17 Books to Read This February

Or How to Survive This Longest of Winters

Ali Smith, Autumn

(Pantheon Books)

I’m excited about Ali Smith’s Autumn. I’m usually excited about Ali Smith’s books, but this one is extra exciting because it’s the first of four volumes centered on the four seasons—so there are three more books to look forward to from Smith. Like How to Be Both, Autumn has tricks up its sleeve: A little magical realism here, a few pop-culture references there. Those are delightful, but as always, Smith’s real magic is in combining storytelling with meditation on deeper themes. Here those themes include belonging, identity, and memory.

–Bethanne Patrick, Lit Hub columnist

Ragnar Jonasson, Snowblind

(Minotaur Books)

It’s been a mild winter here in NYC, but the deep Icelandic setting of Ragnar Jonasson’s thriller Snowblind will send a chill up any reader’s spine. Jonasson’s rookie cop protagonist has taken a job in an isolated village and is unpleasantly surprised when a series of murders start as the snows relentlessly beat down. The first in a projected series, Snowblind is a top-notch, icy thriller, with a sympathetic hero and an unique setting. Bundle up and read.

–Lisa Levy, Lit Hub contributing editor

Sam Shepard, The One Inside

(Knopf)

Somewhat incredibly, The One Inside is the first work of long fiction from Sam Shepard, the Pulitzer Prize-winning dramatist whose writing career alone spans over a half century. The story of “a man in his house at dawn, surrounded by aspens, coyotes cackling in the distance as he quietly navigates the distance between present and past,” if The One Inside can capture even an ounce of of the bleak lyricism, dark humor, and tragic restlessness of Shepard’s best plays (see The Family Trilogy), then I’m sold. It’s also got a forward from Shepard’s old flame Patti Smith, which can’t hurt.

–Dan Sheehan, Book Marks editor

Raymond Roussel, Locus Solus

(New Directions)

Raymond Roussel’s Locus Solus could be accurately classified as an early science fiction story, a proto-surrealist novel, or a pre-Oulipo work of Oulipian “potential literature,” but the best way to describe it is to compare it—on both a literal and figurative level (in other words, in both plot and style)—to the wunderkammern so popular in Europe during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. These cabinets of curiosity housed strange artifacts—both ordinary and extraordinary, natural and supernatural, real and unreal—that titillated the viewing public. In Locus Solus, a man named Martial Canterel hosts a group on a tour of his estate where he shows off his uncanny inventions of ever-increasing intricacy, inducing feelings of both awe and horror. Like a retelling of Scheherazade’s 1,001 tales, but filtered through a character who fuses P. T. Barnum-style turn-of-the-century showmanship with a Dr. Frankenstein-esque mad scientist mania, these stories within a story are fascinating on their own but even more so in concert with one another. And they act as the text which shadows (without fully obscuring) an alternative text, a treatise on obsession and innovation, which always seems to bubble just below the dreamy surface.

–Tyler Malone, Lit Hub contributing editor

Sarah Manguso, 300 Arguments

(Graywolf Press)

“I don’t write long forms because I’m not interested in artificial deceleration,” Sarah Manguso writes in her new book. “As soon as I see the glimmer of a consequence, I pull the trigger.” 300 Arguments is the book of aphorisms that I’ve been waiting for: trenchant, witty, and sometimes absurd. “Think of this as a short book composed entirely of what I hoped would be a long book’s quotable passages,” she writes. Perhaps that’s why I’m so drawn to it: each nugget of wisdom is something I’m tempted to share on social media or email to a friend. Sometimes brevity is exactly what we need to make sense of the complicated world we live in.

–Michele Filgate, Lit Hub contributing editor

John Darnielle, Universal Harvester

(Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

Darnielle’s book begins with a scene in Video Hut, a small-town video rental shop before the days of digital downloads, where our protagonist Jeremy works. One day, a customer returns a video saying vaguely, “there’s something on it” referring to the interruptions she saw during the movie; parts of it are recorded over with grainy clips that feel menacing, even though they are hard to discern; they are as unsettling as the book’s cover—a sheaf of wheat backlit by a technicolor moiré. More customers find more clips until Jeremy can’t avoid viewing them himself. But it’s Darnielle’s elegiac prose combined with the realistic portrayal of a woebegone town in Iowa and its equally woebegone citizens that gives this book literary heft. The unpredictability of this video incubus clashes with the fixed lives of those who discover it and leads Jeremy (and readers) down paths we would probably rather avoid.

–Kerri Arsenault, Lit Hub columnist

Jessa Crispin, Why I Am Not a Feminist

(Melville House)

In this age in which it seems like nothing authentic can last longer than five minutes before being co-opted, feminism is top of the list. While we debate who was—and wasn’t—at the Women’s March and what the next steps are; while pop stars and brands keep dumping an apolitical vanilla version of the movement on us; and while we strive for intersectionality to become front and center of the movement—at last, hopefully—it is hard to know where we are. Author and critic Jessa Crispin, she of Bookslut (RIP), she of anarchic sewing circles and anti tong-biting interviews, promises this book is a “searing rejection of contemporary feminism and a bracing manifesto for revolution.” I am not sure where exactly she will go with it, which is why I plan on devouring this book as soon as possible.

–Marta Bausells, Lit Hub contributing editor

Richard Mason, Who Killed Piet Barol?

(Knopf)

Richard Mason’s Who Killed Piet Barol? is a finely textured, gloriously sensual, politically sophisticated and immersive follow-up to his History of a Pleasure Seeker. Mason follows Piet Barol from Holland to Cape Town in July 1914, where he and his wife Stacey pose as French aristocrats. Running low on cash, they come up with a scam. Piet will create distinctive furniture for a wealthy Capetown man, using wood from the forest of Gwadana, which he has learned about from two Xhosa men. Mason’s description of culture clashes—greed versus the sacredness of a forest the Xhosa believes houses the spirits of their ancestors—is vivid from both points of view. Piet glories in his creative musings within the forest. The Xhosa leaders and people are perplexed, endangered. Mason gives all creatures, including a leopard lying in the shade of a lime tree, conscious of the vultures, awaiting prey, a valued point of view.

–Jane Ciabattari, Lit Hub columnist

Pankaj Mishra, Age of Anger

(Farrar, Straus, Giroux)

Donald Trump is President! Britain is leaving the European Union! Everywhere you look, populists are riding waves of anger to victories that are sweeping competent, responsible governments out of power. What the hell is going on? Longtime LRB and NYRB essayist Pankaj Mishra has got some pretty good answers in Age of Anger. He goes all the way back to the 18th century, when these modern fires were just getting started, to explain the deep roots of our historical situation and draw parallels between what’s happening today and what happened throughout the 1800s and 1900s. A definite must-read if you’re trying to get your head around where the world is going.

–Scott Esposito, Lit Hub columnist

Claire Fuller, Swimming Lessons

(Tin House Books)

When I resurfaced from Claire Fuller’s debut novel, Our Endless Numbered Days, I knew I had found a writer whose career I would follow to the end—a day I imagine will never come given the timeless quality to her storytelling. If Swimming Lessons, her second novel, is anything like the first, then I look forward to diving deep into this world and resurfacing only to tell other readers of its rich thrill and lyrical beauty.

–Bianca Flores, Lit Hub editorial fellow

Lauren Elkin, Flâneuse: Women Walk the City in Paris,

New York, Tokyo, Venice, and London

(Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

In her contribution to The End of Oulipo?, Lauren Elkin brought together incisive cultural histories with smart sociopolitical commentary, turning the stuff of tight-knit literary communities into compelling reading. In her new book Flâneuse, Elkin takes on art and its context on a grander scale, looking at the relationship between women making art and the cities in which they worked and drew inspiration, encompassing everyone from Sophie Calle to Jean Rhys along the way.

–Tobias Carroll, Lit Hub contributor

Katie Kitamura, A Separation

(Riverhead Books)

Lingering doubts, disorientation, memories just out of reach, intimations of pleasure and dread—these are a few of the hallmarks of the modern continental mystery. Katie Kitamura, the author of The Longshot and Gone to the Forest, is American, but with her latest novel, A Separation, she’s working within the tradition of L’Aventurra, Modiano’s Honeymoon and other stories of existential sleuths drawn to Europe’s rocky coasts. A woman learns that her husband, from whom she is separated, has gone missing in Greece. She’s compelled to search for him. It’s a subtle, enticing premise, masterfully handled—the perfect read for a barren February weekend when a sunny clime seems the answer to all your problems.

–Dwyer Murphy, Lit Hub contributing editor

Viet Thanh Nguyen, The Refugees

(Grove Press)

As a follow up to his Pulitzer Prize-winning The Sympathizers, Viet Thanh Nguyen brings us The Refugees, a glittering and well-observed novel about the lives of refugees as they migrate between two worlds. We meet a young Vietnamese refugee who comes to live with two gay men in San Francisco, a woman who learns of her dying husband’s mistress, and a Vietnamese girl who reunites with her Americanized sister. At a time when the American federal government is questioning more than ever the value of refugees’ lives, this book is not only a moving read—it’s utterly necessary.

–Amy Brady, Lit Hub contributor

Junichiro Tanizaki, Devils in Daylight

(New Directions, trans. J. Keith Vincent)

Written in 1918, this slim, erotic work of suspense is a fine entry point for readers new to Tanizaki, whom Edmund White called “the outstanding Japanese novelist of this century.” A writer, Takahashi, receives a call from his psychologically troubled friend Sonomura, who claims to know when and where a murder will take place thanks to a secret cryptogram found within Poe’s The Golden-Bug. What enfolds is classic Tanizaki, an exquisitely atmospheric rumination on obsession, illusion, and the limits of fiction.

–Dustin Illingworth, Lit Hub staff writer

Mark O’Connell, To Be a Machine

(Doubleday Books)

What does it mean to be a machine—and, in turn, a human? Mark O’Connell’s new exploration of transhumanism, To Be a Machine, attempts to answer both questions. Transhumanism—famously deemed one of the world’s most dangerous ideas by Francis Fukuyama in 2004—is a controversial set of scientific and philosophical movements, all centered around escaping death by improving—and, eventually, discarding—our rather mortal fleshly bodies. By turns comedic, unsettling, ambivalent, and intriguing, To Be a Machine, which features trips to cryogenic facilities, biohackers’ homes, and more, casts a layman’s eye on transhumanism in the past, present, and future, braiding it to one of the biggest of the Big Questions: what does it mean to be a human? Although likely aimed more at people unfamiliar with transhumanism, O’Connell’s book is a worthwhile read for all audiences.

–Gabrielle Bellot, Lit Hub staff writer

Morgan Parker, There Are More Beautiful Things Than Beyoncé

(Tin House Books)

Full disclosure: Morgan Parker is one of the lights of my life, so I may be a bit biased but I am BEYOND excited for her second book of poems to drop. Morgan’s writing is sharp, assertive, and wise, and I love the way she uses humor (amongst other devices) to catalyze conversations about contemporary black American womanhood. Nothing in the world is off limits to her poetry, which inspires me every day.

–Tommy Pico, Lit Hub contributing editor

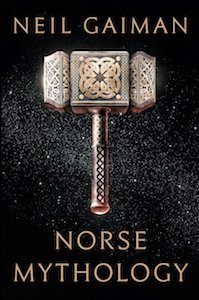

Neil Gaiman, Norse Mythology (W.W. Norton)

Though it feels like America is having its own little Ragnarok moment (“Is that a wolf eating the sun?”), settling in with Neil Gaiman’s retelling of all your favorite Norse myths might just be the way to get through this winter. Assuming there’s a spring.

–Jonny Diamond, Lit Hub editor