13 Adaptations Better Than the Books They’re Based On

(GASP)

Most of the time, when a beloved book is adapted into a film, or even into a television show, a form with a little more elbow room, shall we say, the magic doesn’t quite translate. Which isn’t to say the adaptations aren’t themselves good—it’s just that the books are usually better. Even very very good adaptations, like The Talented Mr. Ripley, can often only manage to be second fiddle to their source material.

But not always. Sometimes the movie really is better than the book. Below, the Lit Hub staff will argue the case for 13 adaptations which (in our humble/expert/individual opinions) manage to eclipse the books they’re based on. Add your own—or tell us why we’re wrong—in the comments.

Adaptation (2002)

dir. Spike Jonze

based on: The Orchid Thief by Susan Orlean (1998)

I saw Adaptation in the theater in 2002. I didn’t get it, and my high school boyfriend got mad at me because of that. But twenty years and several re-viewings later, I can now say that Spike Jonze’s film is not only the best adaptation of a book to the screen, it’s also (sorry, Susan) better than the book for all the ways it elevates the themes of the book without privileging the book over the movie.

Here’s the gist: “Charlie Kaufman,” played by Nicholas Cage, struggles to adapt Susan Orlean’s 1998 nonfiction book, The Orchid Thief, but he has writer’s block. Charlie’s twin brother Donald, also played by Nicholas Cage, wants to be a screenwriter too, even though he’s an idiot—but, in a cruel twist, he finds success just as Charlie’s depression spirals and failure seems inevitable. Charlie decides to visit Susan (Meryl Streep) in New York to talk about the script, but his social anxiety means Donald ends up taking his place. But Susan is evasive, acts strange, and, it turns out, is hiding a secret romance with John Laroche (Chris Cooper), the book’s subject. Absolute madcappery ensues—a spy trip to Florida, drugs, sex, shootings, and an alligator.

The book has none of that. Instead, the Laroche of Orlean’s New Yorker piece-turned-book is a horticulturalist who searches for a rare ghost orchid to clone to sell, and had hired Seminole natives in an attempt to circumvent laws that allowed people to remove endangered species from Florida swaps. It’s an exploration of obsession and passion, but there are no secret affairs or shoot outs.

In an interview with GQ, Orlean said of the movie:

[Reading the screenplay] was a complete shock. My first reaction was “Absolutely not!” They had to get my permission and I just said: “No! Are you kidding? This is going to ruin my career!” Very wisely, they didn’t really pressure me. They told me that everybody else had agreed and I somehow got emboldened. It was certainly scary to see the movie for the first time. It took a while for me to get over the idea that I had been insane to agree to it, but I love the movie now. What I admire the most is that it’s very true to the book’s themes of life and obsession, and there are also insights into things which are much more subtle in the book about longing, and about disappointment.

It’s a hysterical and bizarre movie, upsetting and strange. It reminds us that books are not movies and movies are not books, and to create one based on the other is to reimagine something that never existed in the first place. While The Orchid Thief is a work of nonfiction, the storytelling is dictated by Orlean’s calm and trusting voice. She reveals Laroche to us in such a way that we never truly believe his lies, but always his point of view. In the movie, there are so many layers of POV and truth (Kaufman vs. “Charlie” vs. “Donald” vs. Orlean!) that the idea of truth (non-fiction vs. reality vs. fantasy) is of little consequence.

–Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor

All the President’s Men (1976)

dir. Alan J. Pakula

based on: All the President’s Men by Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward (1974)

I’m not saying the book isn’t a classic: a genuinely important, history-shifting narrative that manages to weave together a wildly complex sequence of modern politics into a compelling, page-turning story. I’m just saying the movie is even better. William Goldman has told the story of turning the book into the movie, providing some nice juicy behind-the-scenes anecdotes about Redford, Bernstein, and co., while also giving a masterclass in screenplay craft and storytelling structure, so maybe I’m a bit biased in the film’s favor, but for me, seeing all that research, all those phone calls, all that typing (so much typing) brought to the screen in a way that somehow feels magical and larger-than-life is a trick few in the annals of adaptation have ever surpassed. Again, the book is more than respectable.

But how do you compete with Jason Robards throwing his feet up on the desk and taking a red pen to that copy, telling them they don’t have the story? Or with Hoffman drinking all those cups of coffee, frantically taking notes before he gets kicked out without finally getting that scoop he’s been after? Or just the sheer visual madness of the Post newsroom in those heady days? Director Alan J. Pakula had a knack for capturing odd slices of Americana and immortalizing them on the screen. (My God, we haven’t even discussed the overhead shot in the Library of Congress.) But for me it comes back to Goldman’s script, and the knack he had, perhaps better than any other modern screenwriter, for capturing the energy and the passion of a quest.

–Dwyer Murphy, CrimeReads Editor-in-Chief

The Handmaiden (2016)

dir. Park Chan-wook

based on: Fingersmith by Sarah Waters (2002)

Don’t get me wrong: I’m a fan of Sarah Waters’ Fingersmith, which is a sexy, twisty, and sumptuous novel set in Victorian England. I didn’t even know what I didn’t like about it until I saw Park Chan-wook’s equally sexy, twisty, and sumptuous reimagining, which transposes the action to 1930s colonial Korea—an impressive feat on its own. Appropriately (considering the themes at play here), it was only when The Handmaiden satisfied my secret wish that I even became aware of it.

Now is the time when I must warn: spoilers. OK? Onward:

Fingersmith starts as a classic double-cross story: in it, in part one, Sue, raised into the business of thievery by her adoptive mother Mrs. Sucksby, is recruited by a non-gentleman they call Gentleman to pose as a maid and convince a naïve but wealthy heiress to fall in love with him, at which point he will marry her, throw her in an insane asylum, and run off with her fortune, except for the portion that he’ll give to Sue. Easy enough—except Sue falls in love with the heiress, whose name is Maud. But she goes through with the plan anyway, only to find, when they arrive at the asylum, that it is she who is being shoved toward the doors—Gentleman and Maud have tricked her into taking Maud’s place.

In part two, we learn about Maud’s life, and how her uncle raised her to care for his collection of pornographic texts, and perform readings of them for his lascivious colleagues. We learn about her side of the plot—committing Sue in her place will allow her to escape her uncle and live freely—and that she has also fallen in love. But like Sue, she goes through with it anyway. Once the deed is done, Gentleman takes Maud to Mrs. Sucksby, who reveals that Sue is actually the noblewoman and Maud an orphan, switched at birth for Sue’s protection, and keeps Maud in her home as a prisoner, so that she and Gentleman might keep the fortune, which had been willed to both of the girls together. Until almost the very end, both Sue and Maud are brought low, betrayed by those they thought cared for them, ruined and hating one another.

The first part of The Handmaiden is very similar to the original plot of the novel. But in the second part, something else happens: instead of plunging forward despite their feelings, the two women find they cannot do so. Instead, they confess their plots to one another. And then they turn the tables—with the help of Mrs. Sucksby, no longer a villain. The class tension remains, but the baby swap twist is gone. Where Fingersmith unravels into a tragedy until the final pages, The Handmaiden spends its last third triumphant, joyous. (I’m reminded of the end of Inglourious Basterds.) Both horrible men are punished, our heroines are free (and rich), and they even manage to reclaim some of the tools of their oppression. You know, sexually! It was the ending that I didn’t know I always wanted from the novel, and I’m so glad I got to see it play out in such glorious fashion.

–Emily Temple, Managing Editor

The Maltese Falcon (1941)

dir. John Huston

based on: The Maltese Falcon by Dashiell Hammett (1930)

There’s really no need to read The Maltese Falcon, for the film captures everything good about the book and adds even more in terms of nuance and context. The dialogue from the novel makes its way near-verbatim into the film’s script, and the plot adheres faithfully enough, with cuts and changes for practical, rather than aesthetic, purposes. The 1931 pre-code adaptation is quite a bit more salacious, but the 1941 version tries as hard as it can to subtly code the more overt references to sex and sexuality from the novel and prior adaptation. The acting is impeccable, with career-defining turns from Humphrey Bogart, Peter Lorre, Sidney Greenstreet, and Mary Astor, and the craft behind the production shines in every detail, with John Huston’s direction keeping all the parts moving smoothly.

–Molly Odintz, CrimeReads Senior Editor

Station Eleven (2021-2022)

cr. Patrick Somerville

based on: Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel (2014)

In my two-plus years at Lit Hub, I’ve managed to avoid making any claim controversial enough to get me angry emails, but my time may have come. Let me start by saying the obvious: Emily St. John Mandel’s 2014 novel is very, very good. Readers loved the fresh idea of a “quiet apocalypse,” and also a hopeful one, in which Art is Still Valued (perhaps more so than today…?) and people mostly take care of each other. I read the book in 2014, and my memory of it is mostly vibes: longing and nostalgia, fear and unease, punctuated by moments of profundity.

HBO’s ten-episode series adaptation, led by Patrick Somerville (The Leftovers, Made for Love), while still plenty vibey, is grounded in incredibly human performances from its superb cast, whose stories are even more interconnected than in the book. I don’t want to say too much, but it’s clear from the trailers that Jeevan (Himesh Patel) and Kirsten (Mackenzie Davis), who only briefly interact at the beginning of the novel, become much more important to each other in the series. (We also see more of young Kirsten, played stunningly by child actor Matilda Lawler.) The Prophet, who is all Villain in the book, is given a more complex storyline, though Daniel Zovatto’s interpretation is still haunting as hell. Other characters—Clark (David Wilmot), Elizabeth (Caitlin FitzGerald), Miranda (Danielle Deadwyler), and the Conductor (Lori Petty)—ground the story as well.

Also, let’s be honest: I’m a sucker for melodrama. While the novel often feels artfully restrained, the series feels artfully liberated in its ability to provoke Big Feelings. Attribute it to the orchestral swells, the Shakespearean monologues, Mackenzie Davis’s expressive eyebrows. (The fact that we’ve been experiencing our own flu-like pandemic probably factors in as well.) As Sigrid Nunez wrote in her review of the novel for the New York Times Book Review, as much as she appreciated the book, “The hairs never rose on the back of [her] neck; [her] eyes never filled with tears.” (Which is fine! Arguably, that wasn’t St. John Mandel’s project.) However, when going into Station Eleven the series, expect the hair-raising and tears. (Or in my case, sobs.)

–Eliza Smith, Special Projects Editor

American Gods (2017-2021)

cr. Bryan Fuller and Michael Green

based on: American Gods by Neil Gaiman (2001)

Who am I to tell Neil effing Gaiman that the American Gods show was better than his book? Obviously no one, just a sharp-tongued, decaying lump of flesh whose arm is about to fall off. But what I’m arguing is that it’s a better experience taking in the cluttered American landscape of cranky gods—old and new—through Bryan Fuller and Michael Green’s minds than it is through my own while reading the original source material. For one, as vivid as Wednesday is in the book, my own imagination doesn’t come close to seeing Ian McShane’s combining the Gaiman outline with a bit of Deadwood’s Al Swearengen to make the ultimate amoral world builder and dad-god. He’s perfect. As Mr. Nancy tells Shadow (Ricky Whittle) when they take the psychedelic carousel ride, “We should have done this in my mind, not his.”

The TV adaptation also gives us a perfect circle of story between Mad Sweeney (Pablo Schreiber’s piskie/leprechaun) and Laura Moon (Emily Browning, whom Mad Sweeney calls “Dead Wife”; touching) that doesn’t exist in the book—a self-contained piece of poetic justice that doesn’t rely on the bigger, sprawling problem. Lastly, America works best in visuals—the shitty motels and cornfields and throwaways of Jesus trying to cross the Rio Grande—and the TV show translates that most easily, turning us all into disciples, however we’ve come to it. “Nobody’s American,” says Wednesday. “Not originally. That’s my point.” Also my point! The show is better, join me here.

–Janet Manley, Contributing Editor

A Simple Favor (2018)

dir. Paul Feig

based on: A Simple Favor by Darcey Bell (2017)

Even the author of A Simple Favor wasn’t expecting how incredibly charming this adaptation would turn out to be, as she wrote in a piece for CrimeReads. The folks behind the movie understood that preserving the humor of the original was key, and the two leads, Anna Kendrick and Blake Lively, brought attitude and chemistry. I don’t know if anyone has ever had more fun adapting a novel than the people involved in A Simple Favor.

–Molly Odintz, CrimeReads Senior Editor

Jaws (1975)

dir. Steven Spielberg

based on: Jaws by Peter Benchley (1974)

The movie Jaws is one of the greatest works of storytelling of all time. Everything that contributes to the development of the narrative (from Steven Spielberg’s direction to Peter Benchley and Carl Gottlieb’s screenplay to Verna Fields’s editing to John Williams’s music, etc) is absolutely perfect. It’s perfect. It has a flawless three-act structure, balanced character development and clear character motivation, a coterie of excellent minor villains and a believably omnipotent antagonist. While I am very glad that it won Oscars for Sound, Music, and Editing, I’m constantly very angry that it didn’t dominate the 1975 Oscars. It’s a perfect movie!

Right, anyway… Benchley’s original novel is a fascinating book, but it doesn’t have things straightened out the way the movie does. There’s too much going on—like Martin Brody’s history as a bad cop, Ellen Brody’s missing her NYC life, Matt Hooper’s hubris. Actually, everyone is such a mess that it’s hard to root for them, or care if they get eaten or not. But the movie Jaws is streamlined and efficient; it is in the creation of characters with clear personalities that incredibly complex, symbolic, analytically-rich situations can arise between them. You don’t need all the drama from the get-go—the shark coaxes out enough!

–Olivia Rutigliano, CrimeReads Associate Editor

The Leftovers (2014-2017)

cr. Damon Lindelof and Tom Perrotta

based on: The Leftovers by Tom Perrotta (2011)

The Leftovers is God-tier television, superior to all but a handful of other series, and there’s no shame in having your source material play second fiddle to what, I would argue, is one of the most significant artistic achievements of the 21st century. It’s probably an even easier pill to swallow if you co-created and steered the adaptation, as Perrotta did alongside Damon Lindelof in 2014. In fact, I can imagine few greater thrills for a novelist than being given the opportunity to reinhabit, and wildly expand through an entirely new medium, a fictional universe so recently pried away from you.

The Leftovers is set in upstate New York, then small town Texas, then southern Australia, in the years following the “Sudden Departure”—the inexplicable, simultaneous disappearance of 140 million people, or 2% of the world’s population—and focuses on police chief Kevin Garvey (a ripped and furrowed Justin Theroux) and his fractured family, grieving widow Nora Durst (Carrie Coon), and her disintegrating brother Reverend Matt Jamison (Christopher Eccleston) as they try to process their feelings and adjust to life in a what is, at least in an emotional sense, a post-apocalyptic world.

Across three wildly different seasons, The Leftovers is a protracted study of grief, “a phantasmagoric meditation on the terror inherent in having a family at all, not because you might lose them but because you almost certainly will,” as Emily Nussbaum so wonderfully encapsulated it ahead of the (perfect) series finale back in 2017, but it’s also just a really weird, really fun, really beautiful show, full of terrific performances (Coon’s in particular is a revelation), that defies classification at every turn. For the uninitiated, I would urge you not to be turned off by the admittedly dour pilot and instead (like the chain-smoking members of the Guilty Revenant cult) surrender yourself to what is, essentially, a trilogy of strange tragicomic novels brought vividly and tenderly to life.

–Dan Sheehan, Book Marks Editor-in-Chief

The Godfather (1972)

dir. Francis Ford Coppola

based on: The Godfather by Mario Puzo (1969)

Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather is one of the other greatest works of storytelling of all time, and, like Jaws, it’s another instance of a screenplay actually being a much-needed edit of the book. As was the case with Benchley and Gottlieb, Mario Puzo based his screenplay for The Godfather off his book, and Francis Ford Coppola took that and molded it, shaping Puzo’s ideas into the cinematic classic we have today. It’s one of the best examples of “adaptation” as a continuation, rather than a replacement, of the initial work.

–Olivia Rutigliano, CrimeReads Associate Editor

Cruising (1980)

dr. William Friedkin

based on: Cruising by Gerald Walker (1970)

To be honest I’ve only thumbed Gerald Walker’s 1970 novel in passing, more as a curiosity in an old paperback section of a used bookshop, a little surprised to realize that it was the source material for the 1980 fever dream written and directed by William Friedkin. My memories of that somewhat abbreviated reading experience are pretty hazy, but I remember finding it a fairly unremarkable crime story about a serial killer preying on the Manhattan gay leather scene, which of course is also what the movie is about…sort of. This is one of those cases where it’s pretty clear that the adaptation, in today’s speech, was an IP grab. Friedkin wanted to make a movie about a subculture, in particular the hard-core leather sub-culture in downtown Manhattan, and this was the material at hand.

So it probably shouldn’t be a surprise that the movie surpasses the book, though not without some contention. Cruising, starring Al Pacino as a young cop assigned to work his way into the world of gay S&M clubs in order to be bait for a serial killer who liked that look (that young Pacino look), stirred up a lot of debate in its day. The protests got in the way of production, and I’m sure modern viewers coming to the movie for the first time will still feel supremely uncomfortable about its sexual politics. But as an aesthetic achievement, it’s really quite breathtaking. The movement of the camera through the clubs, across the city, across the faces of young man after young man, each one of them exuding something quite different and wildly complex…there’s just nothing simple about Cruising. The psychological layers peel back one after another and what we’re left with is something raw and utterly human.

–Dwyer Murphy, CrimeReads Editor-in-Chief

Die Hard (1988)

dir. John McTiernan

based on: Nothing Lasts Forever by Roderick Thorp (1979)

First, let us note that Nothing Lasts Forever, Roderick Thorp’s 1979 novel that provided the blueprints for the first Die Hard movie, is good! It’s a great book. An introduction to the version I have describes its prequel, The Detective, as “the first serious claim in 20 years for the detective story as literature”; let’s not get too carried away about NLF, but it is, as a friend notes, a nice old piece of Christmas Eve lit.

Thorp’s action sequences are copied beat for beat in the film (“Geronimo, motherf*ckers”), but the setup is a little bit different: In the book, Joe Leland is a World War II veteran turned cop whose marriage failed, following which his wife died. He is headed to Los Angeles to see his daughter Steffie and her children at her company’s Christmas party, and the general feeling is a bit more depressing than the onscreen version which adds biceps and giant perms and Christmas lights to every scene possible. For Bruce Willis’ bloody singlet alone, we have to hand it to the movie.

The stakes—John McClane (Willis) getting that teddy bear to his wife and saving the marriage!—are much more spirited, and less nihilistic than the source material. Also, in the book, the chief villain is “Anton Gruber,” aka Little Tony; I can see the showrunners taking a pen out of their mouth with a diabolical smile and saying, “What if we called him Hans. Hans Gruber.” Improvements all around, no contest.

–Janet Manley, Contributing Editor

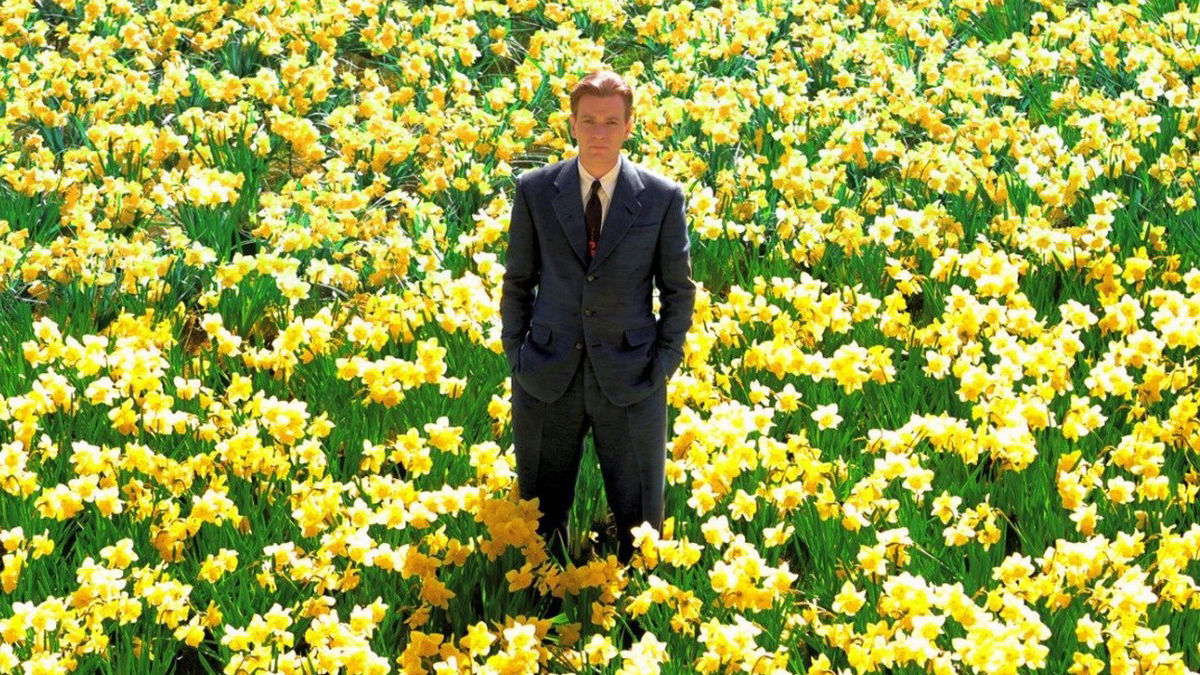

Big Fish (2003)

dir. Tim Burton

based on: Big Fish by Daniel Wallace (1998)

I love Tim Burton’s surreal picaresque-in-flashbacks Big Fish so much that it was going to be impossible for me to bring the same ardor to Daniel Wallace’s first-person novel of the same name. I think Burton’s Big Fish balances the relationship between the larger-than-life raconteur Edward Bloom and his now-grown son Will very well, because it allows them each equal objectivity. Wallace’s novel is told from the perspective of Will, remembering his father’s stories; everything is filtered through him, meaning we’re alienated from Edward’s perspective somewhat. Both the book and the movie interrogate Edward’s unreliability as a narrator, but we’re asked to evaluate that of Will in the book, too. Indeed, the novel places most of the focus on him, through his reflections on his father. But the film allows the audience to experience Edward’s spectacular adventures straight from the horse’s mouth.

–Olivia Rutigliano, CrimeReads Associate Editor

See also: LA Confidential, Fight Club, The Shining, Goodfellas, Thief, Friday Night Lights, The Magicians, etc.

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.