17 Books to Read This November

Amphibious Creatures, the creator of Mad Men, Fake News, and More

Rachel Ingalls, Mrs. Caliban

(New Directions)

The subtle strangeness of Rachel Ingalls’ Mrs. Caliban—originally published in 1982 and now reissued by New Directions—exceeds its admittedly goofy premise, which is this: an unhappy housewife takes as a lover a six-foot-seven anthropoid amphibian. By marrying domestic realism with the literature of the bizarre, Ingalls brings tenderness to the monstrous and renders the recognizable utterly weird. Compact yet capacious, the novel wonders at all the ways we can desire and destroy one another. It’s unabashedly campy and deadly serious; it dares the reader to admit that these aims are not at all at odds.

–Nathan Goldman, Lit Hub contributor

Juli Berwald, Spineless: The Science of the Jellyfish and the Art of Growing a Backbone

(Riverhead)

Where good writing, science, and environmental studies converge, you’ll find me, even if it’s focused on an thing of my childhood nightmares: slithering jellyfish, sloshing in the salty waves. Juli Berwald, in her new memoir Spineless, shows how nature’s creatures—in this case, jellyfish—can provide information about our messed-up ecosystems, our persecuted environment, our overdeveloped landscapes, and the human condition. Maybe the jellyfish, rather than the bald eagle, should be our new national symbol, a harbinger of our own human failings.

–Kerri Arsenault, Lit Hub contributing editor

Ivy Pochoda, Wonder Valley

(Ecco)

Los Angeles glimmers and mystifies like the desert sun in Ivy Pochoda’s latest. A brilliant, rage-filled work of California noir, Wonder Valley opens amid morning bumper-to-bumper traffic. A naked man jogs past the beguiled commuters, sparking in each driver a slew of memories that we soon discover connects them all in intricate and dangerous ways. It’s a gritty but empathetic story, a vividly drawn panorama of southern California that fuzzes up at the edges as if the gray haze that creeps over the city during smog season has bled onto the pages. A must-read for fans of literary fiction that delves into the darker side of the Golden State.

–Amy Brady, Lit Hub contributor

Matthew Weiner, Heather, the Totality

(Little, Brown and Company)

Heather, the Totality is set to take us on a thrilling ride, following a wealthy Manhattan couple’s obsession with their “perfect” and virtuous daughter, and her inevitable pull towards a young man who they consider menacing and inadequate. This is the debut novel from Matthew Weiner, the mind behind Mad Men and an executive producer on The Sopranos. Given the mastery that he has shown at nailing toxic masculinity and classism, while telling exhilarating stories, I think we will be in excellent hands.

–Marta Bausells, Lit Hub contributing editor

László Krasznahorkai, The World Goes On, trans. John Batki, Ottilie Mulzet, and George Szirtes

(New Directions)

We know that László Krasznahorkai is at work on a major new novel set to publish in 2020, and there is still much in his rich backlist left to be translated into English. For now we can enjoy this recent collection, the most substantial English-language release for the Hungarian since the masterful Seiobo There Below. Global and local, philosophical and spiritual, clear-eyed and enraptured, pessimistic and optimistic, there is perhaps nothing more appropriate for this season of discontent than these 21 devilish pieces.

–Scott Esposito, Lit Hub columnist

Megan Hunter, The End We Start From

(Grove Atlantic)

We must be careful when reading this conflation of creation and flood myths that we aren’t lulled by its deceptive simplicity and exquisite aesthetic—both in language and physical presentation. Though Hunter uses lines from Eliot’s Four Quartets as epigraph and title, I hear Whitman—”Out of the cradle endlessly rocking.” As with all parables, The End requires the reader to participate. The asterisked interstices are to be filled with our knowledge of actual struggle, despair, redemption and renewal that we witness daily. As the child “Z” is born and carried over land and water, I filled the white space with a truth I knew: the visual of a 3-year-old Syrian refugee child dead on a Turkish beach. Z and his mother find community in each relocation; I see the Rohingya leaving certain genocide in Myanmar and wondering where they will find a welcoming community. Although Z makes it home, the home is moldy and the floor boards soggy. If there is redemption, it is in the fact that hope can exist in the greenery of a future forged from deluge and bullets carried on the inchoate forms of children. This is a hopeful book with a directive to trust. I really want to.

–Lucy Kogler, Lit Hub columnist

Caspar Henderson, A New Map of Wonders: A Journey in Search of Modern Marvels

(University of Chicago Press)

If you, like everyone else I know, could use a healthy dose of re-enchantment, I recommend Caspar Henderson’s magnificent A New Map of Wonders. A universe-spanning tour of the marvels of existence from mitochondria to the human heart to black holes, Henderson’s follow-up to The Book of Barely Imagined Beings joyously reminds us of the primacy and value of awe in a world sorely lacking it.

–Stephen Sparks, Lit Hub contributing editor

Camilla Grudova, The Doll’s Alphabet

(Coffee House Press)

As I tweeted when I first read The Doll’s Alphabet by Camilla Grudova, “This book has unspooled my brain.” Grudova’s combination of hoarder-like object obsessiveness and kick-ass feminist dialectic makes her short stories—one of them shorter than any flash fiction, some of them novellas-in-waiting—must-reads for anyone interested in the experimental and the dystopian. In Grudova’s world a sewing machine can be a woman, a weapon, a wish; on the other hand, a baby can be a sconce, a waxwork, or even a childlike adult. Whether she’s describing a set of earthly possessions sealed up in cans or a sentient spider’s fussy manicure, Grudova aims her fictional sword straight at the solar plexus of capitalist plenty in the face of the end times we all fear. Her book will, dare I say it, unspool your expectations about who tells stories, and how.”

–Bethanne Patrick, Lit Hub contributing editor

Nicola Pugliese, Malacqua, trans. Shaun Whiteside

(And Other Stories)

For Anglophone readers, 2017 has been bookended by newly-translated novels of surreal goings-on in Italian cities that were originally published in the 1970s. Giorgio De Maria’s The Twenty Days of Turin helped usher in the year; now, Nicola Pugliese’s Malacqua helps bring it to a close. Pugliese’s novel follows a journalist exploring a newly-flooded Naples and examining the strange phenomena occurring there, offering plenty of opportunities for surreal imagery and forays into the uncanny.

–Tobias Carroll, Lit Hub contributor

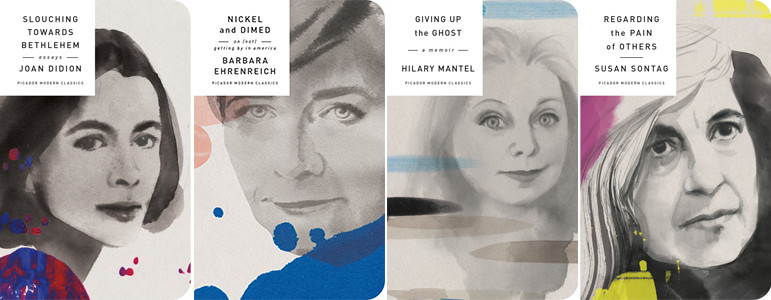

Picador Modern Classics

This month I’m recommending the latest in a modern classics series from Picador, cunning hand-sized editions of four nonfiction classics: Joan Didion’s Slouching Towards Bethelehem, Barbara Ehrenreich’s Nickel and Dimed, Hilary Mantel’s Giving Up the Ghost (“I hardly know how to write about myself,” she notes early in this memoir of her struggle with migraines), and Susan Sontag’s Regarding the Pain of Others. (The covers feature illustrations by Cecilia Carlstedt.) The Didion accompanied me during a surreal, unsettling and always unpredictable week-long evacuation during the recent Sonoma County wildfires, in which friends, family and strangers offered each other kindness, empathy and storytelling as a buffer against the devastation. I found it strangely comforting to read lines like “California is a place in which a boom mentality and a sense of Chekhovian loss meet in uneasy suspension.”

–Jane Ciabattari, Lit Hub columnist

Timothy Hallinan, Fools’ River

(SoHo Crime)

Poke Rafferty, Hallinan’s Bangkok-based travel writer, is one of the more unusual and engaging eyes in today’s crime landscape. Behind the high-octane adventures, there’s almost always an emotionally powerful family drama playing out. In Fools River, Poke’s sprawling family connections draw him into an underworld where the city’s foreign exploiters are preyed upon. This is the eighth novel in the series, and with each installment Hallinan’s world seems to get more complex and richly drawn.

–Dwyer Murphy, Lit Hub editor

The Graphic Canon of Crime and Mystery, Vol. 1, ed. Russ Kick

(Seven Stories Press)

Almost anything can be seen as a crime story, and almost anything can be adapted into a graphic novel. Few, however, have attempted such an ambitious and quirky melding of these two truths as editor and artist Russ Kick with his new anthology, The Graphic Canon of Crime and Mystery. This cleverly arranged series of graphic adaptations of classic mystery tales brings together a wide range of artists matched with a diverse list of stories, many of which are only loosely categorizable as crime fiction (that’s part of the fun of it). With everything from biblical judgements to decadent poetry to 19th century classics, Kick and his army of artists have crafted a formidable and fascinating collection.

–Molly Odintz, Lit Hub editor

Kevin Young, Bunk: The Rise of Hoaxes, Humbug, Plagiarists, Phonies, Post-Facts, and Fake News

(Graywolf)

In The Grey Album, Kevin Young explained how three types kinds of “shadow books” loomed over African-American culture: the ones that didn’t get written (as in, Jean Toomer or Ralph Ellison’s second novels), the ones that celebrate or highlight what was missing from their pages (Toi Derricotte’s work), and finally, the books that were written and lost. A list so long as to require a constant engagement with the past, to ask what we once knew but no longer do. In this sense, Young’s curatorial aesthetic—yoking blues poems, old recipes and legends into a modern poetic voice, anthologizing poets into volumes every few years—is not a nostalgia industry. It’s a response to what he sees pouring through the memory sieve of a culture stuck in revanchist ideas of African-American culture. “Bunk,” his profoundly erudite new study of the ways truthiness, as Stephen Colbert used to call it, travels through America’s fabric, continues this engagement.

Moving from P. T. Barnum to James Frey and then to the concept of race itself, Young unearths the ways this desire to have one pulled over on us, time and again, pulls from a “stock set of images, race, and gender stereotypes.” It is as if the big trick of a hoax is not impersonation, but the theft right before our eyes theft of “a claim for unimpeachable origins.” Young is a fabulous narrator. Ironic and informed, full of side-bars and anecdotes that only a man who has spent two-decades rummaging in a library will have at his fingertips. Read this book and you’ll suddenly see all the bunk in public view has antecedents in a past which itself was built on myths.

–John Freeman, Lit Hub executive editor

Louise Erdrich, Future Home of the Living God

(Harper)

I’m excited to get my hands on the new Louise Erdrich. Not only because she can almost always be relied upon to produce good—and sometimes great—novels, but also because this book sounds bonkers, in that special Handmaid’s Tale/surrealist-death-of-all-we-hold-dear kind of way. The book imagines that evolution has begun to spin backwards: the earth is turning prehistoric, and humans are beginning to give birth to pre-human babies—and as a result, the new government (the Church of the New Constitution) is rounding up all pregnant women, including Cedar Hawk Songmaker, who tells us this story. Even if this weren’t horribly topical, it would be at the top of my reading list. (Um, no pun intended.)

–Emily Temple, Lit Hub senior editor