13 Literary Writers Who Have Adapted Other People’s Books for the Screen

Or: When Aldous Huxley Wrote Pride and Prejudice

Hollywood has long been a mysterious place where literary writers can sometimes make a little extra money—sure, there’s the nice paycheck when their own work gets optioned, but as it turns out, movies actually need writers too! And sometimes literary writers are pretty darn good at writing movies (though sometimes, as you will see, they are not). After discovering this week that Aldous Huxley had written the screenplays for early film adaptations of Pride and Prejudice and Jane Eyre, I got interested in what other literary texts (besides their own) literary writers had ushered towards the big screen. Here are some of my findings.

Aldous Huxley, most famous for his literature of dystopias and drug trips, wrote the screenplays for the first film adaptation of Pride and Prejudice (1940) and, with John Houseman and director Robert Stevenson, an early adaptation of Jane Eyre (1943). Not only that, but he might have been the screenwriter for Alice in Wonderland (this, of course, being quite a bit closer to the dystopia/drug trip fame). Knowing that Huxley was a massive fan of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Walt Disney contacted the writer in 1945 and commissioned a script for a combination live action and animated adaptation. He completed a draft, and the two icons worked on it together, but in the end Disney felt it was “too literary.” He was paid, and a wholly different and fully animated version (the one you know) was released in 1951.

Aldous Huxley, most famous for his literature of dystopias and drug trips, wrote the screenplays for the first film adaptation of Pride and Prejudice (1940) and, with John Houseman and director Robert Stevenson, an early adaptation of Jane Eyre (1943). Not only that, but he might have been the screenwriter for Alice in Wonderland (this, of course, being quite a bit closer to the dystopia/drug trip fame). Knowing that Huxley was a massive fan of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Walt Disney contacted the writer in 1945 and commissioned a script for a combination live action and animated adaptation. He completed a draft, and the two icons worked on it together, but in the end Disney felt it was “too literary.” He was paid, and a wholly different and fully animated version (the one you know) was released in 1951.

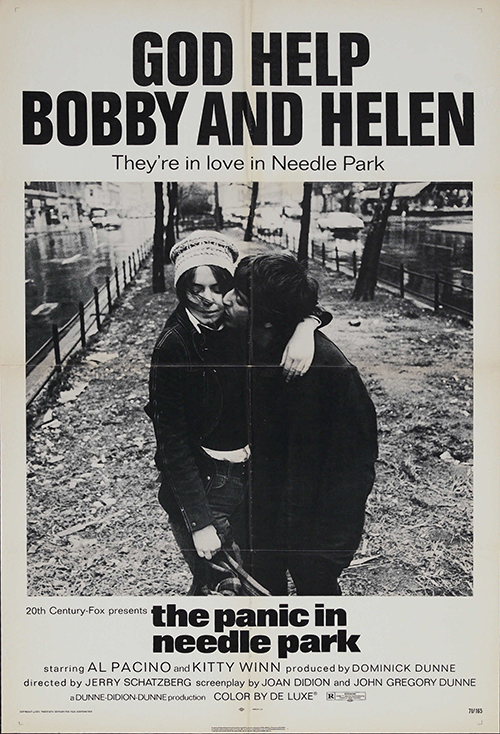

After the film rights for James Mills’s 1966 novel The Panic in Needle Park were purchased by producer Dominick Dunne, Dominick hired his brother, John Gregory Dunne, and his sister-in-law, Joan Didion, to write the screenplay (“a Dunne-Didion-Dunne production”!). The film premiered in 1971. Of Didion’s other screenplay credits, two more were based on other people’s books: she co-wrote the adaptation of her husband’s novel, True Confessions (1981), and adapted Alanna Nash’s biography of Jessica Savitch for Up Close and Personal (1996).

After the film rights for James Mills’s 1966 novel The Panic in Needle Park were purchased by producer Dominick Dunne, Dominick hired his brother, John Gregory Dunne, and his sister-in-law, Joan Didion, to write the screenplay (“a Dunne-Didion-Dunne production”!). The film premiered in 1971. Of Didion’s other screenplay credits, two more were based on other people’s books: she co-wrote the adaptation of her husband’s novel, True Confessions (1981), and adapted Alanna Nash’s biography of Jessica Savitch for Up Close and Personal (1996).

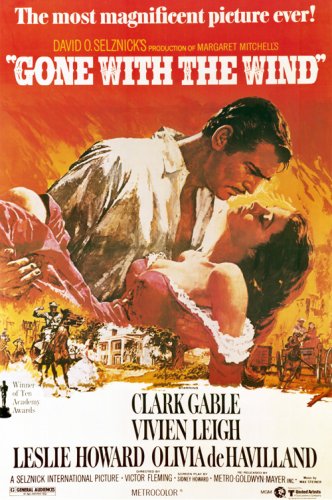

As you probably already know, F. Scott Fitzgerald toiled away to little success (one friend compared him to “a great sculptor who is hired to do a plumbing job”) in Hollywood in the 1930s, and wound up with only a single screenwriting credit. I was tickled to learn that he had worked on a draft of the script for the adaptation of Gone With the Wind, for which, apparently, “he was forbidden to use any words that did not appear in Margaret Mitchell’s text.” His draft was rejected.

As you probably already know, F. Scott Fitzgerald toiled away to little success (one friend compared him to “a great sculptor who is hired to do a plumbing job”) in Hollywood in the 1930s, and wound up with only a single screenwriting credit. I was tickled to learn that he had worked on a draft of the script for the adaptation of Gone With the Wind, for which, apparently, “he was forbidden to use any words that did not appear in Margaret Mitchell’s text.” His draft was rejected.

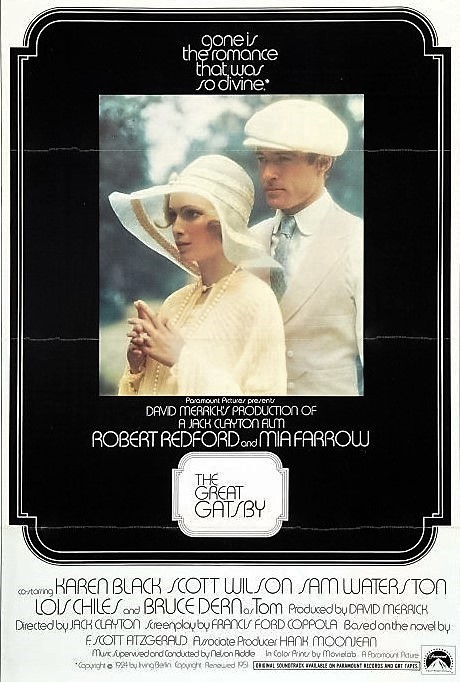

Truman Capote also wrote a rejected draft of a Great American Novel adaptation: The Great Gatsby, as luck would have it. Capote submitted it for Jack Clayton’s 1974 film adaptation. Baz Luhrmann described it like this:

Truman Capote also wrote a rejected draft of a Great American Novel adaptation: The Great Gatsby, as luck would have it. Capote submitted it for Jack Clayton’s 1974 film adaptation. Baz Luhrmann described it like this:

There’s a screenplay for it written by Truman Capote, which I got my hands on. Bob Evans, whom I now know very well and who was running the studio at the time, rejected it. Because, basically, Jordan is gay and Nick is gay and the script is too hardcore. Truman was really upset about it and went on television and called Paramount a bunch of wankers. It’s in his hand, but it’s totally legible. It’s also unfinished. Basically, it’s mad and bad and crazy.

Sounds great. You can read most of it here. Capote had also (with William Archibald) adapted Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw into a 1961 horror movie called The Innocents. Capote and Archibald won an Edgar Award in 1962 for Best Motion Picture Screenplay.

Famously, William Faulkner wrote the screenplay for the 1946 Warner Bros. adaptation of Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep—less famously, he co-wrote it with Leigh Brackett, cult pulp science fiction writer (otherwise known as the “Queen of Space Opera“) who also co-wrote The Empire Strikes Back, and the highly prolific screenwriter Jules Furthman. Faulkner, who after teaming up with director and producer Howard Hawks, worked in Hollywood for some twenty years (strictly to make money, of course), also wrote, among other things, the screenplay for the 1944 adaptation of Ernest Hemingway’s To Have and Have Not, and was an uncredited member of the writing team for the Academy Award-winning 1941 adaptation of James M. Cain’s Mildred Pierce.

Famously, William Faulkner wrote the screenplay for the 1946 Warner Bros. adaptation of Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep—less famously, he co-wrote it with Leigh Brackett, cult pulp science fiction writer (otherwise known as the “Queen of Space Opera“) who also co-wrote The Empire Strikes Back, and the highly prolific screenwriter Jules Furthman. Faulkner, who after teaming up with director and producer Howard Hawks, worked in Hollywood for some twenty years (strictly to make money, of course), also wrote, among other things, the screenplay for the 1944 adaptation of Ernest Hemingway’s To Have and Have Not, and was an uncredited member of the writing team for the Academy Award-winning 1941 adaptation of James M. Cain’s Mildred Pierce.

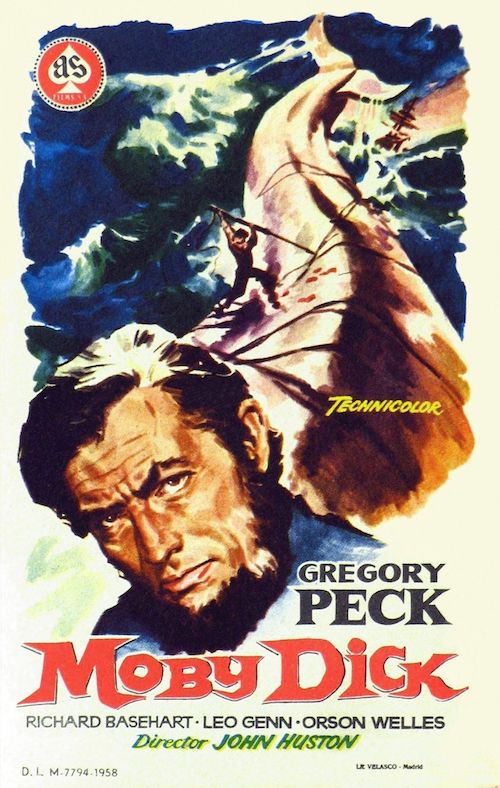

Greatest sci-fi writer in history Ray Bradbury wrote the screenplay for John Huston’s 1956 adaptation of Moby-Dick. “I had fallen in love with John Huston’s work when I was in my twenties,” he told The Paris Review in 2010. I’m just going to quote the rest in full, because it’s wonderful:

When I was twenty-nine I attended a film screening and John Huston was sitting right behind me. I wanted to turn, grab his hand, and say, I love you and I want to work with you. But I held off and waited until I had three books published, so I’d have proof of my love. I called my agent and said, Now I want to meet John Huston. We met on St. Valentine’s night, 1951, which is a great way to start a love affair. I said, Here are my books. If you like them, someday we must work together. A couple of years later, out of the blue, he called me up and said, Do you have some time to come to Europe and write Moby-Dick for the screen? I said, I don’t know, I’ve never been able to read the damn thing. So here I was confronted with a dilemma: Here’s a man that I love and whose work I admire. He’s offering me a job. Now, a lot of people would say, Grab it! Jesus, you like him, don’t ya? I said, Tell you what, I’ll go home tonight and I’ll read as much as I can, and I’ll come back for lunch tomorrow. By that time I will know how I feel about Melville. Because I’ve had copies of Moby-Dick around the house for years. So I went home and I read Moby-Dick. Strangely enough, a month earlier I’d been wandering around the house one night and picked up Moby-Dick and said to my wife, I wonder when I’m going to read this thing? So here I am sitting down to read it.

I dove into the middle of it instead of starting at the beginning. I came across a lot of beautiful poetry about the whiteness of the whale and the colors of nightmares and the great spirit’s spout. And I came upon a section toward the end where Ahab stands at the rail and says: “It is a mild, mild wind, and a mild looking sky; and the air smells now, as if it blew from a far-away meadow; they have been making hay somewhere under the slopes of the Andes, Starbuck, and the mowers are sleeping among the new-mown hay.” I turned back to the start: “Call me Ishmael.” I was in love! You fall in love with poetry. You fall in love with Shakespeare. I’d been in love with Shakespeare since I was fourteen. I was able to do the job not because I was in love with Melville, but because I was in love with Shakespeare. Shakespeare wrote Moby-Dick, using Melville as a Ouija board.

The day I went to see Huston I asked, Should I read up on the Freudians and Jungians and their interpretations of the white whale? He said, Hell no, I’m hiring Bradbury! Whatever is right or wrong about the screenplay will be yours, so we can at least say the skin around it is your skin.

So after I’d read the book multitudinous times, I wrote the beginning on the way to Europe on the boat, and that stayed. But everything else was so difficult. I had to borrow bits and pieces from late in the book and push them up front, because the novel is not constructed like a screenplay. It’s all over the place, a giant cannonade of impressions. And it’s a play too. Shakespearean asides, stage directions, everything.

I got out of the bed one morning in London, walked over to the mirror and said, I am Herman Melville. The ghost of Melville spoke to me and on that day I rewrote the last thirty pages of the screenplay. It all came out in one passionate explosion. I ran across London and took it to Huston. He said, My God, this is it.

When the interviewer points out that Bradbury changed the ending from Melville’s original, he says:

Yes, but it really works, because I came up with a revelation. To adapt for the screen you’ve got to decide what to throw overboard. I didn’t want Fedallah, the mysterious Parsi harpooner, because he’s a terrible bore and he’d turn the whole thing into comedy. He’s the extra mystical symbol that breaks the whale’s back. If you’re not careful in tragedy, one extra rape, one extra incest, one extra murder and it’s hoo-haw time all of a sudden. So I got rid of Fedallah, and that leaves us at the end with no one to go down with the whale. So, hell, it’s only natural that Moby Dick takes Ahab down with him and comes back up with all these harpoon lines, and Ahab gestures, so when the men follow him they are destroyed. Well, that’s not in the book. I’m sorry, but I’m proud of that. Awfully proud of that.

Bradbury’s 1992 novel Green Shadows, White Whale, is a fictionalized account of his experiences writing the screenplay with Huston in Ireland.

In addition to writing the screenplay for the 1971 adaptation (the only adaptation) of his own Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Roald Dahl, a close personal friend of Ian Fleming, wrote the screenplay for the 1967 adaptation of Fleming’s You Only Live Twice (though it should be said that this adaptation is extremely loose), and co-wrote the screenplay for the 1968 musical Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, based (also pretty loosely!) on Fleming’s 1964 novel Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang: The Magical Car. In non-Fleming related activities, Dahl also wrote the screenplay for the 1971 thriller The Night Digger, based on Joy Cowley’s novel Nest in a Fallen Tree, which starred his wife at the time, Patricia Neal.

In addition to writing the screenplay for the 1971 adaptation (the only adaptation) of his own Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Roald Dahl, a close personal friend of Ian Fleming, wrote the screenplay for the 1967 adaptation of Fleming’s You Only Live Twice (though it should be said that this adaptation is extremely loose), and co-wrote the screenplay for the 1968 musical Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, based (also pretty loosely!) on Fleming’s 1964 novel Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang: The Magical Car. In non-Fleming related activities, Dahl also wrote the screenplay for the 1971 thriller The Night Digger, based on Joy Cowley’s novel Nest in a Fallen Tree, which starred his wife at the time, Patricia Neal.

Nick Hornby is pretty much the modern master of this list. In addition to many novels, he has written the screenplays for the film adaptations of Colm Tóibín’s Brooklyn (Brooklyn, 2015), Cheryl Strayed’s Wild (Wild, 2014), Lyn Barber’s An Education (An Education, 2009), and the BBC television adaptation of Nina Sibbe’s Love, Nina: Despatches from Family Life (Love, Nina, 2016). “I started out trying to be some kind of scriptwriter,” Hornby said in a 2015 BAFTA lecture.

Nick Hornby is pretty much the modern master of this list. In addition to many novels, he has written the screenplays for the film adaptations of Colm Tóibín’s Brooklyn (Brooklyn, 2015), Cheryl Strayed’s Wild (Wild, 2014), Lyn Barber’s An Education (An Education, 2009), and the BBC television adaptation of Nina Sibbe’s Love, Nina: Despatches from Family Life (Love, Nina, 2016). “I started out trying to be some kind of scriptwriter,” Hornby said in a 2015 BAFTA lecture.

I didn’t think I could write prose, and so there was a sense of some unfinished business I think. I like writing dialogue very much and I love movies and TV. A friend of mine who’s an artist who I know through my children, I saw him one day and I said, “How was your day?” and he said, “Oh you know, genius wanker.” And I couldn’t believe that someone else understood the way that I spend my days.

And of course the genius part lasts for about five minutes, and the latter tends to last a lot longer in the course of the day. And there are two things with films that I think help with that. One is that, when you get to a certain point in your novelistic career, unless you really, really screw up badly, the book’s going to come out. And it’s just you, and you don’t particularly know how to judge it, and I guess the genius wanker thing then comes into overdrive. You’ll read a review that says you’re a genius and you’ll believe it, and then read one that says you’re the opposite and then believe that but for much longer.

But with a screenplay there are all these hurdles to jump over which seem to have some kind of objectivity to them. And of course films don’t always work out, but if you’ve written a screenplay that attracts the interest of a producer, and then attracts the interest of a cast and a director, and then finally and the biggest thing is some money to make the film, then you feel I think as if you’ve proved something—to yourself at least—by that point.

Nope, scratch that: Ruth Prawer Jhabvala is the master of this list. The Booker Prize-winning author (1975, for Heat and Dust) and 1984 MacArthur Fellow wrote a slew of screenplays for literary adaptations, and won two Academy Awards for her trouble: In 1987, for A Room With a View, and in 1992, for Howards End. That E.M. Forster fandom really paid off, is all I can say. She was also nominated for the same award in 1993, for her adaptation of Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day. Between 1979 and 2009, she also wrote screenplays adapting the following novels: Henry James’s The Europeans, The Bostonians, and The Golden Bowl, Jean Rhys’s Quartet, Bernice Rubens’s Madame Sousatzka, Evan S. Connell’s Mr. Bridge and Mrs. Bridge (as one film, Mr. and Mrs. Bridge), Kaylie Jones’s A Soldier’s Daughter Never Cries, Diane Johnson’s Le Divorce (co-written with James Ivory), and Peter Cameron’s The City of Your Final Destination. She also used Jane Austen’s version of Samuel Richardson’s Sir Charles Grandison as material for 1980’s Jane Austen in Manhattan, and adapted Arianna Huffington’s biography of Pablo Picasso into 1996’s Surviving Picasso. Whew.

Nope, scratch that: Ruth Prawer Jhabvala is the master of this list. The Booker Prize-winning author (1975, for Heat and Dust) and 1984 MacArthur Fellow wrote a slew of screenplays for literary adaptations, and won two Academy Awards for her trouble: In 1987, for A Room With a View, and in 1992, for Howards End. That E.M. Forster fandom really paid off, is all I can say. She was also nominated for the same award in 1993, for her adaptation of Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day. Between 1979 and 2009, she also wrote screenplays adapting the following novels: Henry James’s The Europeans, The Bostonians, and The Golden Bowl, Jean Rhys’s Quartet, Bernice Rubens’s Madame Sousatzka, Evan S. Connell’s Mr. Bridge and Mrs. Bridge (as one film, Mr. and Mrs. Bridge), Kaylie Jones’s A Soldier’s Daughter Never Cries, Diane Johnson’s Le Divorce (co-written with James Ivory), and Peter Cameron’s The City of Your Final Destination. She also used Jane Austen’s version of Samuel Richardson’s Sir Charles Grandison as material for 1980’s Jane Austen in Manhattan, and adapted Arianna Huffington’s biography of Pablo Picasso into 1996’s Surviving Picasso. Whew.

Obviously it had to be Larry McMurtry who co-wrote (with longtime writing partner Diana Ossana) the screenplay for the adaptation of Annie Proulx’s “Brokeback Mountain”—and won a Best Adapted Screenplay Oscar for it. It was Ossana who read the story in The New Yorker and sent it to McMurtry. He read it; they wrote to Proulx. She shrugged and the rest is history.

Obviously it had to be Larry McMurtry who co-wrote (with longtime writing partner Diana Ossana) the screenplay for the adaptation of Annie Proulx’s “Brokeback Mountain”—and won a Best Adapted Screenplay Oscar for it. It was Ossana who read the story in The New Yorker and sent it to McMurtry. He read it; they wrote to Proulx. She shrugged and the rest is history.

Dave Eggers co-wrote the screenplay for the 2009 film adaptation of Maurice Sendak’s beloved 338-word children’s book Where the Wild Things Are, along with director Spike Jonze. Many people found the movie to be . . . okay.

Dave Eggers co-wrote the screenplay for the 2009 film adaptation of Maurice Sendak’s beloved 338-word children’s book Where the Wild Things Are, along with director Spike Jonze. Many people found the movie to be . . . okay.