15 Books You Should Read This August

Whales, Royals, Comics, and More

Cixin Liu, Ball Lightning, trans. Joel Martinsen

(Tor Books)

The English translation of Cixin Liu’s The Three-Body Problem introduced one of China’s most beloved science fiction writers to the English-speaking world. Now the award-winning author is back with the thought-provoking page turner, Ball Lightning, translated by Joel Martinsen. It follows the story of Chen, who watched his parents become incinerated by an instance of ball lightning. What follows is a tale of intrigue and scientific inquiry, as Chen discovers what happens when science is conducted without consideration for its consequences. I’d been looking forward to this one all year.

–Amy Brady, Lit Hub contributor

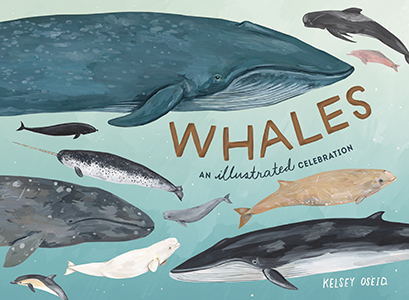

Kelsey Oseid, Whales: An Illustrated Celebration

(Ten Speed Press)

There are a lot of good books being published in August, including poetry collections from Etel Adnan, Ada Limon, and Forrest Gander, but I’m most eager to spend time with illustrator Kelsey Oseid’s book about whales, because, well, any excuse for celebration is a good one, but especially so if that excuse is whales. Covering all things cetacean—including evolution, behavior, family life, you name it—Whales: An Illustrated Celebration promises to be the perfect antidote to whatever horrors the world decides to dredge up this month.

–Stephen Sparks, Lit Hub contributing editor

New Micro: Exceptionally Short Fiction, ed. James Thomas and Robert Scotellaro

(W. W. Norton)

Thomas, who originated the Norton Flash Fiction anthologies (and the term for today’s popular ultra short fiction, based on witnessing a lightning strike) and flash fiction master Robert Scotellaro have pulled together a sizzling collection of 140 stories under 300 words from 90 writers, both established and emerging. Think Amy Hempel, Richard Brautigan, John Edgar Wideman, Diane Williams, Kim Addonzio, Stuart Dybek, Joy Williams, Amelia Gray, Ron Carlson, Bonnie Jo Campbell, James Tate, Joyce Carol Oates, Meg Pokrass, the list goes on. The perfect stories to read on your phone, read on the subway, read in batches or one at a time.

–Jane Ciabattari, Lit Hub contributing editor

Lisa Hanawalt, Coyote Doggirl

(Drawn & Quarterly)

Lisa Hanawalt is hilarious. See her first two comic collections, or watch her production design on BoJack Horseman, or listen to her podcast Baby Geniuses, “a show for people who know stuff and people who don’t know stuff, but would like to.” Or you can read Coyote Doggirl, Hanawalt’s first full-length graphic novel. Coyote Doggirl is a slapstick and churlish feminist western that subversively pays homage to classics like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and The Searchers. This book is smart, funny, and beautiful.

–Nathan Scott McNamara, Lit Hub contributor

Jon McGregor, The Reservoir Tapes

(Catapult)

A brilliant book about the social realities of a small English village, where 15 different bystanders relay 15 different perspectives in 15 different stories regarding the months leading up to the disappearance of a teenage girl. What’s also missing is evidence: there are gaps in the narratives, omissions in the retellings, and blanks in the conversations between the characters and the interviewer, who acts as the adhesive for and interpreter of the dissonant voices. McGregor insists the reader undertake some imaginative effort, and, as a result, we learn about ourselves by what we choose to augment, that silences can tell a story sometimes beyond words, and what happens when we simply don’t know the answers. A thriller of another kind, one where the writing is deft and the mood uneasy, this book illuminates the complexities of the human condition in a truly imaginative way. The Reservoir Tapes follows McGregor’s Man Booker long-listed and Costa award-winning book, Reservoir 13, about the same girl’s vanishing act.

–Kerri Arsenault, Lit Hub contributing editor

Raymond Queneau, The Blue Flowers, trans. Barbara Wright

(New Directions)

Time for you to get pataphysical with one of the weirdest and wildest rides in literature: Raymond Queneau’s The Blue Flowers, reissued by New Directions later this month. The Blue Flowers simultaneously tells the stories of Duke d’Auge as he romps through history and Cidrolin as he idles on the Seine in the ‘60s. As Cidrolin naps, the Duke takes center stage, and vice versa. Is each the dream of the other? With as much colloquial language as Joyce and Pound, as much bawdy humor as Shakespeare and Chaucer, and as much puzzle-like wordplay as any of his fellow Oulipo brethren, Queneau gives us an idiosyncratic masterpiece to enjoy, to study, to wrestle with for the ages. Someone once described it to me as “Twain on acid,” which is accurate even in its inaccuracy.

–Tyler Malone, Lit Hub contributor

Julie Schumacher, The Shakespeare Requirement

(Doubleday)

The Shakespeare Requirement by Julie Schumacher is a somewhat-sequel to Dear Committee Members. The latter was wholly epistolary and the former is not, making it slightly less snappy—but allowing it to be entirely more weird and true and wonderful. We’re back at Payne University with cranky Jason Fitger, the smartest and yet stupidest academic to walk the hallowed halls on the page since Richard Russo’s Hank Devereaux. The Economics Department continues its march towards taking over an entire building, leaving Fitger and his colleagues exiled to outdated, undercooled, and overheated offices. Anyone who has spent even a few days around a university English department will recognize the people, the arguments, the very desks. I am convinced Schumacher had my grad/faculty lounge in mind when she designed hers. If you’re looking for a late-summer read, this highly comic novel might be the ticket—however, don’t blame me if you are a little teary-eyed towards the end.

–Bethanne Patrick, Lit Hub contributing editor

Catherine Lacey, Certain American States

(Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

This month, I’m most excited for Catherine Lacey to turn to short stories in Certain American States. Two summers ago, I read her novel, Nobody Is Ever Missing, and I still vividly remember Elyria looking out at the ocean, thinking about how it’s weird that people consider it a beautiful thing when, really, it’s filled with animals eating animals, slaughter and decomposition. Peopled by widows, ex-wives, New York City transplants, and more, the stories in Certain American States find their characters at the crux of change and dare to probe their psyches as much as their surroundings. Here’s hoping for more under-the-surface carnage in this collection.

–Katie Yee, Book Marks Assistant Editor

Anna Moschovakis, Eleanor, or, The Rejection of the Progress of Love

(Coffee House Press)

Eleanor, or, The Rejection of the Progress of Love, the debut novel from poet and translator Anna Moschovakis, interweaves two equally entrancing narratives. One is the story of a writer negotiating her relationship with a domineering critic while struggling to revise her novel; the other is the novel itself, in which the protagonist, Eleanor, reels from the loss of her laptop and from some other, unnamed personal cataclysm. Together, the nested narratives invite us into a web of restrained ruminations on the contours of unmoored modern life. It’s a carefully controlled, intelligent novel of ideas.

–Nathan Goldman, Lit Hub contributor

Olga Tokarczuk, Flights, trans. Jennifer Croft

(Riverhead Books)

“Describing something is like using it—it destroys; the colors wear off, the corners lose their definition, and in the end what’s been described begins to fade, to disappear. This applies most of all to places,” writes Polish author Olga Tokarczuk in Flights while discussing guidebooks. But I fear this somewhat also applies to the novel and its sublime translation by Jennifer Croft (this collaboration earned them both the Man Booker International prize, which hopefully will mean more English translations of Tokarczuk’s other work; she is a bestselling author and household name in her native country). Flights merges mini-essays and personal and philosophical meditations on what it means to travel, to be in motion, with historical and fictional accounts of characters whose lives get tangled far from home. The latter read like gripping short stories, and the collage is moving and profound.

–Marta Bausells, Lit Hub contributing editor

Lesa Cline-Ransome, Finding Langston

(Holiday House)

For those of us who sell books, school summer reading lists and the purchases that result from them really help the bottom line during what can be a slow time. But with each purchase made for or by a lucky kid, there are many kids who cannot afford to buy the required reading.

Cline-Ransome astonishes with her sensitive portrayal of poverty, bullying, death, displacement, and loneliness; middle grade issues that resonate now as in 1946 when this story takes place. But what makes this slight book mighty is how she portrays poetry—the poetry of places and people—as both liberating and unifying, life-mirroring and lifesaving. The Great Migration, Chicago’s first public library named after an African American—George Cleveland Hall—and the Chicago Renaissance make up the historical background of Langston’s—named after his mother’s favorite poet—awakening. So much quiet, fierce, pride inhabits Cline-Ransome’s characters. The message: Poetry can save lives. So how about donating a poetry book to a public school library?

–Lucy Kogler, Lit Hub columnist

Javier Mariás, Between Eternities and Other Writings

(Vintage)

My first exposure to Javier Mariás’s work came through his nonfiction, including a regular column he wrote in the early days of The Believer. And while he’s best-known for his novels, including the likes of All Souls and Your Face Tomorrow, his nonfiction illuminates some of those same subjects in different ways. All of which is a very roundabout way of saying that Mariás has a new collection of nonfiction due out this month, Between Eternities and Other Writings, and I am very excited about it.

–Tobias Carroll, Lit Hub contributor

Laura van den Berg, The Third Hotel

(Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

This second novel from Find Me author van den Berg belongs on a shelf next to Pedro Páramo. Like Rulfo’s iconic 1955 novella, The Third Hotel is both a meditation on sorrow and longing—for answers, insight, closure—and a haunted and haunting quest narrative whose slimness belies an ocean of eerie power. It’s the story of a recently widowed sales rep who travels to Havana for a film festival after her horror film scholar husband, Richard, is killed in a hit-and-run. Upon arrival, she spots a man who looks exactly like Richard, and becomes obsessed with the notion that he has been resurrected. An utterly transfixing, dreamlike descent into the depths of a psyche stricken by grief and confusion, The Third Hotel is miniature marvel and the most unsettling book you’ll read all year.

–Dan Sheehan, Book Marks editor

Lea Carpenter, Red, White, Blue

(Knopf)

A spy novel for people who don’t like spy novels—namely me, who has been fully seduced by this diffuse, philosophical book. I suppose it’s about a woman grappling with life after the death of her father (a CIA agent), and also about the father himself, via his unnamed friend and colleague (the points of view alternate throughout). But more important to my reading experience are the meditations on alienation, on secrecy, and on manipulation, both as pertains to national security and matters rather closer to home. Challenging and often very beautiful, it’s a novel I’d recommend to anyone.

–Emily Temple, Lit Hub senior editor

Craig Brown, Ninety-Nine Glimpses of Princess Margaret

(Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

I’m not a Royalist, but there is something completely engrossing about Craig Brown’s Ninety-Nine Glimpses of Princess Margaret. Brown has written one of the most completist biographies I can think of in a very roundabout way: his Princess comes to life in formally inventive chapters—one chapter is comprised of public notices about HRH, another reveals more about her through her relationship with her personal driver, yet another casts a different sort of woman through her relationship to Picasso. All together, readers come to see more than just the bitchy, rude, quick-witted Margaret (although those are the best sections), but see her very privileged, very tragic life as well.

–Emily Firetog, Lit Hub managing editor