunks Meet Frankenstein. Harking back to earlier cartoon Frankenstein fare, such as Hanna-Barbera’s Frankenstein Jr. and The Impossibles (1966), the film was one of several Alvin adventures to play on the studio’s monster movies. A few years later Van Helsing (2004), starring Hugh Jackman as the eponymous monster hunter, also paid homage to Universal’s horror heritage, featuring the character of Dr Frankenstein as well as Dracula and the Wolf Man.

Shuler Hensley as Frankenstein’s Monster in Van Helsing (2004), dir. Stephen Sommers.

Shuler Hensley as Frankenstein’s Monster in Van Helsing (2004), dir. Stephen Sommers.

More recently, Victor Frankenstein (2015) retold the story from the perspective of Igor (Daniel Radcliffe), a troubled circus performer who becomes an assistant to Victor (James McAvoy). Mixing and matching elements from the book and various screen adaptations, Victor Frankenstein was an unsuccessful attempt at a kind of Gothic buddy film. It bombed at the box office. This year, Frankenstein itself will take a backseat to its author in Haifaa al-Mansour’s biopic Mary Shelley, a film which focuses on the the writer’s romance with Percy Bysshe Shelley.

Adaptation has undeniably contorted perceptions of Shelley’s story. Indeed, one could see all these dramatizations as a kind of Frankensteinian narrative of their own, in which Shelley is undone by her creation, just as Victor was by his. But Frankenstein was a tale in flux long before cinema touched it. Even as the first adaptations were appearing on stage, Shelley was tweaking and revising her manuscript. The first edition in 1818 (in three volumes) was followed by a second in 1823 (two volumes) and a third in 1831 (a single volume, and the version most widely read today). The second edition was actually prompted by an adaption—Peake’s Presumption, which was expected to boost sales—and it included 123 amendments to the text.

In some sense, the countless reworkings of the story on screen simply reflect the novel’s own mutative life. Even if they do skew Shelley’s original vision, they are certainly testament to the enduring power and popular appeal of her story.

Iris Veysey

Iris Veysey is a curator and writer based in London. Her writing about art, film and culture has appeared in publications including Little White Lies, Article, Photomonitor, and The Observer.